Curtis Cuffie sculptures, ca. 1994–96. Photo: Katy Abel

I make sculptures for spaces that need life. I put my art in public places for people to catch love, secrets, and respect. See, art to me is a dream, without being asleep. It comes to me in a puzzle. When I go to sleep it vanishes from me. When I awaken I go seek it in the most unlikely places. The first piece of art I ever made was of turning a mop upside-down. The first thing I noticed was my Grandma’s head, face, and hair. So I started putting clothes on it and making a body under the head—the arms, the legs, and the feet. So behind that, it’s shown me everything to proceed forward with my art. Little works of art, monuments, invisible art. My art goes in many dimensions. See, being an artist is a very risky profession. You’ve got to be very deeply concerned with your creation. Not just what you make of your art, but how it affects others. My art is medicine. I want my art to show people that we’re all equal. To make the world more fair. I want my art to be like a prophet. Giving the world what it needs. My art gives people company, comforting everybody. It’s a very good friend. That’s what I hope for.

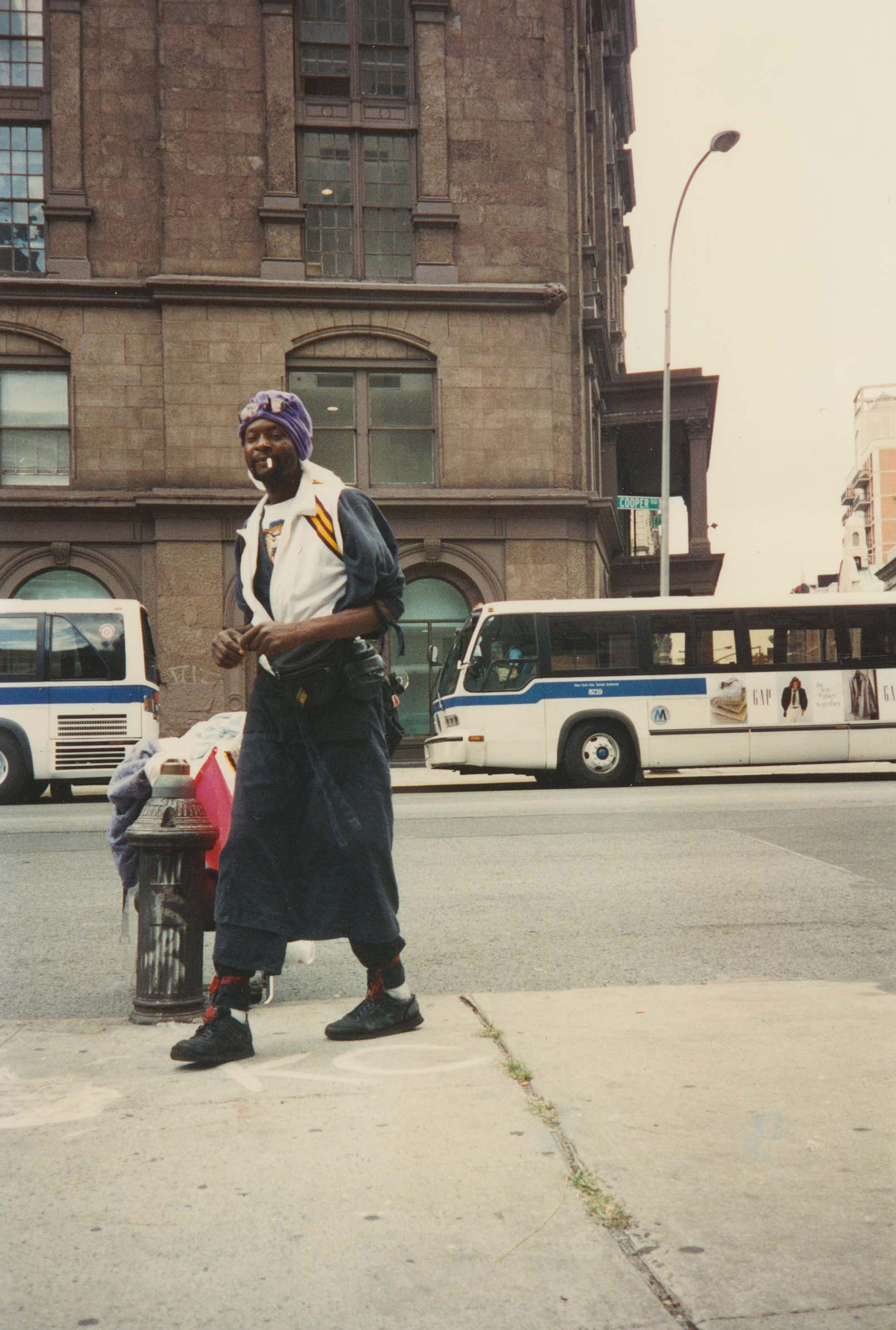

Curtis Cuffie, 1998

Curtis Cuffie sculpture, ca. 1994–96. Photo: Katy Abel

“Much of the beauty of Curtis’s work,” wrote Carol Thompson in a 2002 eulogy, “was in seeing him create it and seeing it unfold from day to day.” 1 This book, focusing on Curtis Cuffie’s public sculptures, erected and inevitably torn down across the East Village in the 1980s and ’90s, presents this beauty as it unfolded in the streets and in photographs taken by the artist himself, his romantic partners, and two professional photographers who lived in the neighborhood. Although Cuffie’s artwork was exhibited in galleries, museums, alternative art spaces, and nightclubs, his major venues were the fences, sidewalks, and traffic medians of downtown Manhattan.

