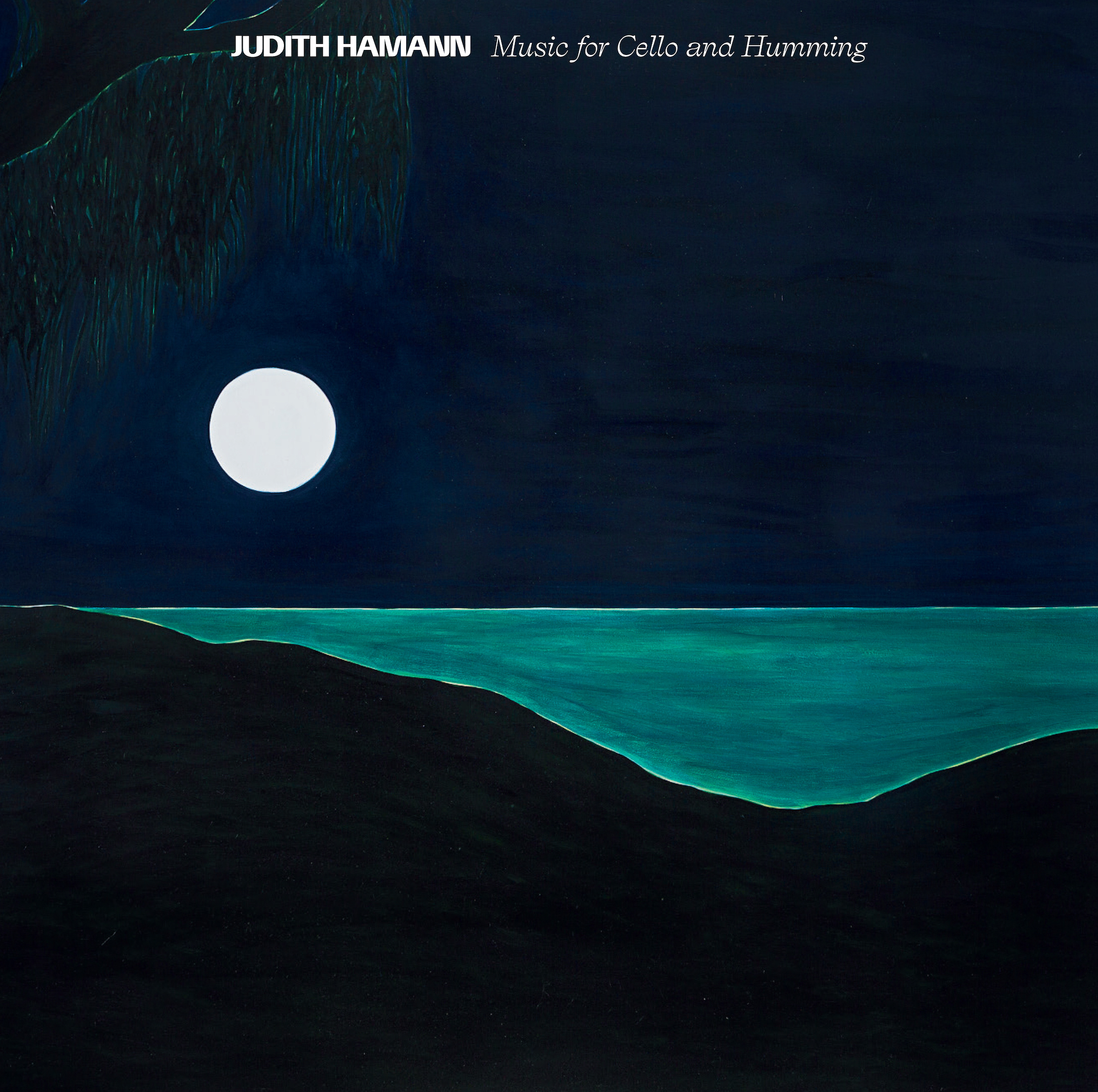

Judith Hamann, Music for Cello and Humming (Blank Forms Editions, 2020). Art by Patricia Leite, De longe, 2015, oil on wood, 55 × 63 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Mendes Wood DM São Paulo, Brussels, New York. Photo by Bruno Leão.

This conversation took place via Skype between Sarah Hennies in Ithaca, New York, and Judith Hamann in Suomenlinna, Finland, on March 11, 2020. Previously unpublished, the transcript has been edited for clarity. Hamann performs Hennies's 2018 composition "Loss" on Music for Cello and Humming (Blank Forms Editions, 2020)

SARAH HENNIES: We’re having this conversation because you asked me for a piece that I then wrote for you, and we like each other.

