Don Cherry in the Alps, 1975. Photo: Moki Cherry.

I wanted to play different instruments in environments not man-made for music–natural settings like a catacomb or on a mountaintop or by the side of a lake. I wasn’t playing for jazz audiences then, you realize. I was playing for goat herders who would take out their flutes and join me and for anyone else who wanted to listen or to sing and play along. It was the whole idea of organic music—music as a natural part of your day. 1

—Don Cherry

Organic Music Theatre was a collaborative intermedia initiative of the American musician Don Cherry and the Swedish artist Moki Cherry. Their idealistic vision came together in the early 1970s against a backdrop of intense division and conflict in the United States. Though Don had distanced himself from most overt political actions, believing music itself should not be political, his collaborative work with Moki cannot be separated from the larger social context in which it was made. “These days politics just slaps you in the face. As a Negro raised in a mixed neighborhood, white people put me down, and black people put the white people down. I soon discovered hate–and I soon learned that we have to fight hate.” 2 Appalled by the US bombing of Cambodia as well as the state of race relations in America, the couple left the country in the spring of 1970 and by the fall had settled in the Swedish countryside. Committed to leading a healthy and spiritually rich life structured by the teaching and practice of the arts, they made Sweden their base until 1977 and lived there occasionally after that, until they separated in the mid-1980s.

The decision to move to Sweden in part reflected personal struggles Don was facing back home and in part Moki’s need to find creative outlets for her own work while raising a family and tending to domestic life. Elevating and aestheticizing ordinary experience was central to developing Organic Music. Don saw music “as a natural part of your day,” and Moki explained that, for them, “the stage is home and home is a stage.” 3 They built a sense of community by creating an open space for the collective production of art and music, whether at their home, in workshops for children and adults, or in concerts and other public events. Their aspirations were global in scope. Don’s early interest in world music was piqued by his engagement with Turkish musicians Maffy Falay and Okay Temiz, and, later, South African pianists Johnny Dyani and Abdullah Ibrahim (Dollar Brand), as well as by his travels to North Africa and India and his studies with Indian string players Ram Narayan and Zia Mohiuddin Dagar. Don and Moki coined the term “movement incorporated” as an alternative to the standard phrase “mixed media,” and they used the phrase to title a series of their immersive concerts. Here, incorporation refers not only to the integration of the auditory and the visual but also to the act of combining Western and non-Western music into a single practice that was collectively produced–one of the essential ideas behind what Don had called “collage music.” His repeated insistence that “it’s not my music” reflects a radical position: decentering the role of composer, he redefined the larger world of music and makers. This deemphasizing of authorship was tempered by his sensitivity to the exploitation and imbalance of power at the heart of appropriation: “It’s still incredible sometimes, what’s happening to black folks with the music itself. I mean the way the white pop world uses the roots of black music that they listen to and then put on dresses and makeup and bring in a negative thing that has nothing to do with the music.” 4

For Don, one reason to stop “playing for jazz audiences” was to remove himself from the commercial realm and open up his practice to sharing, exchange, and pedagogy. It is telling that Don and Moki’s first collaborative endeavor, Movement Incorporated, emerged at a workers’ association in Sweden. In this space, he and Moki could engage directly with their fellow musicians and with the audience, eliminating some of the boundaries and hierarchies that not only structured the world of jazz but had become increasingly prevalent in the commercialization and homogenization of music in the Western world.

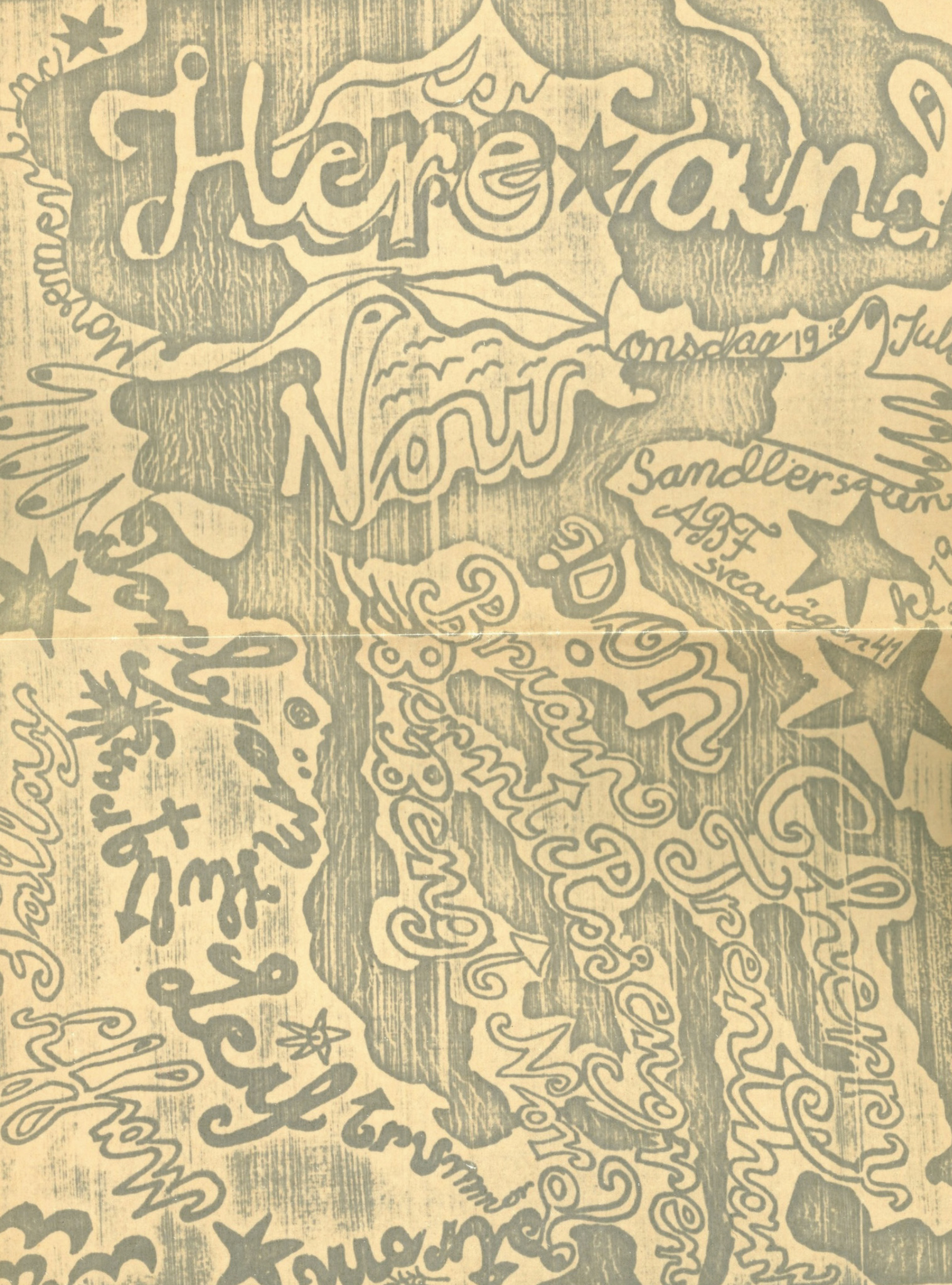

Flyer by Moki Cherry for July 19 Movement Incorporated concert at ABF Hall, Stockholm, Sweden, 1967.