“Curtis made art as a daily devotion,” Thompson continued, and though many captured his public performances on camera, none did so with the parallel devotion of Katy Abel, who took hundreds of snapshots of Cuffie at work in the mid-’90s. 2 Her intimate collection, which she arranged into dozens of albums for Cuffie’s brother Alvin and sister-in-law Peggy after the artist passed, are at the very heart of this book. Abel, born in Greenwich Village, was living in a loft on Cooper Square that she had shared for many years with her former partner, the bassist and composer Sirone (Archie Shepp and Amiri Baraka were their neighbors). For twenty-seven years she worked at the Village Vanguard, in the cloakroom, as a waitress, and as a hostess. She was not, in her words, a photographer; before meeting Cuffie in her late forties, Abel had rarely used a camera in a concerted manner. In fact, the first time she saw his work she ran to grab a colleague to take pictures of it. Upon learning that its maker was a music lover she gifted him a radio. He asked her on a date for Independence Day. As Abel described it, the events of the Fourth were like something from a fairy tale. They met at a safe distance from the crowds, which Cuffie preferred to avoid, and watched the fireworks over the East River. When Abel left to get refreshments, Cuffie converted the shopping cart out of which he lived and worked into a festooned carriage, and upon her return, himself skirted up in an array of patterned fabrics, lifted her onto its mass of pillows and blankets and rushed her down the street, singing “Happy Holiday” to the revelers.

