Anton Bruhin: One or Several Pipes?

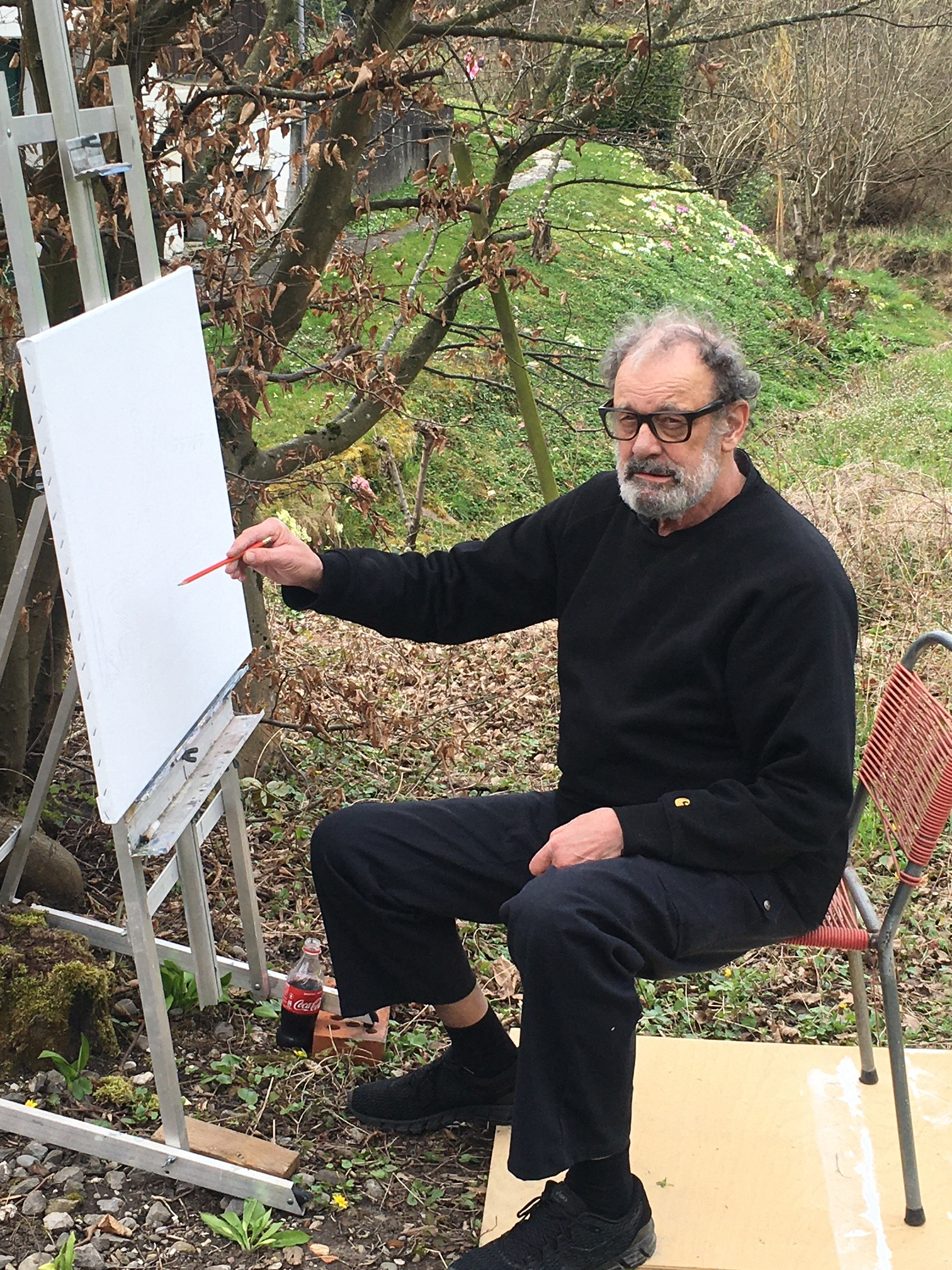

Anton Bruhin outside his studio in Zurich, 2020. Photo: Susi Koltai

Blank Forms

Brooklyn, NY 11238

While you’re here: Anton Bruhin has created an Art Edition riffing on his classic cat mosaic, Büsi für Blank Forms, published in conjunction with his exhibition One or Several Pipes?.