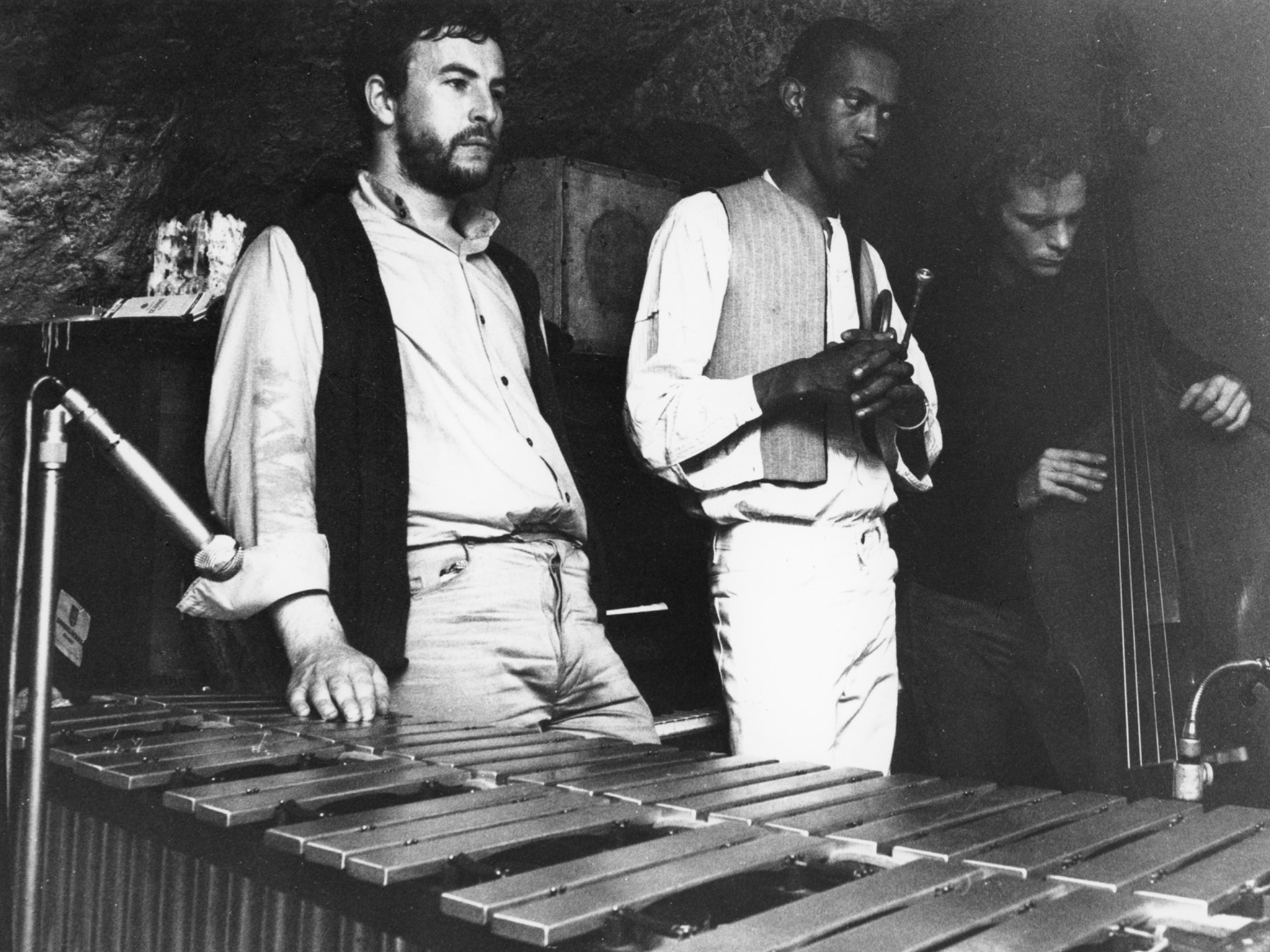

Movement Incorporated concert for French Television, 1967. Photo: Philippe Gras.

Movement Incorporated

On July 19, 1967, Don and Moki presented a concert under the banner of Movement Incorporated at the Sandler Salon, a classroom in Stockholm’s Arbetarnas Bildningsförbund Huset (ABF Hall), founded by Swedish trade unions and the Social Democratic Party. 5 During the concert, Don’s songs developed into long suites with themes flowing into one another and reemerging in an ever-changing musical montage. Within and around the themes were spaces for improvisation by some of the most skillful Swedish jazz musicians of the era: Bernt Rosengren on tenor saxophone and oboe, Torbjörn Hultcrantz on bass, Leif Wennerström on drums, with Bengt “Frippe” Nordström on a wounding soprano saxophone. 6 The band also comprised the American Brian Trentham on trombone and, on trumpet, Maffy Falay, who brought in Turkish melodies and rhythms. In a review of the performance for the British magazine Jazz Monthly, Keith Knox–a friend and chronicler of the Cherrys–wrote that Don was “wailing unbelievably on Indian flute.” The sound “ranged across the most complete gamut of Cherry’s music. . . . Much of the music was polyphonic in nature with a great deal of call and response, and there was an underlying exoticism which appeared strikingly in the peculiar, but very natural rhythms.” 7

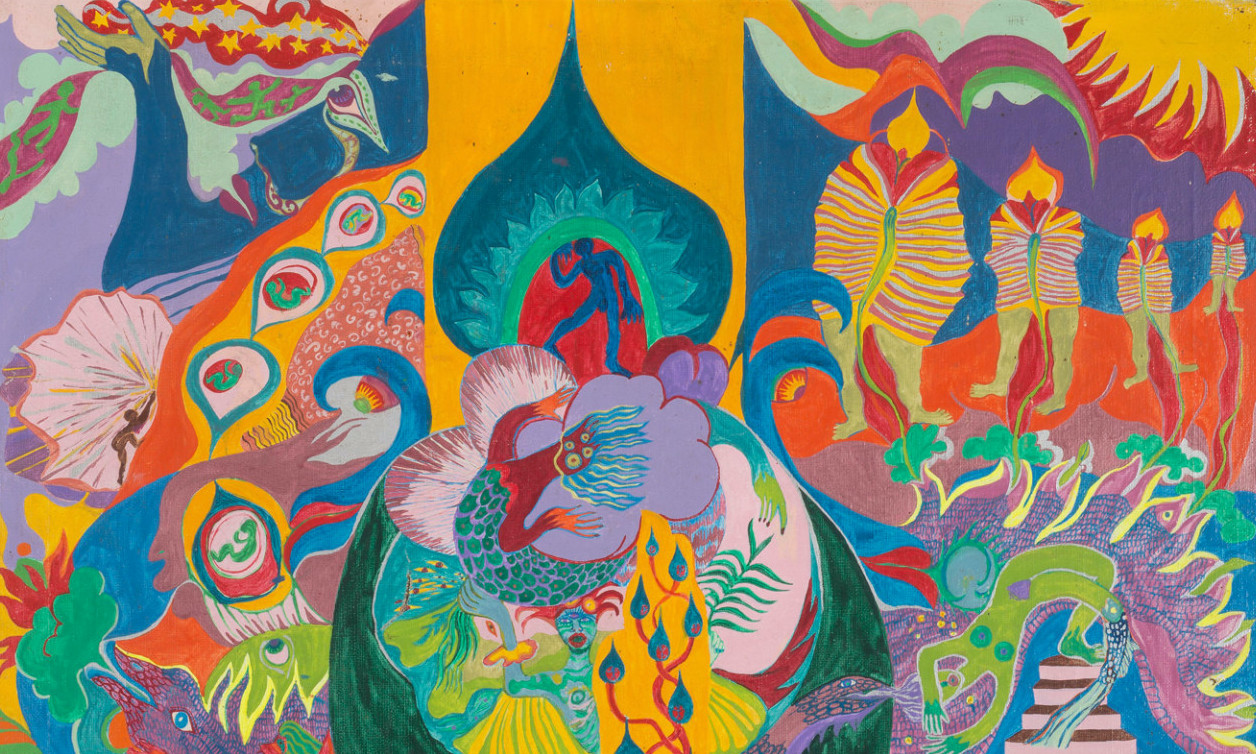

Don saw the 1967 Movement Incorporated concert as the first successful iteration of his and Moki’s effort to present music in a noncommercial environment. 8 Describing the event, Knox recalls that Don and Moki replaced the hall’s chairs with carpets to encourage the audience to sit on the floor with the musicians. “Around the walls above the audience were Moqui’s flamboyant paintings, startling in the subdued light. In the center of the room was the band, replete with candles and incense burners, disporting on a magic carpet.” 9 Don considered the use of slides (and later, film) in the Movement Incorporated concerts equally integral to their realization as the music. In addition to fusing the visual and the sonic, Movement Incorporated relied on Don’s combining international music traditions with jazz to create “collage music” when working with his first long-term group, Togetherness. The concepts that informed Movement Incorporated would eventually be developed into Organic Music Theatre, which drew in equal parts from Don’s musical experimentations and Moki’s work as a visual artist and clothing designer.