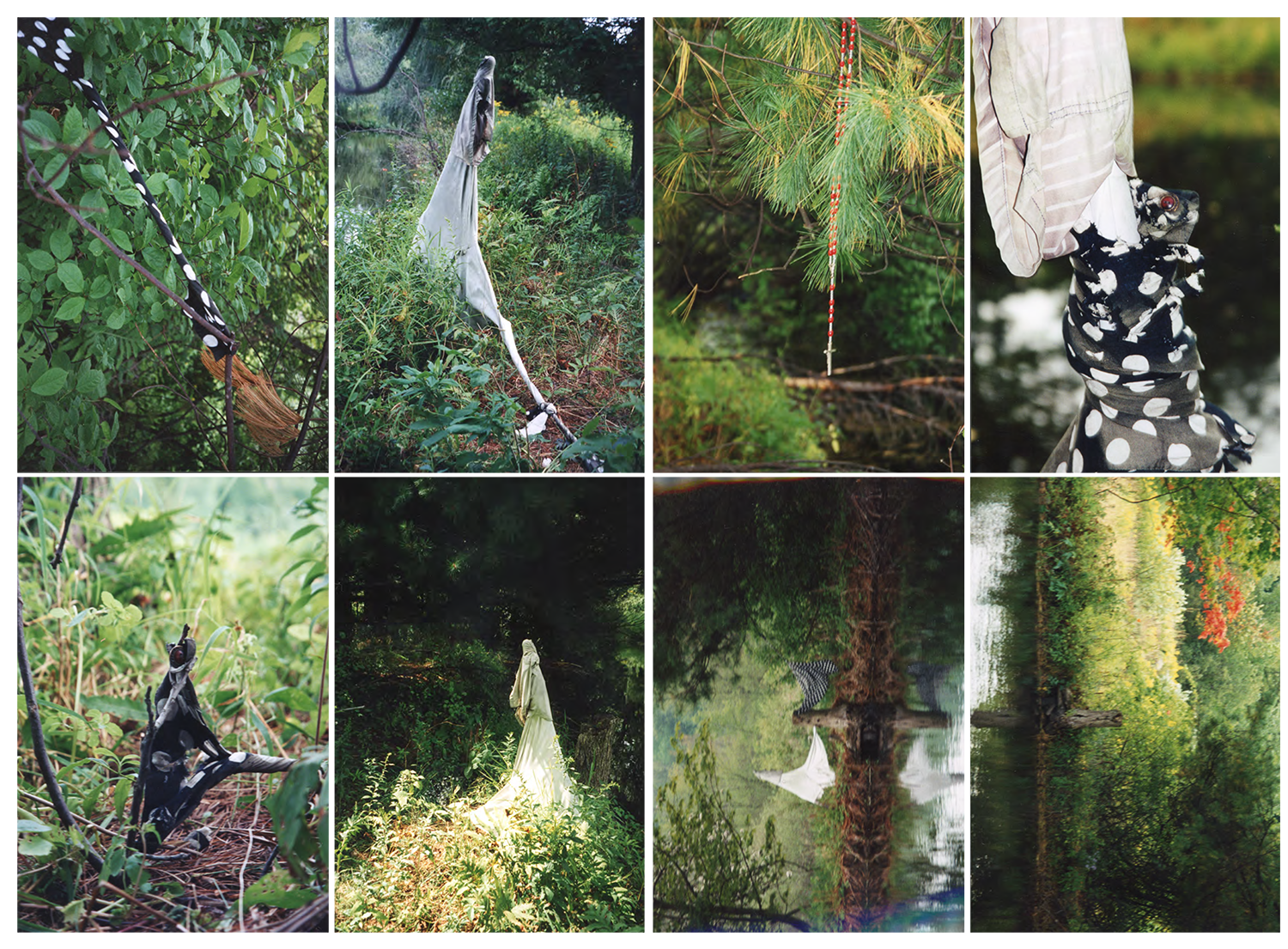

Over the years, Cuffie stayed with Abel periodically and stored a number of sculptures in her loft. She would spend hours photographing him as he worked outdoors at different locations in the 1990s and early aughts, both in the city and at her house in Eastern Pennsylvania, where Cuffie once made a sculpture at the edge of her pond to scare off beavers. To her he professed a lack of interest in preserving his most ephemeral works, but he encouraged her photography and empathized with the desire to hold on to things in perpetuity, calling her “Katy the Keeper.” 3

Cuffie sculptures at Abel's home in Eastern Pennsylvania, ca. 1994–96.

Katy Abel with Cuffie sculptures, ca. 1994–96. Photographer unknown.