JUDITH HAMANN: And I really liked the piece. I’m really glad that you wrote me that piece.

SH: Yeah, it’s been stuck in my memory. I wrote a lot of music over the last couple of years, and that piece in particular was really easy to write for some reason. I don’t know if I had an idea for it—it just came quickly, and then it was done, and then has stayed as one of my favorite things I’ve done in the last couple of years.

JH: I remember when you wrote it—I sent you these humming ideas, sketches I’d been trying out, and you were like, “OK, no worries, I can work with this.” And then, I don’t know, two weeks later, maybe less, you sent over the piece: “OK, so this was easy.”

SH: That’s my patented move. Someone’s like, “Can you write me a piece?” And then two days later it’s like, “Yeah, here it is.” I don’t know if I’m capable of that anymore. My friend Bill Baird is a songwriter who produced something like eight albums in two years, and he called it “the great unclogging.”

JH: Maybe this piece was part of the great unclogging for you.

SH: The floodgates were opening or something.

JH: All those pent-up compositional tendencies.

SH: Right. I really like doing tasks where there is something more specific than just, “Give me a cello piece.” For some reason, you asking me for the humming piece was just enough of a thing for me to say, “Oh, OK, I can do this.” I don’t know why that is exactly, but because of the humming, I had the idea that the player in this piece has a hidden speaker playing back a track of sine waves. So the piece is a sort of trio between voice, cello, and sine wave. The idea of you humming made me think of having this third voice, and the piece was really easy to write after that. It happened really intuitively.

JH: I think there’s some kind of relationship between the hidden speaker and the humming because humming itself is also quite hidden in a way. I think it’s very unclear what is what—what the overall sound is made up of, at least until the voices start to peel apart and start manifesting in three-part harmony. At the beginning, there’s a question of whether the interference is coming from the humming. Is it coming from the sine tone? It’s not a visibly registrable thing, to hum—you’re not moving your mouth, it’s very subtle. I keep thinking about humming in general, particularly combined with the cello, as being something like a form of ventriloquism.

SH: Yeah, I was just about to say that: because your mouth is closed and it’s coming out of your nose, it has a disembodied quality, which I think is how it relates in my head to having a speaker with the sine wave. It’s not that I was trying to trick people, but you really don’t hear that there are three voices until much later in the piece, and then it becomes obvious. I really like string and percussion instruments, and piano specifically, because you can see what’s happening. I had to write a trumpet piece recently for Nate Wooley, and I was out of my mind, like, I don’t know what to do with this instrument. I have a really hard time with it. I can’t write for this instrument because it doesn’t have anything to do with touch. I understand touch and sight. It created some friction, but by you asking me for humming—“Give me a piece for humming cellist”—I had to decide: Why would I ever do that? I really like it when people ask me to do stuff like that.

JH: If someone said, “Write me a cello piece,” you wouldn’t have thought: “Humming, huh?”

SH: Well, as it is, I happen to be finishing a different cello piece right now that has been much more difficult for me to write, partially because there were no restrictions other than duration. It was just, “Give me a cello piece.” And, well, that could be anything. So the presence of the second “instrument” guides that a little bit.

JH: It’s been interesting when I’ve performed it. Often people “get it” later. Often, it’s only after the piece that people ask or understand that there was an electronics part. I think there’s a really interesting, weird kind of composite that happens psychoacoustically between the cello and the humming that’s disorienting enough, such that whether there is a third element is unclear in certain ways.

SH: Right. And I hope that it reveals itself in the piece. Like I said, the idea wasn’t to have the sine waves be a secret, concealed, magical voice, but rather that it becomes clear later in the piece. At one point, it plays a tone that’s so high that it couldn’t possibly be produced by voice and cello. At some point, you start to hear tones that are very obviously electronic.

JH: Also, there are obvious moments when it’s on its own and so clear, and my hum is so unstable—

SH: Compared to a sine wave, yeah.

JH: Speaking generally, this has been such an interest- ing challenge for me, mostly in terms of trying to get from the start to the finish without clearing my throat—that’s a really intense thing.

SH: Oh yeah. I hadn’t even thought of that . . . because the piece is half an hour long.

JH: And I feel like if I clear my throat because of the coughing . . .