In a private note, Moki detailed her own contributions to the event: “We found the space and invited all of the musicians and some dancers. I made posters, designed the stage, and did live painting with the music. It sold out and was well-received on every level, so we were very encouraged. We were onto something that seemed to work and was great fun.” 10 After the first Movement Incorporated concert in Stockholm, Don, Moki, and Maffy Falay traveled together to Copenhagen for another show. Moki recalls: “We rented a beautiful old hall at Charlottenborg, the Academy of Art, and did the same thing—invited the musicians, made the posters, etc. I remember I used a park to paint huge chunks of fabric for the stage, and designed and made costumes. Some of the musicians were insects, Don was a tiger, some had simple face paint.” 11

Moki’s handmade poster for the Copenhagen concert, which took place on August 23, 1967, was an invitation to a symfoni for improvisers, with “sound by Don Cherry” and an “environment by Moki,” urging audience members to “bring your own carpet.” In the days leading up to the concert, Don met up with friends and other musicians while teaching themes and melodies to his group in preparation for the performance. The ensemble was composed of around twenty performers—professional musicians including Falay, Albert “Tootie” Heath, John Tchicai, and Hugh Steinmetz playing alongside amateurs Don had just met in town and invited to perform. In an interview given a few days before the gig, Don reiterates Moki’s message: “When people come on Wednesday, they should bring themselves and bring a carpet or a pillow—there are no chairs—or flutes, if they have any.” 12 The concert was called Welcome Live-in, and like the Movement Incorporated performance in Stockholm it included Moki’s art as well as a fireworks display and a screening of Herning 1965 (1966), an experimental film by Danish Situationist Jens Jørgen Thorsen.

A newspaper review describes the concert as an “orgy in rhythm” that was attended by a hundred of the city’s hippies and youth, with “oriental carpets, children, bells, reading materials, and bare feet.” 13 While the record Symphony for Improvisers had been released that same month on Blue Note, featuring an expanded ensemble of Cherry’s working group—Leandro “Gato” Barbieri, Karl Berger, Ed Blackwell, Henry Grimes, Jean-François Jenny-Clark, and Pharoah Sanders—the music Don presented in Copenhagen under the same title, with a mix of professional and amateur players, was perhaps a more literal embodiment of the name.

After Denmark, Don and Moki went to France. They wanted to do something similar in Paris, but had no clear plans. Running out of money to pay for their hotel, they were out on the street. As Moki recalls, Don took his cornet and one of her paintings to the Place de l’Odéon and started to play. A producer from French television took note and invited his ensemble to perform on air. 14 “We went there for a concert and we couldn’t find a place and didn’t have time to stay in Paris long enough to do that, but we did a color television show under the title of Movement. The decor was all done by Moki, and I used a trio at that time. The guitar player, Pedro Urbina, a classical guitar player who improvises, also. And the drummer, who is also in electronic music, Jacques Thollot.” 15

While Movement Incorporated existed only from July to September 1967, it laid the groundwork for the collaborative multi-media experiments Don and Moki would pursue over the next decade. As Moki remarks in her journals, her “spiritual experience” in Europe inspired her decision to abandon plans for her career in New York and put all her creative energy into this collaboration with Don. 16 That December, Don traveled briefly to the United States to seek opportunities for Movement Incorporated, but having no luck he returned to Sweden in February 1968. He was already committed to the interweaving of the arts as a governing concept: “There has to be a new presentation of music, a complete environment.” 17 With Movement Incorporated, he and Moki set the idea in motion.

Don Cherry’s International Quintet at Le Chat Qui Pêche, Paris, ca. 1966–67. Left to right: Karl Berger, Don Cherry, Jean-François Jenny-Clark. Photo: Erich Klemm.

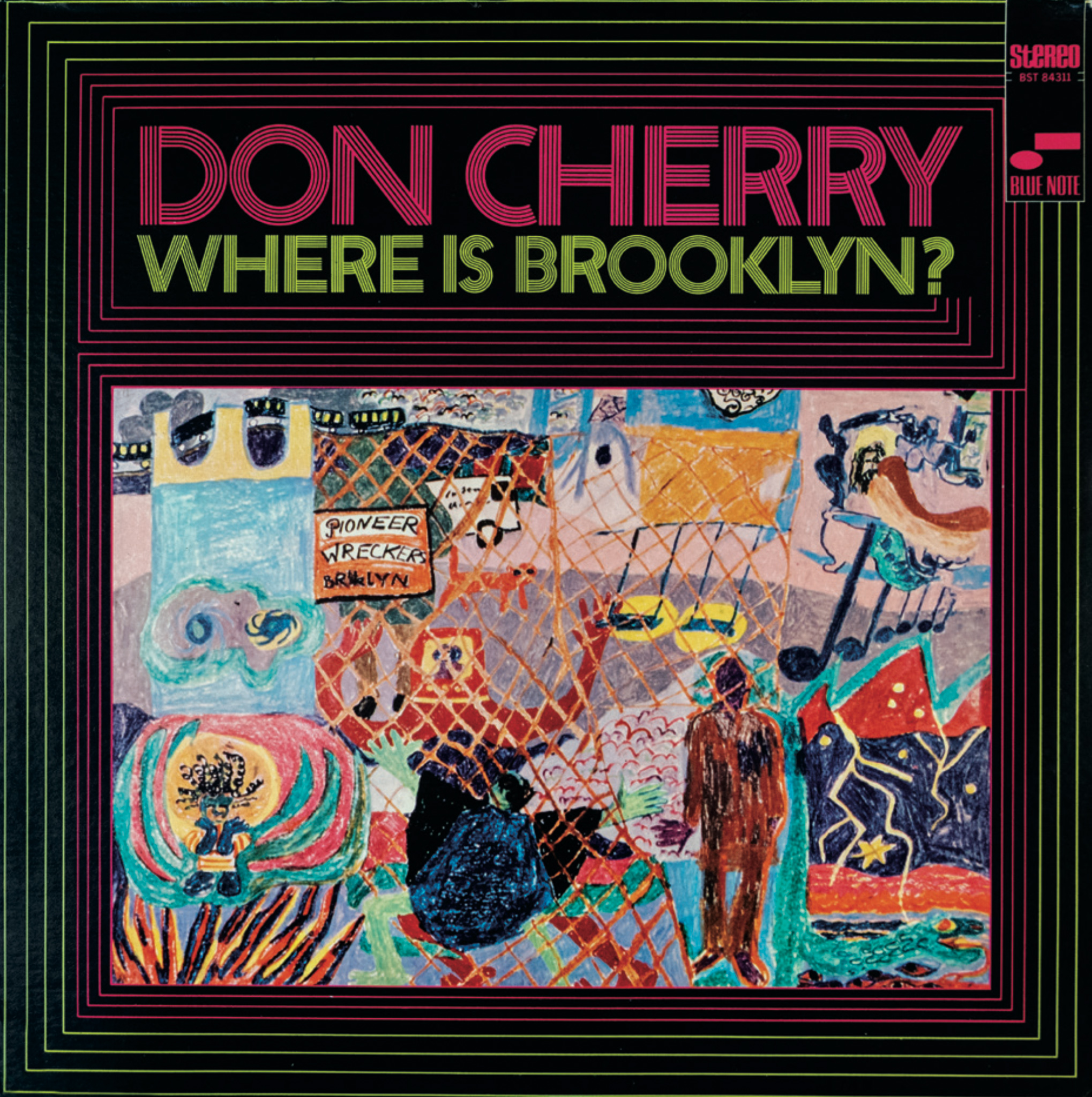

Album cover for Don Cherry’s Where is Brooklyn? (Blue Note, 1969), illustration by Moki Cherry.