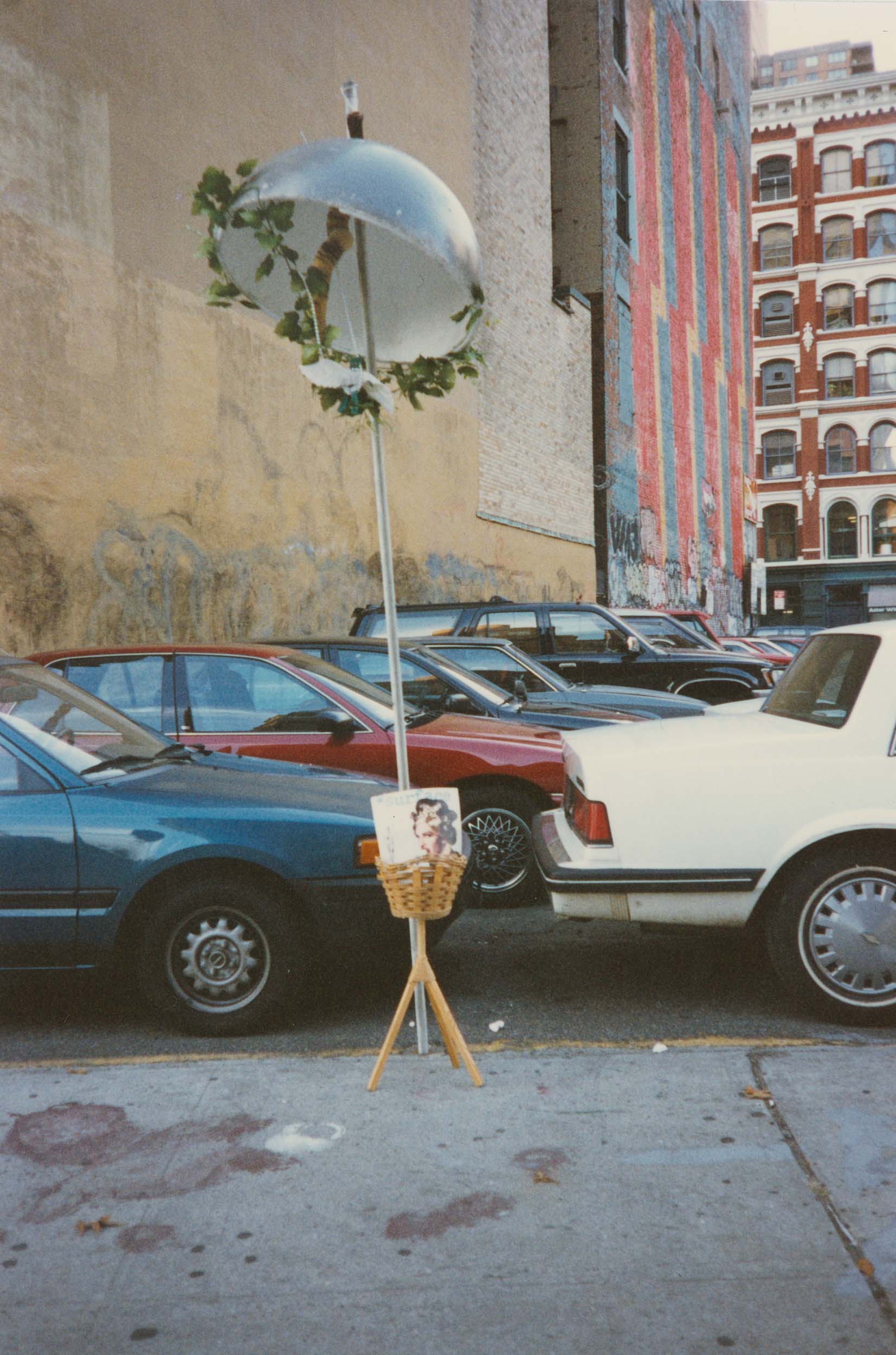

These photographs, shot in and around Cooper Square, the Bowery, and Astor Place, where Cuffie would often erect works at the edge of an unsanctioned flea market subject to near daily police raids, illustrate how the art lived outdoors unprotected from the elements. When viewed in sequence, these images have a way of spoiling the idea of sculpture’s fixity, permanence, and separability from the artist. Few of these works held place for very long; most were destroyed by law enforcement, the Department of Sanitation, or the grounds team at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Art and Science—which would go on to hire Cuffie in 2001.

Cuffie moved to Brooklyn in 1970 at age fifteen, from his hometown Hartsville, South Carolina. He told several versions of this story. In one, he was sent up north after he’d turned into a goat and started eating clothes off his mother’s laundry line. In another, he had sneaked into a local meeting of the Ku Klux Klan, seventy miles northeast of the state capital, dressed in a white robe. No harm came when he was discovered, but his family decided it was time for him to go stay with his brother Ernest, a social worker in Brooklyn. Cuffie attended John Jay High School in Park Slope before dropping out in the eleventh grade and working as a truck driver and hand laborer. He married and had three children. When his mother Jessie Bell Cuffie passed in 1983 he’s said to have entered a deep and protracted depression, losing stable housing and living around Bryant Park. 3 He relocated to the East Village not long after, where he began to make works of art in public.

Homelessness is foregrounded in nearly all writing about Cuffie, though he was himself chary about discussing it. He told Sarah Ferguson at the Village Voice that he wasn’t homeless but “holy,” and to curator Tom Patterson he described himself as “holy and free.” 4 Cuffie once remarked to Thompson on a drive home from Coney Island that the passing houses looked to him like coffins. Reportedly, he refused help accessing public assistance from his friend Darrell Maupin, owner of the East Village restaurant and club Flamingo East, where Cuffie’s first solo exhibition was presented in 1992. 5 About his living conditions, he told the Voice, “I don’t think of this—this street. There is no suffering, no misery, only love.” 6

Curtis Cuffie, ca. 1994–96. Photo: Katy Abel.