SH: Now it feels cruel. But for people who don’t know the piece, there’s a part where the cellist is instructed to cough in the middle of the piece, which apparently baffled some European concertgoers. I hadn’t thought of that at all because it’s this moment of theater, with coughing, that if you were to cough “for real” it would totally change that.

JH: Exactly. So then people would just think, Judith’s coughing again, ruining the piece! It’s interesting compositionally, but it’s also interesting physically. I feel like it’s such a rupture when the coughing happens. The whole first half of the piece starts in this specific place that, for certain listeners or, for instance, for these European concertgoers who were so baffled by the cough, is reasonably familiar in terms of harmonic and psychoacoustic activity. It starts in a place where the material is not neces- sarily unfamiliar, and it’s very beautiful. And then comes this descent, this breaking apart into more and more rupture of that “beautiful” structure. I love how uncomfortable it becomes. The coughing then becomes this magical thing, in terms of form. But also it does something physically to me as a performer: after the coughing, when I have to wait for a minute and a half of silence and then hum again, the coughing means that the last humming section is so volatile and breakable and fucked up by the time I get there. Whether or not that was intentional, I think it does something—it damages the “instrument” of the hum in a way that’s really interesting.

SH: Yeah. I actually didn’t realize that about the physical ability needed to play the piece, but that was totally by design. I always think about when I saw the movie Psycho (1960) in a theater several years ago and was reading the film notes, and it talks about how the shower scene in Psycho was one of the first, or maybe the first, really famous example of a film where you’re watching one film, and then the main character gets killed and all of a sudden everything is different. A rupture of audience expectation, everyone in the room experiencing this thing that they didn’t think would happen, in the context of that having never happened in a film before. Who kills the main character of their film? It’s crazy. So I like putting these things into pieces that leave the audience wondering what could happen to them.

JH: Investing in a character is sort of like investing in musical material in a way. You settle people, an audience, into this space where there is an under- standing or an agreement that this is the musical space in which this piece is going to happen. In “Loss,” the character in the narrative and the material and the function of the material completely change.

SH: Right? And I feel like that is analogous to something that happens in life that people, for whatever reason, don’t seem to expect in a piece of music: that something could happen to you actually, in real life, where all of a sudden your entire life is different. I’m really interested in the kind of rupture of experience and expectation that causes this. I think the first time I did this was a solo snare drum piece called “Cast and Work” (2013), where there are hidden offstage musicians around the room, and it’s a single, continuous twenty-three-minute drum- roll along with these three sine waves that slowly fade in over time. It’s hypnotic and physically really tough to play because it’s a continuous roll for twenty-three minutes—but fifteen minutes into the piece, there’s this explosion of horrible string noise. [Laughs] It just begins, and it continues for five minutes, and then it ends, and it never happens again. I really like what that does to people—it causes all these different things to happen experientially that I’m interested in. One of them, like I said, is this sense of, what else could happen to me? Could this happen again? But also, someone told me they heard it as a kind of release. The piece was so intensely focused that they felt it. They were able to breathe once that happened, which made me like it even more because then it has this double function of something seemingly being horrible but at the same time giving you some relief. That kind of friction seemed to exist also between what we were talking about with the voice and the sine wave and the cello.

JH: I guess it’s also like a release from this space that’s being constructed for you; you expect you’re just going to have to spend half an hour in the space. People think for the first section, “Oh, it’s a half- hour-long piece,” and it’s this material, and it’s this structure: “I get it.” And so I’m just going to sit very quietly and hold my breath, and all those kinds of behavior, which are very . . . reverent in a way. I’m often thinking about these things in terms of performance specifically, and not so much about how people would listen to these pieces as recording . . . but then it all completely dissolves and changes. I like that. It’s just like—what? What could happen now that this has?

SH: Yeah. Because you think you’re listening to a quiet, droney psychoacoustic piece, and then all of a sudden, you’re not. I don’t mean this in a sadistic way, but I hope it is upsetting in some way for people. At least that’s the gesture . . .

JH: I think some people do find this a slightly “upset- ting” piece, not in terms of trauma or anything like that, but it’s disconcerting, uncomfortable. That’s one of the things I like about the piece—it’s very personal, not just in its composed or performed material but in the way people respond to it.