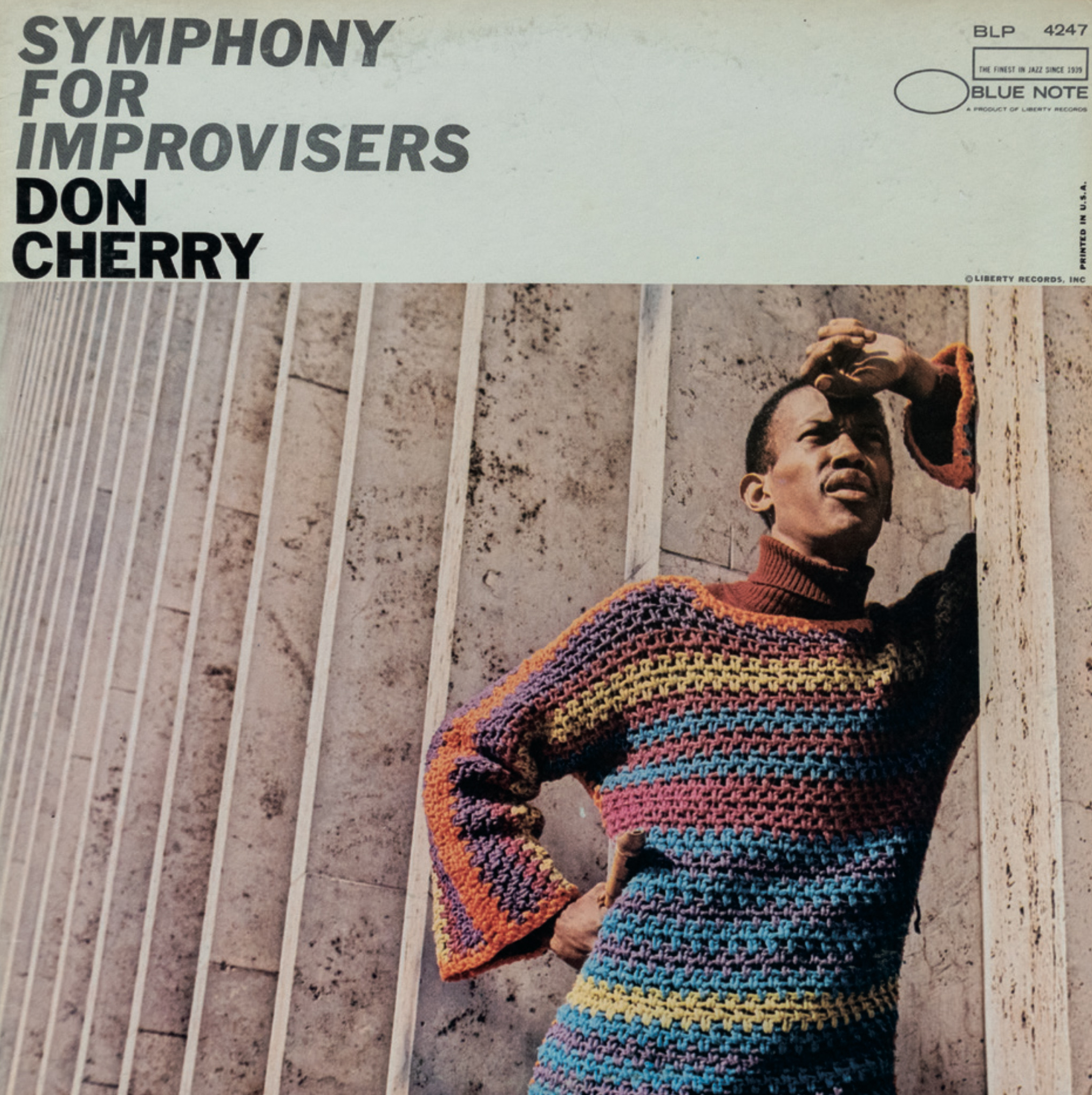

Album cover for Don Cherry’s Symphony for Improvisers (Blue Note, 1967).

Don, Moki, and the International Quintet

Don and Moki met on January 17, 1963, when Don was performing in Stockholm while on tour with the Sonny Rollins Quartet. 18 Moki had seen the Rollins Quartet at the Konserthuset and, after the show, headed to the smaller Golden Circle, where Johnny Griffin’s group was playing. Don and the rest of Rollins’s band were already there, and some of them were sitting in with Griffin. According to Moki, Don approached her group of friends and asked to speak with her; the two immediately hit it off and spent the evening talking. When they parted that night, Don told Moki he would come back to see her. 19 Moki was nineteen and just starting her studies at Beckmans Designhögskola, an alternative art and design college in Stockholm. A young painter with a strong interest in free jazz, she regularly attended concerts at the Konserthuset and the Golden Circle, which was more experimental and hosted artists such as Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, and, later, Cherry’s group. She was familiar with Don’s music through his recordings with Coleman and was excited for Don to meet the saxophonist and composer Albert Ayler, whom she had befriended on his trips to Sweden in 1962 (and who later took her up on her offer to let him use her painting studio as a place to rehearse). 20

For the next couple of years, Don and Moki’s reunions occurred sporadically, on the occasions when Don was on tour and perfor ing at the Golden Circle, first with New York Contemporary Five in November 1963 and then with Albert Ayler in October 1964. 21 Though Moki and Don had spent relatively little time together, they soon became close. After the tour with Ayler, Don traveled to Denmark and from there made his first trip to a non-Western region, to Joujouka, Morocco, with the Danish artist Åge Delbanco (also known as Babaji). During his brief stay he met and performed with the Master Musicians of Joujouka. 22 On his return trip to Europe in December, he went to Stockholm to see Moki and they decided, in her words, “to find a way to share our lives together.” 23

In the summer of 1965, Don and Moki took their first trip together, to Munich, where Don recorded the soundtrack for George Moorse’s film Zero in the Universe (1965). 24 After Munich, the couple continued to Paris, where Don had an engagement at the jazz club Le Chat Qui Pêche with his newly formed quintet and Moki explored the fresh food market Les Halles and the plentiful fabric shops of the city.

Paris served as the center of Don’s activity for much of 1965. While there in April, he assembled the group Togetherness, also known as the Don Cherry Quintet, the Complete Communion Band, and the International Quintet, comprising Karl Berger on vibraphone and piano, Gato Barbieri on tenor saxophone, Jean-François Jenny-Clark on bass, and Aldo Romano on drums. Cherry and the ensemble had a lengthy engagement at Le Chat Qui Pêche in April, June, and July, and returned several times in 1966 and 1967. During these years, they also toured extensively in Europe and recorded a number of releases for Blue Note.

The Quintet represented something new in the world of jazz in at least two notable respects. First, it was international in its constitution, with each member hailing from a different country: Don from the United States, Barbieri from Argentina, Berger from Germany, Jenny-Clark from France, and Romano from Italy. This was important to Don, who commented on the value of the musicians teaching and sharing songs from their respective nations–how it brought them closer together not only musically but also personally. 25 Don already had a strong interest in international music and song, and the band’s diversity, the nature of its dynamic, and the relationship of the individual musicians to the larger ensemble would all powerfully inform his creative and educational practice. He imagined a band whose members could be “alone together,” merging solo performances into a unified whole.

The second distinctive attribute of the Quintet had to do with “collage music.” Unlike the suites of Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus–where the different parts would be planned and arranged–Don’s “collage” compositions were built entirely on improvisation. Not just the solos, but the entire piece. The parts, order, duration, and tempo were never decided in advance. Everything emerged as the musicians played—no signs, as Romano says, “no nothing.” The live recordings from Jazzhus Montmartre in Copenhagen in 1966 demonstrate how the material changed and was reworked over the span of the band’s engagement. The song “Complete Communion,” for instance, was played each night, always with new variations on its length and structure. 26

No matter how involved he was, Don never thought of the group’s compositions as his own. Berger recalls that at this time, Don was constantly listening to a shortwave radio, with which he could tune into music from all around the world; this access, combined with what Ornette Coleman used to say was Don’s “elephant memory,” provided the basis for the group’s compositions. As Berger says, Don “could hear a melody once and just know it and be able to reproduce it. Then he would come to the rehearsal, and whatever he had just heard he would pound out on the piano three, four times. He also expected us to have an elephant memory. . . . We were just trying to catch whatever we could.” 27 According to Romano, Don would “play a few notes and then we would know what to do.” 28 Don later observed that his compositional process mirrored urban life, where “you go around a corner and there’s another life beginning, another whole environment.” 29 In a sense, this is the idea of collage: bringing together pieces, each containing its own history and stories, to make something larger, rather like blocks composing a city.

In the fall of 1965, Don’s Quintet played for two weeks at the Golden Circle. Moki, who was still in design school, created a unified aesthetic for the performance by dressing the band all in white. One of the evenings was recorded on video by Hans Isgren and, subsequently, Swedish artists Ture Sjölander and Bror Wikström turned it into one of the first-ever works of video art, Time, 1965–66, which was shown on Swedish television. Moki credits this performance as marking the start of her active involvement with Don’s music, a collaboration that would increase in rigor and complexity as their working relationship grew over the years.