This book’s opening images were taken by Tom Warren, a countercultural photographer who participated in landmark exhibitions at ABC No Rio, capturing the early days of the East Village art scene through makeshift photo studios he set up in bohemian spaces around the city. In his images, mostly black and white and shot with a Contax T between 1992 and 1997, Cuffie’s works stand resolutely on their own as objects. Self-contained, they take leave of the disinvested landscape, estranged from the pedestrian spheres of trash and commerce on Astor Place. His approach stands in contrast with that of Margaret Morton, a Cooper Union professor who spent the 1990s documenting the homes of New York City’s homeless in the tradition of socially engaged photography. In Morton’s lens the work emanates from its environment, and is inseparable from the teeming life of the city and realities of the artist’s situation. Morton captured the way Cuffie’s “intricate assemblages of used clothing, broken jewelry, discarded toys, ostrich feathers, and advertisements would mysteriously appear and disappear on the chain link fence” across from the school at Fourth Street and Bowery. 6 She was fascinated by the work’s ironic qualities, how it made “wry commentary on the excesses of consumerism—even as it was clearly inspired by refuse and waste.” 7 It has been said that every Cooper Union student from this period knew and learned from Cuffie, whose sprawling pieces were often installed around the school’s premises. Years later Morton’s photographs of Cuffie and his art were hung in the school’s Great Hall at a memorial held three months after he suffered a fatal heart attack in his East Tenth Street apartment at age forty-seven. 8

This publication closes with a selection of photos taken by Cuffie himself. Throughout the ’90s, the artist used a point and shoot to record his art and environs on more than 100 rolls of film. These remained undeveloped in his lifetime and have been safeguarded, along with much of the rest of his archive, by Thompson, who in addition to being his partner was also the first art historian to produce scholarship on Cuffie’s work. When Thompson began this academic writing in 1996, she had left her job as a curator at the Museum for African Art in SoHo to pursue a PhD in Performance Studies at New York University; Cuffie would sit in on classes she was taking, and ones she taught at colleges across the city. He had moved into her sixth-floor walk-up on East Tenth Street that January, shortly after a historic blizzard, alternating between their shared quarters and life out on the Bowery in the early years of their relationship. Forgoing the hazards of New York City’s shelter system, he was known to set up camp downtown, above a hot air vent that he named the Sahara and would decorate with floral comforters and dried palm trees.

Curtis Cuffie sculptures, ca. 1994–96. Photo: Katy Abel

Curtis Cuffie sculptures, ca. 1994–96. Photo: Katy Abel

An artist biography Cuffie and Thompson drafted together describes his work as an urban variation on rural, Southern folk art. In this view, inspired by Robert Farris Thompson’s Africanist readings of contemporary Black American art, Cuffie was a yard artist without a yard. Unlike Joe Minter or Lonnie Holley, Cuffie owned no property. 8 His work accumulated on public and disused land: the traffic medium south of Cooper Square, a boarded-up gas station on East Fourth Street, a hurricane fence on the corner of Bowery and Great Jones. After assembling a large piece, or a procession of smaller ones, Cuffie would sell the parts, give them away, or rearrange them until being forced to move along by the police. In 1993, writer Chippy Irvine spoke with him about working in such conditions. “Every now and then, the weather—or the sanitation department—removes all of Cuffie’s works and his carts full of the beach towels, place mats, fake flowers, and menus that he uses as material. The last time it happened he was devastated, and went to church to cry. But then he started all over again.” 9

Cuffie’s sidewalk sculptures and booming voice had been in Thompson’s life since she moved to the East Village in 1988, but they became part of her daily commute when the Center for African Art relocated from the Upper East Side to SoHo five years later. They met when she heard him sing “Little Red Riding Hood” as she walked down the street in a red beret. Thompson helped Cuffie earn recognition within the East Village arts community, curating two solo exhibitions of his work at long-standing Black-owned galleries in the neighborhood. Of their working relationship Thompson wrote, “Curtis has asked me to write his words down, to tell his story, in order to help make his art, in his own words, ‘fully respected.’ He said, ‘Don’t paralyze my ego. Keep it plain and simple. I’m a country boy.’” 10 She helped write grants that won him awards and residencies from the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Pollock-Krasner foundation, and the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council. 11 They took regular trips out of town: to South Carolina and Minnesota to visit each other’s families; to Maryland to see his work at the American Visionary Art Museum. A research trip to Burkina Faso, however, was blocked by a spiteful parole officer who refused to let Cuffie leave the country over a technicality.