SH: Yeah. I don’t know why that is the thing that comes naturally to me, that this is the piece that felt natural and easy to write. I don’t want to delve too deeply into that in this conversation necessarily, but just personally, as a question for myself: Why is this the thing that occurred when someone said, “Write me a piece for humming cellists”? That was the only instruction, but I guess it was just enough to spur on my writing the piece, or it had just enough to do with other things that I’m naturally preoccupied with that it worked really well . . .

JH: I remember when we were initially talking about the piece, and you asked, “So, what’s your humming range?” I said, “From G to G,” and you immediately responded, “Great!” And then, in the piece itself, there are pitches at least a fourth outside of that! I don’t think we even talked about it at the time, but that translated to me instantly as setting up a parameter or a setting for both struggle and potential failure.

SH: I would say guaranteed failure.

JH: Initially, I thought, “I’m never going to be able to hum those Cs.” But strangely, some of the time it works, which has been interesting in itself. That’s something that’s been interesting and also reward- ing for me with this piece. It gels so much with a lot of stuff that I was thinking about and also reading when you wrote me a piece: about failure as generative material. At the time, I was also finishing my doctoral dissertation, and a lot of what I was thinking about there was in terms of creating a compositional setting where there are uncontrolled, non-intentional artifacts and phenomena arising from the process of navigating the piece, but those byproducts become the focal material, or the guide, the “score” even, in a way . . . “Loss” feels related to those ideas—like establishing a parameter, a setting, where my voice definitely would crack, where I would definitely not quite hit that note, where my voice would waver. All those are things that aren’t contained within the score overtly at all, but they’re in some ways the most important. The focal material here is breakable, and it’s human, and it’s not actually going to work. Some of the most interesting and beautiful stuff that happens is because that’s been set in motion.

SH: Yeah. That definitely is a tendency of mine, to ask, “What can you do?” And then ask them to do just a little bit more. Someone characterized it once as the sound of effort. I made this vocal piece with sine waves probably ten years ago that wound up as part of the soundtrack of my piece Contralto (2017), where it’s just a drone piece. It’s four voices, all done by me across my possible vocal range, from low to pretty high because I have a somewhat higher but assigned-male-at-birth voice, you know? So I have a falsetto range—and it’s this really beautiful piece where all it is is just humming, the sound of humming and inhaling, along with sine waves tuned to the same pitches. I guess it ties into what you were saying earlier about how your hum is unstable compared to the sine wave. That was the piece that I wanted to make, except that was the only thing happening in the piece. I set the highest tone at a note that I could just barely sing—or barely hum, I should say. Actually, I don’t know if I was thinking about that piece when I wrote your piece or not. But it definitely was in my memory, because it now is immortalized in this film that I made. The chord that I chose is really pretty. It’s not a major chord, but it’s very consonant. It’s not dissonant. Because the highest voice is struggling to sing the pitch that the sine wave is producing, it gives it just the tiniest amount of friction that I really like. I don’t know if subversive is the right word, but it’s subtly upsetting. This is a recurring thing with me—that you can never quite have the thing that you want. I don’t mean that as a fault, but it makes the music more interesting to me. I think this is why I don’t get into people like Christian Fennesz or Tim Hecker. There’s no friction in that music. It’s too—

JH: Like it’s too perfect, too consistent—

SH: It’s too consistently satisfying or something—yeah, there is no friction. Which isn’t to say that there’s anything wrong with that music, it’s just not my taste. If I were to have made that droning humming piece and set the highest pitch a little bit lower, I think it would be a less interesting piece—I guess that’s what I’m trying to say.

JH: Yeah, the struggle, this sort of strain, or the effort— and coming back to the idea of your work being an exercise in effort is part of . . . I was going to say the theater of it, but I don’t want to think of it as drama because I don’t think it’s dramatic or theatrical at all. I think, instead, it’s more like attempting a task that is just beyond your reach, and then what happens when you partially make it and partially fail at the task—that’s right where the interesting stuff happens, that’s where all that friction is.

SH: Yeah, and you’re not supposed to fail in chamber music or classical music, period. That’s the whole basis of instrumental instruction in academic music—to learn it perfectly.

JH: And to perform it perfectly, too. l think that raises a lot of interesting questions in terms of what a good or successful performance of a piece might look like when the work is built around struggle and the potential for failure—the certainty of failure even! I’m sure if I were a different person who was interested in different things, I’d have thought, “Well, I’ll have to get some vocal coaching to really nail that.” But that wasn’t what was interesting to me at all.