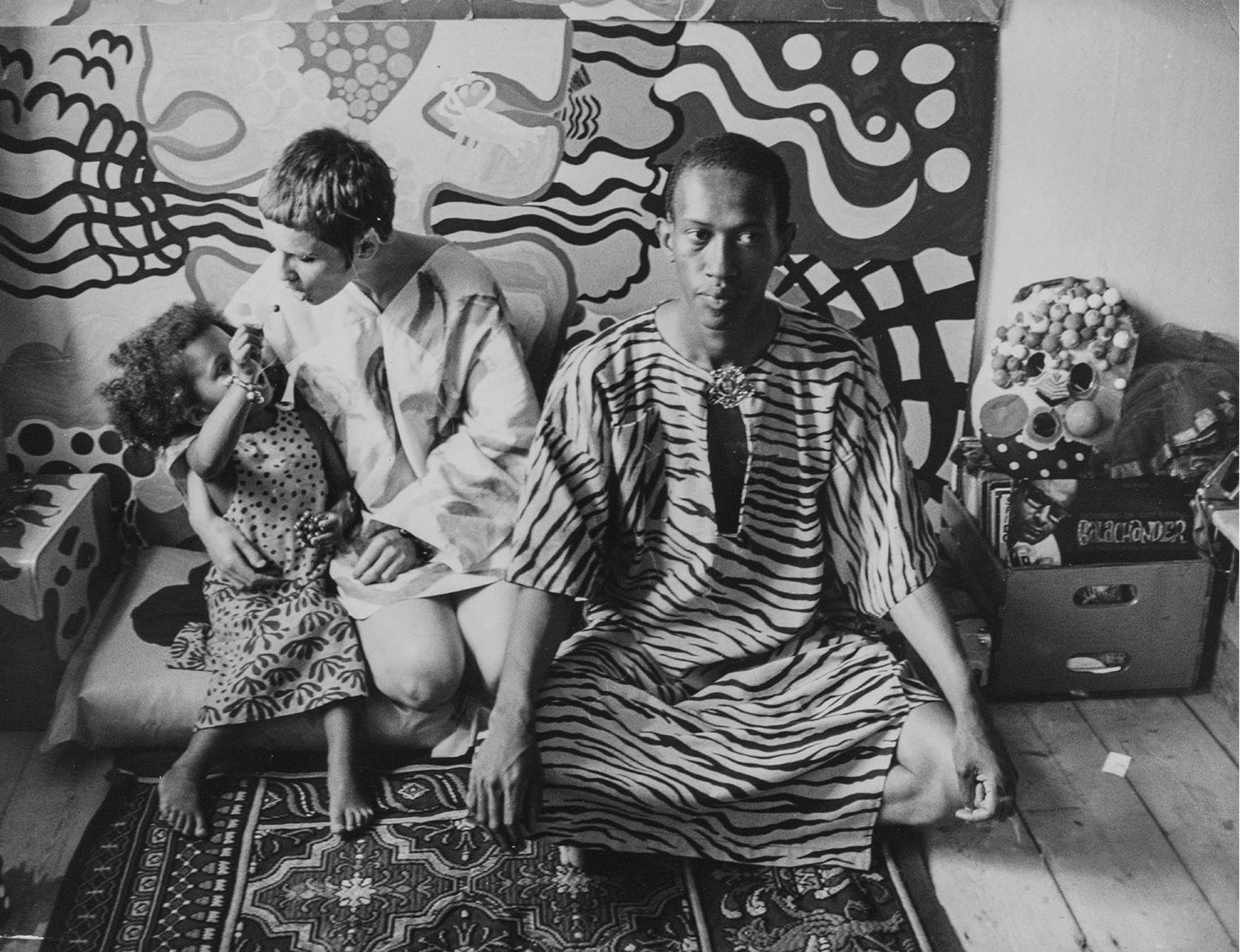

Toward the end of 1965 and throughout 1966, Don traveled back and forth between Europe and New York. During this time, he recorded three albums for Blue Note: Complete Communion (1966) in December 1965, Symphony for Improvisers (1967) in September 1966, and Where Is Brooklyn? (1969) in November 1966. Moki’s work animates the cover of Symphony for Improvisers, which features a photograph of Don wearing a colorful striped sweater she designed for him, and the cover of Where Is Brooklyn? (see p. 50), on which one of her intricate drawings depicts an abstract cityscape. In 1966, Moki and her two-year-old daughter Neneh went with Don to New York, where Moki pursued a career in fashion and design, selling her clothing to shops including Design Research and Henri Bendel. She continued to design clothes and costumes for Don’s ensembles, and her diaries from this time are full of sketches and ideas. She eventually met the American fashion photographer and filmmaker Bert Stern, known for his film Jazz on a Summer’s Day (1959), which documents the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival. Reminiscing in the early 2000s, Moki remembers how Stern “wanted to sponsor me as an artist-designer. The fact that I got the recognition and a huge opportunity was good for my identity. I guess it gave me the courage to choose to live and work with Don and to simultaneously be with my child, soon children.” 30

Toward the end of 1966, the couple rented the midtown New York venue Town Hall to put on a concert called “Elephantasy,” a title they would use on several occasions in the coming years. The performance required four different sets of musicians over the course of the evening, among them Gato Barbieri, Karl Berger, Pharoah Sanders, Henry Grimes, Ed Blackwell, Rashied Ali, and a few others. The show mostly consisted of Don’s compositions, but included a single work by Ornette Coleman, called “Lighthouse.”

Though Moki had made a promotional poster and taken out an advertisement in the Village Voice, very few people showed up. While the concert succeeded in other respects, the lack of attendance signaled the difficulties that Don and Moki would face in New York. Among other issues, Don was fighting a heroin addiction he would battle for the rest of his life. In her diaries, Moki alludes to the situation without addressing it directly. In a reflection from 2008, she remarks, “Arriving in NY, I had no idea the struggles the musicians were still enduring in the US.” 31 Beginning to spend more and more time away from urban centers in the States and abroad, by launching Movement Incorporated, the Cherrys hoped to create a sheltering and inclusive space: “The idea was to create an environment/atmosphere, the stage being the home and the audience part of it.” 32

From December 1968 to February 1969, Don and Moki rented a loft at 55 Chrystie Street in New York. Soon finding it impossible to live on the Bowery with two children, they set off for upstate New York, settling in Congers in March. Don, Moki, Neneh, and Eagle-Eye were joined by Don’s two other children, Janet (born in 1956) and David Ornette (born in 1958), for the summer. Moki decorated and painted the house, as she had her previous apartment in Stockholm, but by the end of the summer the family was forced to vacate the property, the prejudice against interracial couples making it impossible for them to buy it. 33 Don and Moki took Neneh and Eagle-Eye with them to Amsterdam, purchasing a van and driving north for concerts in Norway and Sweden, collecting Okay Temiz along the way. Eventually, they made their way to Turkey, stopping off in Istanbul and heading on to Ankara. In Istanbul, the family would meet James Baldwin, who engaged Don to make music for a production of John Herbert’s play Fortune and Men’s Eyes (1967). 34

Before these travels, Don had been offered a teaching residency at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire through the musician Jon Appleton for the winter of 1970. The family returned to the States that January and settled in Norwich, Vermont, just across the river from the college. Don taught one course that was reserved for instrumentalists and one that was open to all students. He described the focus of the class for musicians as “Orchestra of free form. Exploring mysticism of sound. Vibrations. Harmony. Form. Rhythm. Abstract Sound” and the one open to the general student body as “Possibilities. Impression. Expression. Feelings and Forms.” 35 The classes were so popular that he was asked to repeat them in the spring. In addition to teaching, Don had a residency at the college’s Hopkins Center for the Arts and presented a number of concerts in and around the area.

Following the models he used for workshops in Sweden and for instructing young children, Don’s classes consisted of listening to and playing melodies and compositions from around the world. He invited Abdullah Ibrahim, Johnny Dyani, and Okay Temiz to visit as guest lecturers. 36 Don also shared and taught pieces from Ornette Coleman, Alice Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, and Leon Thomas, along with his own music.