The first solo exhibition Thompson organized with Cuffie took place in 1996 at A Gathering of the Tribes, a space run by writer Steve Cannon at an Alphabet City townhouse he bought in 1970 using money made from his infamous novel, Groove, Bang, and Jive Around. 12 Cannon was well known as a community builder and ran his home as a literary salon until his death in 2019. Tribes, remembered by friends and younger poets as “the last crash pad on the Lower East Side,” formalized as a nonprofit organization in 1990. 13 Cannon set up a literary arts journal and a writing workshop on his stoop. “The people I knew down on the Lower East Side complained about not having any place to publish their work. . . . So I started Tribes magazine . . . Just to get them to shut up.” 14 His house would become a venue too, hosting writers and musicians including Ishmael Reed, Bill Gunn, Butch Morris, and Sun Ra. It was funded in part by donations from friends such as David Hammons, who wrote the organization’s second supporting check and gave a comment to the Times for Cuffie’s obituary.

Carol Thompson. Photo: Curtis Cuffie, ca. 1990–99

New York City garbage, ca. 1990–99. Photo: Curtis Cuffie

In the summer of 2000, Carol would curate another show of Cuffie’s work, “Heaven is Under Your Feet,” at 4th Street Photo Gallery, an unassuming storefront rented by South Carolina–born artist Alex Harsley on East Fourth Street and Bowery. Harsley opened the space in 1973, two years after starting the nonprofit organization Minority Photographers, Inc., as a place to congregate and exhibit. In a video Harsley made of the opening, a saxophonist plays amidst an overgrowth of sculpture; the word “LOVE” is written on the wall in shaving cream. 14 Harsley knew Cuffie from the neighborhood and took photos and footage of him making work near the gallery. In one recording made along the wall of the Bowery Bar, the artist spins quickly, tosses the lid of a coffee tin high into the air, spins again, and catches it. He would send these discs into traffic and dodge the oncoming cars. “The name of the top is flying medicine,” Cuffie wrote in a note dated July 12, 1997:

First, I learned it releases me from being lonely and confused. Three more reasons for the top: confused, angry, bored. It cures my confusion, it entertains my boredom, it takes away my anger. Put it this way, it is like meditation but in action.” 15

Cuffie’s risky antics, loud singing, and Delphic interviews all shaped his public persona. When the pair moved in together Thompson sought professional help for him. Following a period of psychiatric assessment, a doctor suggested to her that he suffered not from schizophrenia, as many had assumed, but from addiction to crack cocaine. In the wake of this realization, Thompson’s writing on Cuffie shifted. Unlike the art-historical and local-color profiles he had received in publications such as Raw Vision and Art & Antiques, she adopted a new, political approach rooted in cultural studies and anti-colonial history. His varied public personalities, relentless generosity, twisting moods, and nearly animistic conceptions of the objects he would find and rearrange, then, were defenses against the difficulties of life on the street, a kind of non-ceremonial spirit possession mediated by the narcotic—an Americanized version of the Hauka movement. His hardships, which manifested in his erratic comportment and ethereal work, were being compounded by the Ronald Reagan and Rudy Giuliani administrations’ wars on drugs. Cuffie got sober the following year.