One or Several Pipes? is the first North American survey of Anton Bruhin (b.1949). The exhibition presents a comprehensive selection of the Swiss artist’s recent text art, sculpture, and drawings alongside key pieces dating back to the late sixties. At the root of Bruhin’s absurd and hallucinatory visions is his formalist approach to language: A childhood interest in typography led to early work in concrete and sound poetry, then fermented during his studies at the legendary experimental seminars Class F+F (Form und Farbe) at the Zürch Kunstgewerbeschule. Over time, Bruhin’s work became characterized by an economy of means, dry wit and wordplay, and an exploration of the hinterlands of communication.

The works featured in One or Several Pipes? draw on gestalt principles and post-painterly techniques, using materials ranging from enamel paints, typically used for lettering signs, to children’s LEGOs. Across these forms, Bruhin makes German-language palindromes, which take on the shape of signs referring back to their own illogical structure. At the center of Bruhin’s visual output is the ever present Suprematistischer Mickey, conceived in 1984 as an acrylic on canvas; it appears here in its original version and as a LEGO mosaic, Suprematistischer Mickey vor Sonnenuntergang. The work reconciles the ‘pure feeling’ of Kazimir Malevich’s black square with the mass commercialism of American pop culture, suggesting thawing Cold War tensions.

As we descend deeper into Bruhin’s universe, Malevich’s squares become wood blocks and pixels. In the nineties, Bruhin started experimenting with mosaic and sculpture, evoking a proto-digital world. His original Holzobjekt (wooden object) was styled as a monkey skull, inspired by Emmett Williams’s Out of Africa, a performance with an inflatable gorilla, which Williams staged multiple times in the 90s. Decades later, Holzobjekt variations proliferate as pareidolic totems; I’s become eyes and stairs become tongues, as Bruhin exhausts all possibilities of the design. Meanwhile, the series Hice for Weiss—a play on the irregular English conjugation of mouse to mice, here pluralizing ‘house’ as ‘hice’—collects over seven hundred 101 × 158 pixel drawings produced in Microsoft Paint (using a mouse!). Hice for Weiss, Bruhin’s second series to use the computer, builds his signature linguistic playfulness into a digital reprisal of his early ballpoint ink ‘stoner-drawings.’ Creating endless visions and variations on a theme via a reduced palette, Bruhin views restraint not as a limitation, but rather an opening for limitless creative potential. A relentless explorer of new forms, Bruhin himself put it best when he said: “Agriculturally speaking, I don’t produce monoculture.”

Anton Bruhin is an interdisciplinary artist based in Zurich, who emerged in the late 1970s and ‘80s alongside a generation of Swiss conceptual artists like David Weiss, Markus Raetz, and Jean-Frédéric Schnyder. In the mid-sixties, Bruhin attended Class F+F, an art and design course led by Serge Stauffer and Hansjörg Mattmüller at the Kunstgewerbeschule (now the Zurich University of the Arts), which became legendary after a clash between students and administrators led to the formation of the independent F+F Schule für Kunst und Design. During this time, Bruhin began producing performances such as Hungerstreik (for Joseph Beuys) and self-publishing books through April-Verlag. In 1968, Bruhin produced his ‘hippy-record,’ the album Vom Goldabfischer (Boing, 1970), a psychedelic folk freakout in which he played trümpi (more commonly known as the Jew’s harp) and homemade instruments alongside the guitarist Stephan Wittwer. It wasn’t long before Bernard Stollman, founder of the record label ESP-Disk, discovered Vom Goldabfischer, likely through Bruhin’s involvement with the Swiss counterculture magazine HOTCHA!. Stollman solicited a new record from Bruhin and Wittwer, but unfortunately, the label went bankrupt before the tapes arrived in New York. Still, Bruhin’s free-associative, nonsense lyrics would find analogues in his visual practice, notably his pen and ink drawings, and even his impending literary experiments.