Don referred to one class’s final performance as “living opera,” borrowing the language and spirit of the New York avant-garde troupe the Living Theatre. To realize this concept, Moki collaborated with students to create carpets, costumes, and backdrops, as she did for the classes, concerts, and lectures Don gave on campus. The couple’s 1967 collaborations seemed to be very much on Don’s mind. As he describes it, one of the concerts he and Moki held at Dartmouth, titled “Elephantasy,” featured scenography by Moki that recalled the earlier Movement Incorporated concerts 37 (as did another performance, Peace Piece, held at the New England Life Hall in Boston). 38

Having witnessed, on the first day of class, the self-segregation of white and black students, Don sought to break down the racial divide through music: “We did certain things . . . where everyone had a sensitivity of touch, becoming close to each other.” 39 He and Moki also opened their home to students on weekends so they could all get to know one another. It was essential to Don’s vision that each musician contribute uniquely to the shared creation, and he used his spontaneous conducting approach to advance that ideal. Speaking with Keith Knox, he said, “It worked out fine because it leaves the freedom for the musicians to use their own individual self-expression collectively. And it still creates a completeness in form.” Later, he added:

And it’s not really “ours” because we’re getting into that “mine” and then there’s also this “mine” of “mine.” But we’re actually trying to realize this universal awareness of himself. I feel like the revolution is inside–revolution, revolution–because that’s the journey, the most dangerous journey. The hardest journey is the journey inside. It’s strange me saying that, being a traveler like I am, but the revolution is really inside. 40

The experience at Dartmouth left a lasting impression on Don and Moki that would solidify the next stage of their collaboration. When the residency came to an end in the summer of 1970, they returned with their family to Sweden. Buying another van, they looked for a permanent home there. After looking into purchasing property in the north, Moki learned of the abundance of decommissioned schoolhouses in the south and contacted a real estate agent in Hässleholm about a property in the locality of Tågarp, forty miles from where they were at the time; when they arrived, there was a rainbow over the schoolhouse. They bought the building, and it became the base for their activities. It provided ample space for visiting friends and artists, rooms for their own respective studios, a stage for presenting concerts, and a place where they could host educational classes and workshops for children.

Gathering at Tågarp Schoolhouse. Left to right, descending: Steve Roney (standing on top step), Anita Roney, Don Cherry, Jane Robertson, Moki Cherry, Kerstin McNeil, Eagle-Eye Cherry (standing near bicycle on right), ca. 1973.

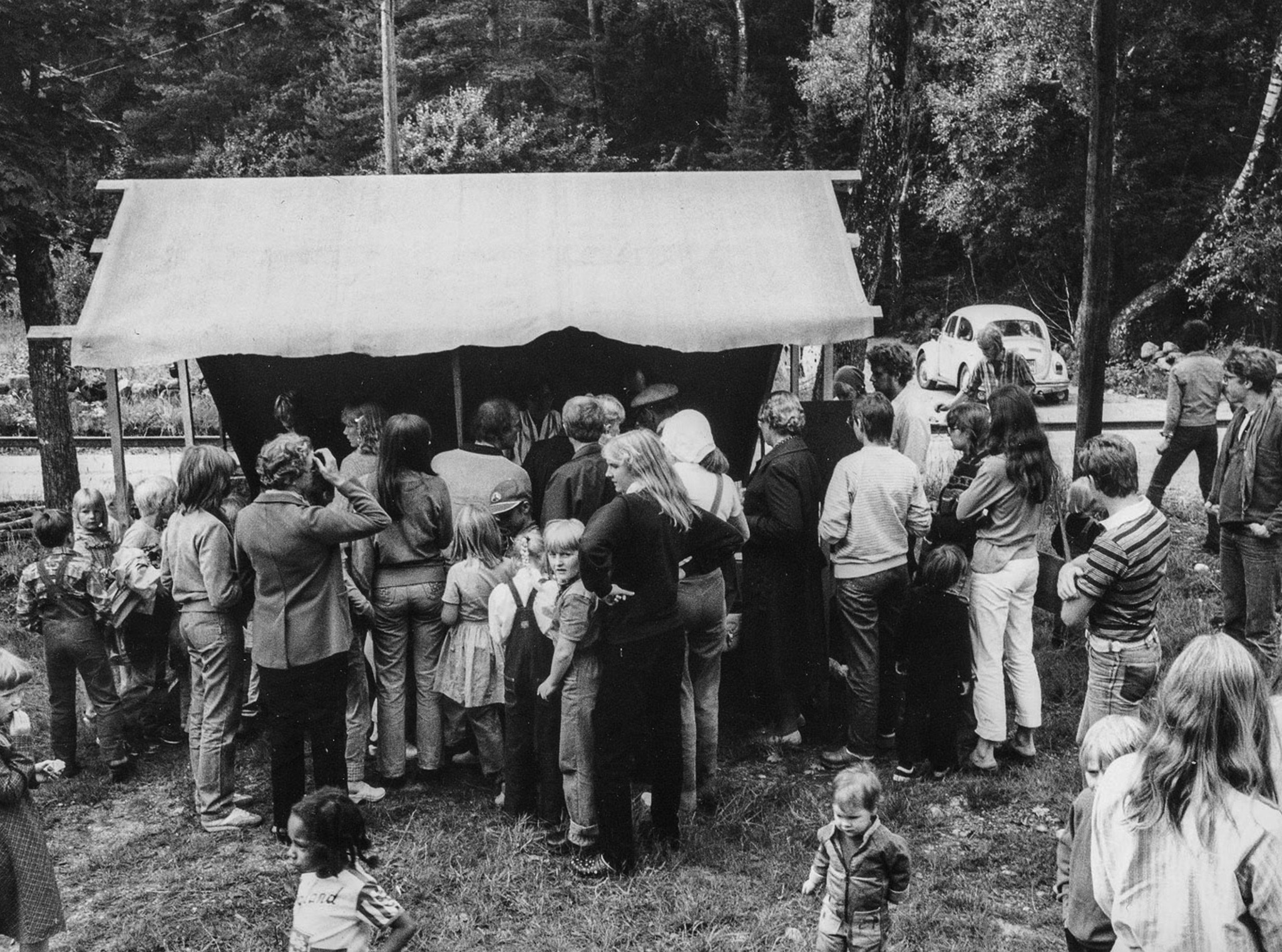

Event at Tågarp schoolhouse, ca. 1977.

Don and Moki Cherry with Neneh Cherry in Gamla Stan, Stockholm, 1967. Photo: Peter Bjorkegren.

Organic Music

A confluence of influences shaped the development of Organic Music Theatre, among them rejection of the conditions black artists were offered in the States; exposure to other music cultures—Turkish, Indian, and North African; and the benefits of the welfare system the Social Democrats had established in Sweden. As Knox writes about Movement Incorporated: “There was concern for the environment and the real status of improvised music. They decided to get together to teach each other and learn how to dissolve the artificial boundaries imposed on music by commercial requirements.” 41 While Movement Incorporated represented the development of Don’s concept of collage music, Organic Music Theatre embodied an increasingly holistic approach to the production and distribution of music, treating it as integrated with the living environment in which it was presented. His thinking about the organization of individual parts within the whole reflected the ideological outlook he brought to his pedagogy. The creation of Organic Music Theatre was as much a marker of the evolution of his artistic concept as it was tied to the couple’s new home in Tågarp.

Ornette Coleman, with whom Don played throughout his career, offered a model for creating an alternative space for music. In April 1968, Coleman had acquired a loft at 131 Prince Street in lower Manhattan, later known as Artist House, that would serve as his home, rehearsal space, concert hall, and gallery. In the early 1970s in New York, especially SoHo, musicians were opening their own multifunctional residential and performance spaces. Jitu Weusi and Aminisha Black’s The East–a performance site and Black Nationalist educational complex that hosted the children’s program Uhuru Sasa Shule (Freedom Now School)–was founded in Brooklyn in 1969, right before Don started teaching at Dartmouth. The music wing of the organization hosted concerts by Pharoah Sanders and Leon Thomas as well as other musicians close to Don, such as Dewey Redman and Abdullah Ibrahim. While Don did not have a direct connection to the institution or to Black Nationalism, he was undoubtedly aware of efforts underway in the States to promote the concept of self-reliance, especially in relation to education.