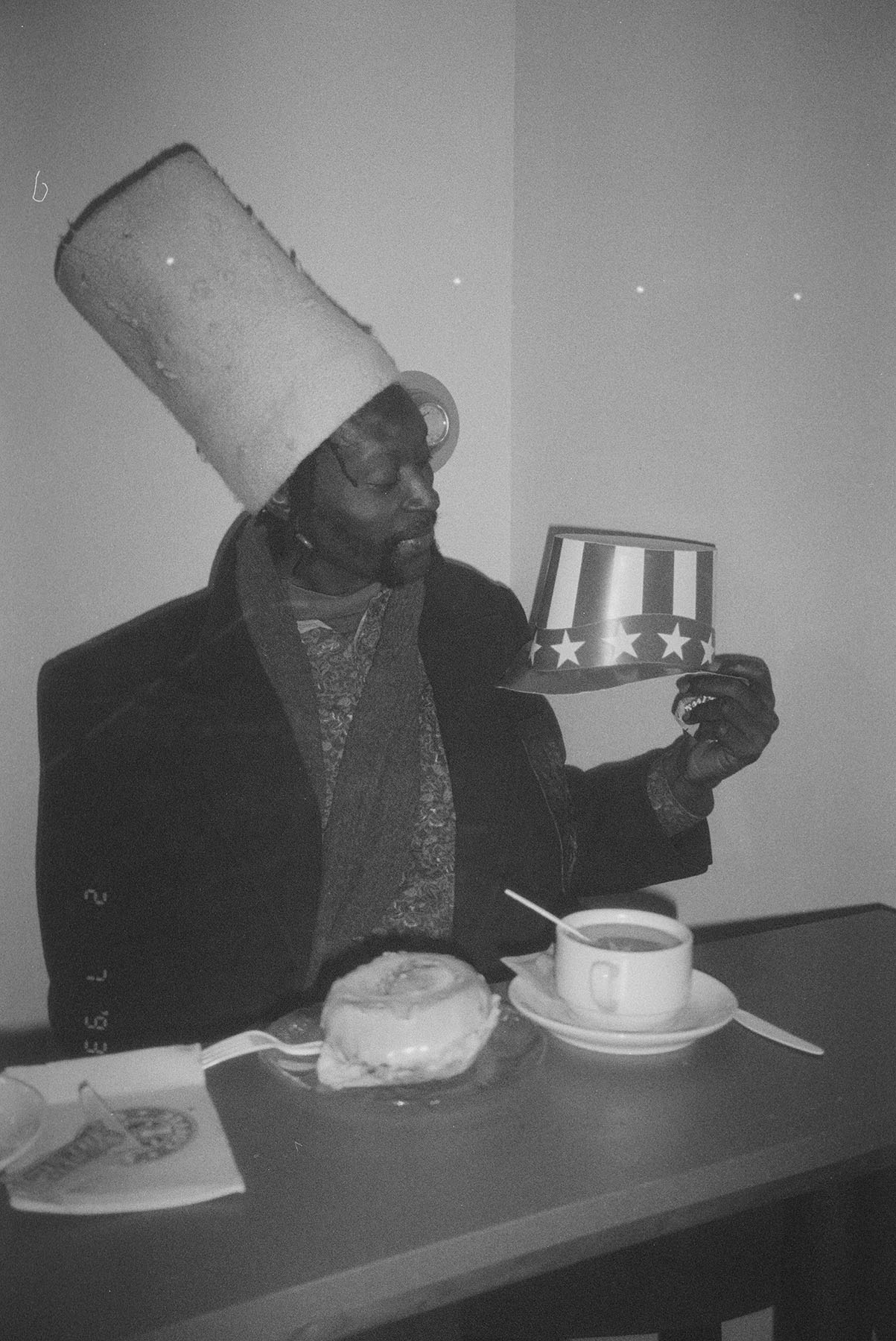

Curtis Cuffie, ca. 1990–99.

Curtis Cuffie sculptures, ca. 1994–96. Photo: Katy Abel

“Once when I walked by, Curtis was standing facing the wall with arms and legs splayed wide, all the while talking loudly to himself as though being arrested by an invisible policeman,” Thompson writes. 15 Between the ages twenty-one and forty-two Cuffie was arrested thirty-one times, primarily for gambling (he played three-card monte) and drug possession. Though he rarely discussed this aspect of his life even with close friends, it’s expressed in the titles of works such as Flag with Handcuffs for the Fourth of July, 1996.

