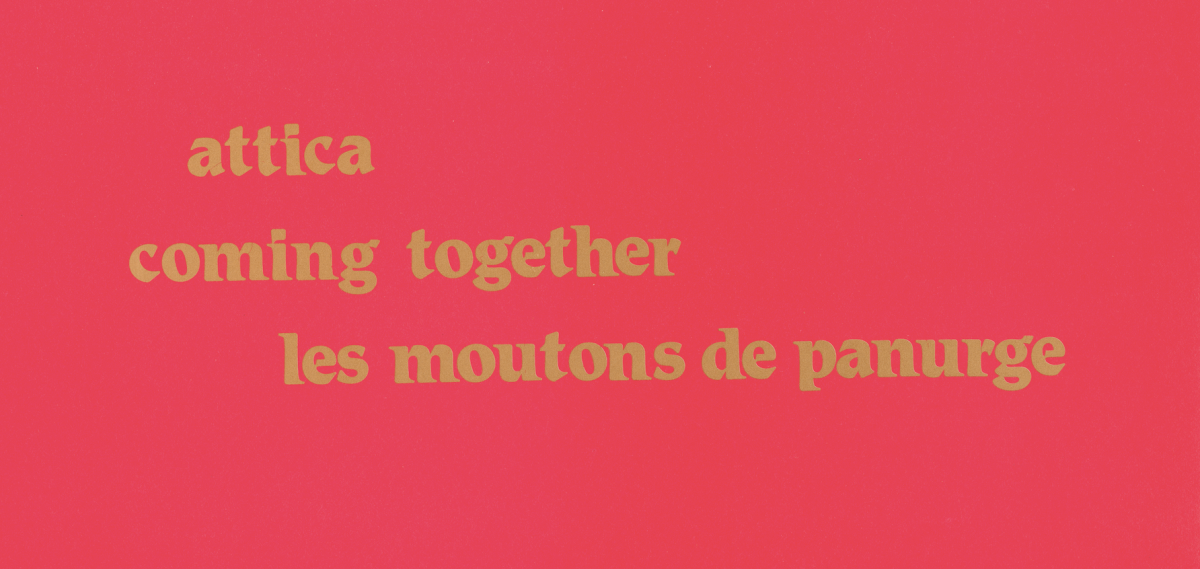

Untitled collage from Fighting Back! Attica Memorial to the People — 1974, published by Attica Brothers Legal Defense.

Fifty years on, Attica is still in front of us. Last September marked a half-century since the 1971 uprising at Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York; this January marked five decades since the composition of Frederic Rzewski’s catalytic responses, Attica and Coming Together, and the release of Archie Shepp’s landmark album Attica Blues (Impulse!). With these efforts, both composers sought to channel the energy of the rebellion, not only by responding to the events but politicizing musical form. Using the writing and voices of prisoners and movement figures Richard X Clark, William Kunstler, and Sam Melville, each aimed at overcoming the separation between advanced music and advanced action.

The seeds of the rebellion were planted during a strike at the Attica metal shop in July 29, 1970, which was followed soon after by a “spiritual sit-in” in observance of Black Solidarity Day. The administration promised the strikers amnesty for their protests but quickly sentenced them to long-term solitary confinement—the latest in a long line of broken promises. The next month, shortly after George Jackson was killed in California’s San Quentin State Prison, a small confrontation between a corrections officer and an inmate escalated into a riot, eventually becoming a full-scale take over of large sections of prison, including its central yard. Guards were taken hostage, demands were made, and negotiations initiated. For four days the eyes of the world were on Attica State as the prisoners addressed the nation and called for prominent politicians, journalists, and activists to visit the scene and participate as legal observers.

When New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller ordered the reconquest of Attica, C.O.s, state police, and national guards lined the battlements and rained bullets into the courtyard through a cloud of tear gas while blaring the message “surrender peacefully, you will not be harmed” over a loudspeaker. When the smoke cleared, thirty-nine people were dead.

New York State justified the massacre by alleging that prisoners had slashed the throats of hostages; the claim made headlines the following day and lingered despite being disproved by an autopsy. When the naked brutality of the troops against a group of hundreds of confined and substantially unarmed dissenters became apparent, the uprising drew immediate comparison to the Paris Commune, the centenary of which was celebrated earlier that year.

The rebellion agitated the Old Left and captivated the New. In addition to its avant-garde commemorations, popular musicians including Bob Dylan and John and Yoko Ono penned tributes. This collection of pieces looks at the cultural impact of the uprising, primarily on music but also visual art of the day, and on conditions in the present. It includes a radio show; a new translation of an essay based on a conversation between Shepp, lawyer William Kunstler, drummer Beaver Harris, and writer Val Wilmer; an interview with Joshua Melville, son of the murdered Attica Brother and Weatherman Sam Melville, whose letters about life in prison—detailing the "indifferent brutality, incessant noise, the experimental chemistry of food"—comprises the text of Rzewski's Coming Together; a contemporary poem by Jayne Cortez; a comparative essay by historicizing related works by Shepp, Rzewski, and Charles Mingus; and an art historical reflection the influence of prisons on Minimalism in the 1970s. These are accompanied by photographs that New York State sought to hide, which was eventually used as evidence in a successful, thirty-year long lawsuit to win a settlement for victims of the massacre and those survivors tortured by prison officials in the aftermath. These were secured by Elizabeth M. Fink, of the Attica Brothers Legal Defense, and graciously shared by filmmaker Michael Hull.