Don and Moki were urgently concerned with protecting Don from his addiction, and the Swedish countryside seemed to be the ideal place for recovery. In a 1971 interview with the jazz drummer Art Taylor, Don explains, “I had lived in cities most of my life, and I reached a point where I had a polluted brain, a polluted soul. The only cure for me was nature. I settled in a forest, on the earth, without boundaries.” 42 Don’s desire to live a healthier lifestyle and to play his music in places other than urban nightclubs and bars would become central to his thinking and his music. The idea of health—and health food—runs through compositions from this period such as “Hummus,” “Brown Rice,” and “Elixir.” In Tågarp, Don and Moki began growing their own produce, and Moki would prepare meals in a communal setting that welcomed friends and family. Everyday activities began to take on the theatricality of the space, where Moki’s artwork functioned as frame and backdrop. Moki’s saying “The stage is home and home is a stage” takes on a double meaning when considered in relation to her dedication to helping Don overcome addiction. An alternative environment for music was combined with the discipline and rigor required to promote wellness within it. The centering activities taking place at the schoolhouse–communal living, educational classes, and workshops–slowly began to replace the stress and discontinuity of touring.

During the summer of 1971, less than a year after acquiring the schoolhouse, Don and Moki were invited to participate in “Utopier och visioner 1871–1981” (“Utopias and Visions 1871–1981”), an exhibition held at Moderna Museet in Stockholm. Organized by Pontus Hultén, the museum’s director, and Tonie Roos, a close friend of Moki, the project was accommodated in a geodesic dome where the Cherry family lived and worked for seventy-two days. As there were no “concerts” or public performances in the traditional sense, the event simply transposed the activities taking place in Tågarp to a public institution.

Hultén proposed “Utopias and Visions” as an exemplar of “living art.” 43 The museum took out ads in the local papers inviting the public to “be part of creating a musical-aesthetic situation with Moqui and Don Cherry.” 44 The dome stood just outside the museum building, and the family spent their evenings in the old Navy prison next to it, where they had access to a kitchen and rooms to sleep in. During the day, Don and Moki worked and performed inside the dome, engaging visitors in live music workshops. The daily performances featured members of the Swedish jazz scene, including saxophonists Rosengren and Tommy Koverhult, bass player Ove Gustavsson, and trumpeter Falay, as well as forward-thinking musicians like Bengt Berger, Fluxus artists Bengt af Klintberg and Takehisa Kosugi, and the Taj-Mahal Travellers, who were touring Sweden that summer. Setting up his drums, Okay Temiz stayed for almost the entire length of the project. In addition to hanging her tapestries and installing her soft sculptures in the performance space, Moki painted a large mandala on the floor over the course of the residency.

Don started working with children as early as 1968, giving concerts at public schools in the Bronx and Sweden. 45 In addition to conducting ABF workshops that year he visited several summer camps for young musicians, giving concerts and workshops alongside Falay, Torbjörn Hultcrantz, and Leif Wennerström, playing the same material they would have performed in concert. In the fall of 1971, a six-episode children’s music program by Don and Moki called Piff, Paff, Puff was filmed for Swedish national television. Set at the schoolhouse decorated with Moki’s scenography, the show featured Don, Moki, Neneh, and Eagle-Eye along with children from a nearby school. It aired the following spring in collaboration with the Swedish producer Björn Lundholm. Each of the ten-minute episodes, essentially non-narrative, opens with Don blowing a conch shell to greet the children as they arrive in a van before gathering in the schoolhouse. The kids play and learn with Don and Moki, making collages, sewing clothing, baking, and playing music. Don accompanies the children on a variety of instruments, including the piano, cornet, tablas, flute, and kalimba; in one episode, Moki is seen painting drums while a three-year-old Eagle-Eye plays them. The musical material is by Abdullah Ibrahim or Don himself (compositions such as “Desireless” and “March of the Hobbits,” two pieces he would workshop with professionals a few years later for his 1970 Jazz Composer’s Orchestra commission, Relativity Suite).

Elefantasi was a radio program whose segments, running a little under ten minutes each, were broadcast by Swedish national radio in 1972. It is somewhat more narrative in approach and features music by Don and a voiceover by Moki inviting children to join them and their friend Fantasimon, a flying elephant, in an imaginative journey over the sea. Fantasy and creativity were key concepts for Don and Moki, in both their practices and their pedagogy. For Don, the children “are still free to use their imagination, to listen and take part, which I think is important in music. To be able to listen and take part.” 46 The Cherrys believed that young people could access the essential elements of music very quickly and directly; in many ways they were more adaptable than adults to Don’s modes of composing, playing, and teaching.

The couple traveled together in 1971, touring in France with Han Bennink in August and then Don continued his independent work that year recording Science Fiction (CBS, 1972) with Coleman in September, and leading the New Eternal Rhythm Orchestra in Donaueschingen, Germany, in October. 47 He resumed his collaboration with Moki in the summer of 1972 with the first Organic Music Theatre concert at the Festival de jazz de Chateauvallon and a workshop and concert in late November 1972 at New York University called “Relativity Suite,” followed by a concert at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1973. 48

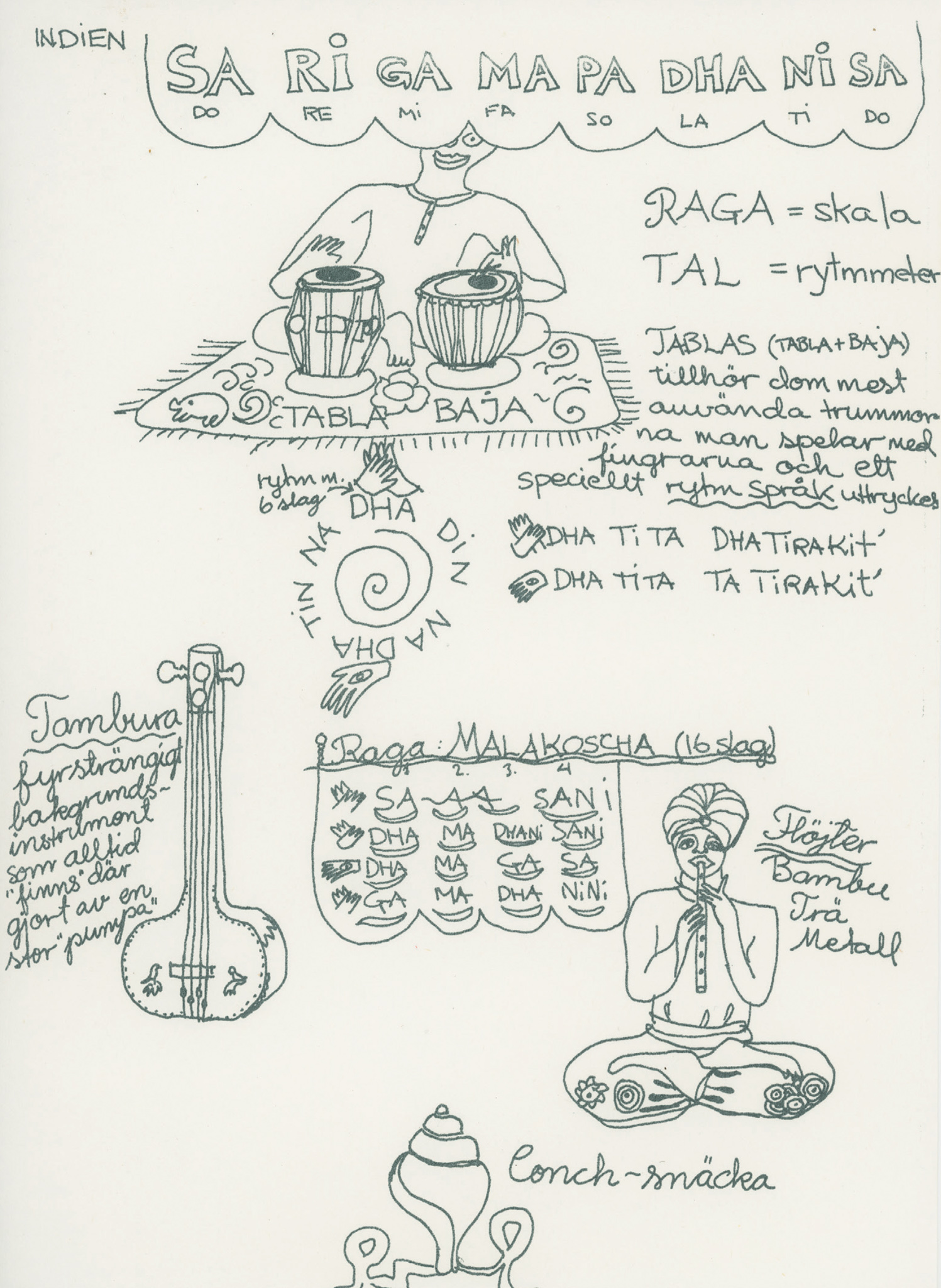

During 1973, Don and Moki were joined in their educational work by Christer Bothén (whom Don had met in Gothenburg in 1972), Bengt Berger, and Annie Hedvard. Over the course of at least three tours of Swedish schools financed by the Swedish governmental organization Rikskonserter, the group, in different formations, conducted nearly ninety workshops in locations as disparate as the far north and remote south of the country. During the sessions, children sang along to simple lyrics legible on vividly colored fabrics sewn by Moki. The schools would prepare for the group’s arrival using creative teaching material sent along beforehand. These included stencils of Moki’s annotated drawings of instruments from Africa, India, Tibet, and elsewhere. The atmosphere of these workshops was casual and open. They were all about playing, conversing, and listening to music. A central part of Don’s own playing, he said, was maintaining a feeling from his childhood:

The music that I play, that I’ve always been known to play, I have always tried to remember the first thing, the time when my mother first gave me a horn, the feeling of having it and this thing of going to play music, so that feeling to me, through as much music as I’ve learned, I still remember just that feeling when I first got that horn. And that’s what’s important to me. That’s what music is really about–the infant happiness, the infant happiness, beautiful! 49

The way Don taught children was not that different from his process with adults. In the mid-sixties, he had worked with many European jazz musicians who would later become famous, such as Joachim Kühn from Germany, François Tusques from France, and Bo Stief from Denmark, among others. He taught by showing, without written scores, and with minimal lecturing. In the 1968 ABF workshops he focused on overtones, “ghost sounds,” Turkish time signatures, tones–in breathing, singing, and droning–collective improvisation, silences, “surprises,” and Indian scales. 50 Many of his students were musicians in his band. 51 The workshops took place in February and March, and at the beginning of April he recorded parts of a newly written suite, Feelings and Forms, for Swedish national radio. Listening to the recording, one can hear the principles of the workshops in the odd meters, held tones, and group improvisations; an abbreviated version of a Turkish folk melody shows its distinctive rhythms.

One of the tracks on the record Organic Music Society (Caprice, 1973) is the result of a workshop led by Cherry and Temiz at the Bollnäs Folkhögskola (Bollnäs People’s High School). They led a group of musicians who were studying European classical music for the summer in a performance of work by Terry Riley and Abdullah Ibrahim. This is one of the few recordings of such sessions aside from a collection of tapes made during the ABF workshops in Göran Freese’s collection at the Centre for Swedish Folk Music and Jazz Research in Stockholm. 52

The period of 1973–76, when Organic Music Theatre cohered as Don and Moki’s way of bringing together music, art, and life, was also a time when Don slipped under the media radar. Playing music for its own sake rather than only in paid concerts was of paramount importance to Organic Music Theatre. Swedish drummer Bengt Berger, who worked frequently with Don during the 1970s, says of his visits to Tågarp: “There was no difference between gigs and practicing. It was about creating music all the time. And it was about learning all the time. [Don] was very fond of learning new songs and making music of it right away.” 53

The Cherrys were constantly either on tour or getting ready to go on tour. According to Moki, “Before these tours all the musicians used to come to Tågarp for rehearsals and preparations. I used to work on sets, clothes, cooking, mulch the garden for there to be one by the time we were returned home, make dukiburgers 54 for the road, packing the bus with all the various gas stoves etc.” 55 One of the major performances was in Alassio, Italy, in September 1973. The group had now expanded to become a septet. 56 Italy became the most popular host of Organic Music Theatre, with concerts attracting thousands of fans during three national tours from 1974 to 1976. 57 In October 1973, the group performed in Poland with Bobo Stenson joining on piano and Moki on tanpura. The first half of 1974 was spent traveling: between January and March, Don was in India studying with Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar, the great master of the rudra vina, and in May, the whole family went to Japan. While Don would continue to use elements of Organic Music Theatre (as well as the naming convention “Organic Music”) for a wide variety of projects throughout the seventies—including smaller collaborations and duets featuring Moki’s tapestries with Ed Blackwell, Han Bennink, and Naná Vasconcelos—the underlying preparatory process was not as present. By the autumn of 1977, Don and Moki had purchased a loft space in Long Island City, New York. About that time, the story of Organic Music Theatre had nearly faded away, and with his new groups, the trio Codona and the quartet Old and New Dreams, Don altered his musical path again.

Don Cherry with the Taj-Mahal Travellers during “Utopias and Visions” at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 1972.

Production photos for Piff, Paff, Puff (1971).

Children’s workshop handout depicting instruments from around the world with illustrations by Christer Bothén and Moki Cherry, ca. 1973.

Bobo Stenson (seated on far left), Jan Robertson (cello), Christer Bothén (sax), Eagle-Eye Cherry (seated in foreground), Don Cherry (horn), Palle Danielsson (bass), Moki Cherry (tanpura).

Christer Bothén (sax), Moki Cherry, Eagle-Eye Cherry, Don Cherry.

“It starts in the home”

The international jazz critics selected Don Cherry as this year’s [1963] trumpet talent deserving of greater recognition. This award of DownBeat magazine will hardly help him find more work, now that he is no longer with the Sonny Rollins group. Winning such an award might help Cherry work if he also wanted to play like Miles Davis et al, or maybe, said he did, or at least could spin a bass on his head while holding a note (as Roland Kirk did recently at the Village Gate). But, unfortunately, all Cherry’s got going for him is his musical intelligence, which mostly will lead to starvation on the New York jazz scene. Club owners do not care especially for intelligent black musicians. 58

—Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones)

Though jazz critics realized the depth of Don’s talent early on, his life was one of struggle. Amiri Baraka’s wry summation appeared in the French journal Africa Latin America Asia Revolution in 1964, a few years before the Cherrys felt compelled to relocate to Europe. 59 In New York and Los Angeles, Don endured hard times, financially and psychically, as he wrestled with addiction, leading to arrest and jail time. Throughout his life he contended with racial inequality on a deep and personal level. In an interview with Knox from 1970, Don breaks his usual silence on political issues to address black activism and his understanding of the dialectical relationship of politics and spirituality:

In America now there are many, many programs. One of the joyful things that happened is in Newark, where many people had worked to have a black Mayor [Kenneth Allen Gibson], and it worked out. And that’s a way, you know, I mean that’s one way. Then there are many people working, both black and white, to expose the injustice that is happening to the Black Panthers. Even myself, I have done things, worked on it. But that’s this thing of problems, problems come from the mind. It’s like politics, politics has to be problems because politics is all from the mind. You don’t feel in politics, you just have to think about, the action is from the mind. But to contradict politics is spiritualism you know and that’s the balance, they’re both essential. I say that in regard to the black movement in America, I think it is very essential. I’m really involved in music and I feel that music should be free of politics, because it’s a direction which I say is contradictory, so it should automatically be free of politics and also free of culture. Culture is culture-for-sale. 60

While Don here insists that music is free of politics and aligned with spirituality, he stresses the need for the two domains to exist in mutual opposition. Remembering his time at Dartmouth, he touches on the war in Southeast Asia while explaining that he did not himself participate in the student strike. Condemning police violence against people of color and US laws prohibiting interracial marriage, he proposes that the most effective resistance to structural racism lies in establishing an alternate social environment—paralleling Moki’s dictum, “The stage is home and home is a stage.” His outlook brings Buddhist pacifism to the militancy of the Nation of Islam. 61 “[Elijah Muhammad] believes that Islam is the nature of the black people and Islam is a beautiful way of life for use in the home. It starts in the home, if there’s anything that’s going to happen in society, it must start in the home. Once it starts in the home it then vibrates and radiates out.” 62 Don and Moki’s home, and the ethos that emanated from it, were founded in their deeply held belief that art and education can bring people together in a communal social arrangement that will be beneficial to all.

Don Cherry at Daisy Cherry’s house in Watts, Los Angeles, California, ca. 1976. Left to right: Don Cherry, Daisy Cherry, Eagle-Eye Cherry, Neneh Cherry, Lisa Lawrence. Photo: Moki Cherry.