Kenny Schachter, who organized the 1992 Flamingo East show with Maupin, and who from 1991 to 2000 included Cuffie in many buzzy group exhibitions alongside the likes of Sanford Biggers, Rachel Harrison, and Vito Acconci, once appeared in an issue of the Sunday Times holding a Cuffie sculpture beneath his arm. The caption, which identified the work as “untitled,” upset the artist. “All my works have titles,” he said to Thompson, though most often they were bestowed the moment he parted with a piece. 15 Absent titles to guide them, most visitors to his public installations would have been in the presence of the artist, who would, if he wished, lead them through a complex of allegorical narratives:

Soft-spoken, almost diffident, Cuffey [sic] offered explanations for his constructions only when pressed. . . . However, once launched into a description of a particular piece he would literally follow the thread (or ribbon, string or wire) of his thoughts from one three-D tableau to another. . . . He moved along the sidewalk—his creations stretched along a good 30 feet—and showed me “the kitchen of a reckless life.” He banged a few of the cheap ruined sauce pans he’d hooked onto the fence and touched a tattered black negligee, which inspired him to comment “too much sex.” Next to it, he said, was the “wife going off on her own.” As he spoke, he pointed to the kind of shoulder bag that’s given away at trade fairs and conventions. Blaring on its side in big white letters were the words: Service Business Success. . . . A foot or so away was “the president’s phone,” a partially disassembled touchstone desktop model neatly installed beneath a large photo of Reagan.” 16

US presidents recur across Cuffie’s interviews and imagery. In particular, Abraham Lincoln, whom Cuffie revered—he traveled with Abel to see the memorial in DC—and Ronald Reagan, ambiguously referred to by Cuffie as the “General.” 17 Related to the latter, Cuffie often discussed his own work in salvific tones occasionally portraying himself as sort of ’80s evangelist (he once told Sarah Ferguson that he traveled to New York “with Johnny Cash’s ministry,” which was aimed at those struggling with substance abuse, to run a spiritual recycling program under Reagan). 18 The former president figures not only as a symbol of contemporary faith but as the architect of modern homelessness. Under his administration, the department of Housing and Urban Development had its budget cut by nearly seventy percent. That same period saw the broad introduction of mandatory sobriety as a prerequisite for access to public housing. 19

Curtis Cuffie, ca. 1994–96. Photo: Katy Abel

Curtis Cuffie sculptures, ca. 1994–96. Photo: Katy Abel

Curtis Cuffie sculptures, ca. 1994–96. Photo: Katy Abel

The social crisis these policies induced and its effects on the lives of artists are the subjects of much of Alan W. Moore’s writing. A 1992 essay by Moore that Cuffie once commended as brilliant closes out this book. It details the successes and shortcomings of the downtown scene’s efforts to support the artist’s life and rise to the challenge of his work. 19 At this time, Moore had been writing for Tina Anton, whose nonprofit Art on the Edge distributed art supplies to homeless shelters and exhibited and sold the resulting work, and whose commercial gallery, co-run with her husband Aarne, focused on self-taught artists. Moore was also researching Hope Sandrow’s Artist and Homeless Collaborative, an initiative at a women’s shelter connecting well-known artists with residents to work on public projects; John-Ed Croft’s squatted art gallery Chocolate Milk, which showed and sold art by the unhoused; and a theater troupe operating in an encampment beneath the Manhattan Bridge. Moore was himself a member of Collaborative Projects, a democratic artist group that squatted buildings for exhibition space and made polemical, collective work addressing the real estate industry.

In light of this historical interest in art by and about the homeless highlighted by Moore’s work, Cuffie’s sculptures should be understood not only in terms of their plastic inventiveness—their celebrated contributions to radical assemblage and found-object installation— but within a continuum of East Village contemporaries that includes its squatters, hardcore musicians, and art activists; the community of homeless artists that brought Cuffie to the attention of gallerists; an older generation of Black avant-gardists, and the heady post-conceptualists of lower Manhattan. 20 This confluence structured the downtown scene in which Cuffie’s work was first received and provides the context in which it should be understood today. Inspired by the motto engraved in the cornerstone of the Salvation Army Bowery Corp., “Dedicated to the Service of God and Humanity,” Cuffie regarded his work as his mission. 21 He was gathering lost souls on St. Mark’s Place and offering them a chance at reincarnation; giving mistreated objects new life through elaborate tableaux of dissolution and salvation. But the work is equally concerned with history, intervening on that centuries-old byway of social murder known as the Bowery. In his expressive recasting, the street’s disjecta membra become delicate, suspensive constructions “in which a car is no heavier than a straw hat” and no more precious. 22 Cuffie’s art, surviving mostly in memory and in these photographs, transgressed the rule of property and transvaluated poverty, both the artist’s and the world’s, confronting Manhattan’s deprivations through its own vagrant, transverberative life.