In the seventies, when happenings and Fluxus performances were sweeping Europe, Bruhin was attending the guest lecture program at Kunstgewerbeschule. There he encountered German-language experimental poets like André Thomkins, a painter and author of German palindromes, and Anastasia Bitzos, an early compiler of sound poetry. Through Bitzos’s lectures, he also learned of Ernst Jandl’s reverse lipograms, poems where each word must contain a particular letter. These formal experiments with language would leave a lasting impression on Bruhin’s own work. Later in the ‘70s, he developed the sound poem Rotomotor, an ‘Idiotikon (vernacular dictionary) of the Swiss-German dialect.’ Rather than organize the words alphabetically, Bruhin ordered them by sound, setting the constraint that each word in the sequence must differ from its predecessor by just one letter—i.e., “fründ, gründ, grind, rind, find…” Originally written in Zurich in 1976, Rotomotor was performed several times and eventually published, alongside the material recorded for ESP-Disk, as Neun Improvisierte Stücke 1974/Rotomotor 1978 (Sunrise, 1978).

Bruhin’s first solo show, Kalligraphien, took place at Galerie Kornfeld in 1978; it featured a series of typographic glyphs done with pen and ink on paper, invoking Henri Michaux’s and Brion Gysin’s abstracted scripts. At the end of the decade, Bruhin’s early success culminated in a group show at Saus und Braus–Stadtkunst at the Strauhof Zürich, an exhibition of the urban youth movement, emerging visual art practices, and new wave music scene. Other notable contributors included Peter Fischli and David Weiss, presenting together for the first time, Urs Lüthi, and Klaudia Schifferle, bassist for the all-female punk rock band LiLiPUT.

During the eighties, Bruhin changed gears again to focus on plein air painting produced in Zurich, the Hungarian countryside, and New York, where he lived for brief stints during the decade. Bruhin’s embrace of the panoramic landscape recalled his earlier Landschaftsstenogramme, in which he attempted to document the landscape between Zurich and Carona via shorthand notation from the window of the train. He also produced portraits of friends and colleagues (including a well known one of Hans Krüsi) and a series of somber self-portraits.

Bruhin is perhaps best known outside of Switzerland as an experimental musician and poet, with an affection for the trümpi. Vom Goldabfischer first attracted the attention of record collectors when Nurse with Wound included it in the liner notes of their Chance Meeting on a Dissecting Table of a Sewing Machine and an Umbrella (United Dairies, 1979), the so-called ‘NWW List.’ However, the majority of Bruhin’s sonic experiments lay dormant until the nineties, when the Italian label Alga Marghen began a reissue campaign, starting with the CD InOut in 1996. Bruhin spent much of the decade performing his own music, participating in festivals across Europe and traveling to Japan to collaborate with avant-garde vocalist Makigami Koichi. He continued to show work in solo and group exhibitions in and around Zurich, and at the turn of the century, Bruhin’s visual practice went into overdrive, as the already prolific artist created endless morphological experiments with wooden sculptures and enamel-on-metal ‘paintings.’ Inspired by the question of how to use ever-fewer pixels to communicate an idea, Bruhin embarked on a series of mosaics using simple figures, alphabets, and optical tricks, eventually landing on the use of LEGO tiles, which has since become his hallmark style.

Bruhin is also a performer and anthologizer of Ländlermusik, the folk music of German-speaking Switzerland. He has compiled records dedicated to the Jew’s harp, such as Maultrommel, Mundharmonika, Kamm (Ex Libris, 1979), and illustrated trümpi performers, as in his series Ländlermusikanten, first shown in 1990 at Handsatz Fässler and later published as a book by Andreas Züst Verlag in 1999. That same year Iwan Schumacher produced the documentary film Trümpi: Anton Bruhin – The Jew’s Harp Player following Bruhin from Switzerland to Russia to Japan. The trümpi appears in much of his work, and in the late nineties, at the behest of Koichi, he created a series of drawings featuring the instrument, later published as Boing! (Woa Verlag, 1998).

Thanks to Susi Koltai, Emanuele Carcano, Tyler Maxin, Arthur Fink, and Brad Kronz for their support on this exhibition.

Blank Forms’s gallery space is located on the third floor of 468 Grand Ave in Clinton Hill. There is a step down from the street into the building and two flights of stairs—thirty-five in total, plus a hand rail—up to the gallery. If you require help accessing the space, please contact isaac@blankforms.org. Gallery hours: 12–6pm, Wednesday–Saturday.

For press inquiries, please contact press@blankforms.org.

Anton Bruhin: One or Several Pipes? is supported by the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia.

Blank Forms exhibitions are made possible by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature, and public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.