SH: I worked with a percussionist who asked me for a piece where I wrote him an extremely impossible piece. Like, absurdly not playable. This person was, or is, very concerned with what he calls accuracy—and it absolutely broke him. He came to my house to record it, and he was befuddled and showing me the score. He asked me, “How would you play this? This isn’t possible, right?” And I said, “Well, I wouldn’t play it . . .

JH: “That’s why I wrote it for you!”

SH: He could not process what I was saying when I said a correct performance is one where you do not play what is written. He kept saying, “Yeah, but the notes, the score!” And I had to say, “No. ‘Perfect’ is not the piece.” It asks the percussionist to play four different tempos with both hands and feet at the same time while also having to throw objects into a bucket that is sitting on the floor across the room. I mean, it’s stupid— stupidly—not easy. Not even not easy. Literally not playable. I think that’s the point—but I will say he did play it really, really well. You’ve learned it as well as one could have learned this impossible piece. That’s all just to say that I’m agreeing with you, that I don’t think you getting a vocal coach was in the spirit of this piece.

JH: No, not at all . . . I guess I play less and less music written by other people these days; the music that I do play by other people, I feel all have this common ground of some integral aspect of the piece unfold- ing in artifacts, accidents, effort, byproducts . . . I think, in a lot of classical music pedagogy that I moved through, the score is an arbiter of precision or accuracy that must be obeyed as perfectly as possible. The performer or the interpreter is just a poor, flawed, human being who needs to become invisible or transparent in a way. That’s a hang- over from Modernism, I guess—from people like Schoenberg, or even Adorno. But as an “Australian,” it feels very tied to colonialism as well, in a way, systems of domination or control. These days, I’m not really interested in performing that kind of music anymore, not because of the music itself, so much of which is amazing, but because of that whole apparatus around it. I think this piece and other pieces that I am interested in playing—in terms of notated music that’s written by someone else—they all in some way destabilize or undo those things that are from a conservatory-training background. They’re focused on what you’re not meant to do or prioritize.

SH: Yeah.

JH: There’s so much richness in that territory. Don’t get me wrong: I love being an interpreter, and I love the process of learning a piece and working it into your body and all the decision-making processes and frameworks around that. And I love working with other people on music. So it’s not that I want to stop and only do my own thing. But I find that the specific composers I’m mostly working with these days, or the people that I collaborate with—it’s a completely different kind of space to be a performer or interpreter. It’s a different set of relationships.

SH: Because you’re not following my law, you’re just doing what you can.

JH: It was interesting. I think I was reading The Queer Art of Failure [Jack Halberstam, Duke University Press, 2011] for the first time around when you wrote me the piece. Maybe that’s why I thought, “A fourth outside my vocal range. Perfect.”

SH: I used to tell this story before performances of my solo piece Falsetto (2016), which is another impossible-to-play piece of performance art. When I was a student, I read this interview— or, it was a transcription of a panel discussion with [Iannis] Xenakis, where I think he was present for a festival of his music, and one of the piano parts on one of his pieces had been given to be played by a Disklavier instead of a human. During the Q&A, someone asked him how he felt about that. He said he felt fine about it. And they said, “Well, I saw in this part that there are things in this part that are impossible. They can’t be played.” And Xenakis said, “Yeah, that’s true.” And, the guy, in a very typical music school way, asked, “As performers, what are we supposed to do with that? If we have you, a composer, giving us something that you know ahead of time is impossible . . . ?” And he said that he wanted people to play with a sorrow of knowing that they couldn’t do everything.

JH: There are all these different ways that people can approach the idea of the impossible in music. I love that, and I think that Xenakis talking about sorrow is very different from the kind of masochism you end up engaging in with some New Complexity composers, for instance.

SH: Because you’re supposed to play that stuff right. That’s the macho gesture of playing [Brian] Ferneyhough: “Look, I played all the right notes.”

JH: “I climbed the impossible mountain.” It’s like extreme sports for playing notes.

SH: This is why I love Xenakis. I love Xenakis for lots of reasons, including that he does write incredibly complex music. I had a teacher in undergrad who always harped about how practical Xenakis was, which sounds crazy at first, and then the more you read about him and look at his scores, he makes complex music, but it is actually really practical.

JH: It’s practical, and it’s also musical.

SH: It was so refreshing to hear Xenakis, a composer of loud, aggressive chamber music, say that [about playing impossible scores] because you know, you’d never hear Brian Ferneyhough say that.

JH: No, he’s not going to talk about sorrow and musical performance . . . I don’t think.

SH: No. The whole thing is like, “Can you believe that I wrote this thing for you that is so complicated?” I don’t know. I don’t need to rag on Brian Ferneyhough.

JH: Yeah. I’ve had to play some in my time as well, and it’s kind of a muscular, flexing, dude culture. Of course, in cello repertoire, you have [Ferneyhough’s] “Time and Motion Study II” (1977), which is a statement to perform. It’s a conquering gesture, an exertion of dominance, maybe. “Yeah, I did Time and Motion!” [Xenakis’s] “Nomos Alpha” [1966], of course, has all this impossible stuff in it, but it somehow makes sense. There are things that you can’t physically do, and you have to make a choice, but then it’s also beautiful and gestural in the way it sits in your body, so even though it’s really hard, it doesn’t feel like an imposition of will over the instrument. It feels like, “OK, I just have to live within this for a while.”

SH: You know, his percussion music is like that too, in that—as someone who hates loud, drummy percussion music—it seems like something that I would hate, but is amazing for all of the reasons that you just said. It’s so physical and immediate, but also full of life, and not from a place of virtuosity.

JH: Or, like, machismo, or a lot of the other reasons why things are loud or complicated.

SH: Yeah.

JH: Oh, Xenakis. We love Xenakis.

SH: We love Xenakis . . .

JH: I wanted to ask about how, whenever I’m talking to other people about this piece or describing it, going back to speaker and cello, or the sine wave, humming, and cello together, I always end up using the word composite. Even when things start to split off, when the cello becomes more rhythmic and percussive, my way of approaching everything as the performer is that it’s still one overall sound, one composite, rather than different timbres or textures, even when it becomes quite different.

SH: I feel that way, too. I don’t know if that’s in the writing necessarily, but I feel like I’m a very monophonic musician.

JH: Maybe that’s the word that I’m missing? Even though there are three voices, it doesn’t feel like three discrete voices, or that there’s one foregrounded and the others are background. Yeah, perhaps that’s the term: a monophonic sound that’s the sum of everything together.

SH: I would never call it a trio—I would only describe this piece as a solo. I would definitely not describe it as three voices, even though there are three distinct voices. This is something that I’ve thought about a lot, but I don’t have a lot of insight into. I played a lot of music in college by Stuart Saunders Smith, who writes very contrapuntal, sort of post-jazz chamber music. It doesn’t “sound like jazz” necessarily—it’s rhythmically complex but conceptually somewhat conventional music.

JH: Yeah, I'm familiar with his music.

SH: I had played this vibraphone piece of his called “Links No. 10 (Who are we? Where are we?)” (1993). It’s a series of eleven pieces for vibraphone. I had learned that piece up and down, and I was playing what I thought was a really great performance, and when he heard it, he said, “This is a melody with accompaniment, and you should play it that way.” To this day, I still cannot hear his music as melody with accompaniment. I can only hear it as a composite thing, as a single mass. And this isn’t about how the piece is written. I can see what he means by melody and accompaniment on the page, but I find it impossible to play it that way. I think this is true of almost everything I’ve written—that even when there are multiple instruments, what’s happening is like a single mass of some kind. . . . A better way to put it is that it’s like it has a singular purpose or something that I hear all together instead of as a bunch of stuff happening at once.

JH: I think that’s really interesting, that makes sense.

SH: I don’t know why that is. I think it has something in common with the weird block I have with learning tonal music. When I was younger, as a percussionist, I could learn atonal music almost effortlessly. But I still find playing in a key signature really hard. It’s really strange—and I don’t mind ’cause I don’t play tonal music. I have always remembered this experience when, in my second year of undergrad, I got a new percussion teacher because the previous one retired, and he was evaluating everyone’s skills. He had me sight-read a tonal melody, which I played horribly. Then he put an atonal melody in front of me, and I played it perfectly. And he said, “Huh, that’s weird.” Because prior to that, I think he just thought that I was not a good player, but I just don’t process tonal music in the way that you’re supposed to or something. I think this is completely tied to this idea of only hearing things as a singularity. Or, maybe a better way to put it is as a “total experience.”

JH: What’s the quote? What is that quote [“total experience”] from?

SH: I couldn’t tell you.

JH: Just a general, total experience.

SH: Like a roller coaster.

JH: It’s all the ups and the downs and the screaming . . . they’re all part of the same thing.

SH: I mean, I feel that way.