Still from Curtis and Ma, creator and date unknown, video, color, sound, 34 minutes. Courtesy Katy Abel

These videos made available in conjunction with Curtis Cuffie, the first book on the titular sculptor, offer two views of Cuffie’s work: a public access broadcast situating the artist in the broader New York scene, but struggling to make him legible, and an intimate moment captured by film students, where he works with his partner Katy Abel beside him.

Curtis and Ma

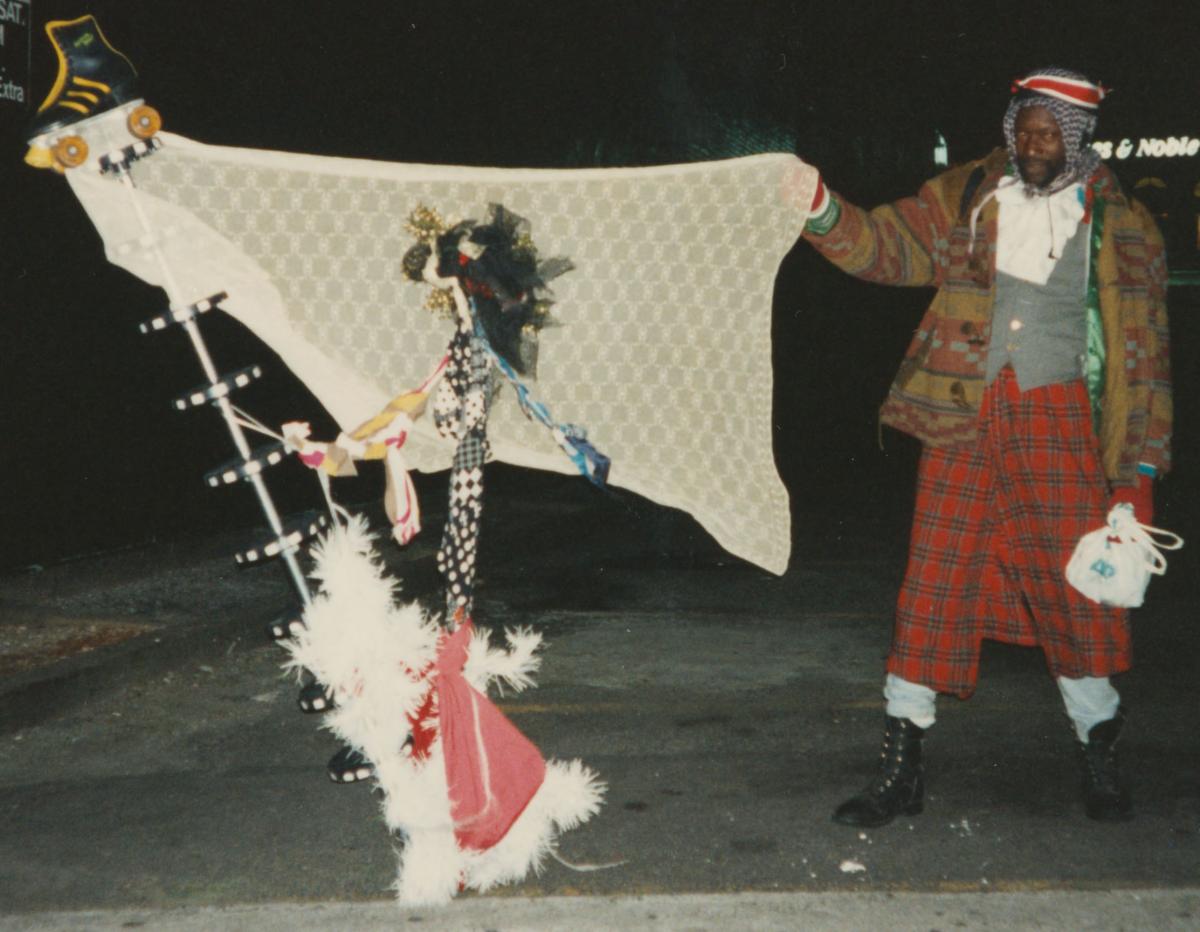

In the opening shot of this unseen videotape, Katy Abel kneels on Astor Place near Tony Rosenthal’s Alamo, 1967, photographing Cuffie’s work. Titled Curtis and Ma, this VHS from Abel’s private collection was created as a school project by unidentified New York University students, documenting the tender interplay between Cuffie and Abel. We glimpse both their relationship and the social situations that produced the bulk of the extant images of his art—street photographs that Abel compiled into albums and gave to members of Cuffie’s family at the memorial held at Cooper Union’s Great Hall, one block from the Cube, after he passed in 2002.

A street performer plays a flute as Cuffie dashes to and from a cart containing his raw materials, black families stroll the sidewalk, and passersby ham it up for the film crew. The camera lingers on Cuffie, who politely redirects the attention of its operator—“Katy, not me,” prompting Abel to speak about their relationship. “His stuff was always being taken down,” she says, “I’d go to the store and there’d be a beautiful display. By the time I got back everything would be gone, you wouldn’t see him for weeks.” Moved by the sight of his installations, but without prior experience as a photographer, she was convinced that her pictures might nevertheless help to preserve the work and support the artist, hoping “to try to just stop him from being harassed here.” Abel also speaks about trying to take Cuffie on a trip to Mexico, but being unable to locate his paperwork.

The video provides a rare instance of the artist on film and presents the work as viewers in Cuffie's lifetime might have seen it, in the presence of the artist, who would toss plastic lids into nearby streets and catch them amidst oncoming traffic, or might activate the environmental sculptures with commentary and narrative. In 1991, Phyllis Orrick described the soft-spoken Cuffie improvising these ad hoc artists’ statements in the New York Press, "as he did so, the internal iconography and symbolism became ever more compelling and more—for the moment at least—logical in the way that nonsense (and madness) can be.”

Cuffie’s persona as a madman or street preacher is one he seems to play with in this recording, where his free-flowing monologue leaps from verbal puns to biblical verse. After plucking a detail from the tall sculpture beside him and making the cuckoo motion, Cuffie addresses the camera, “My name is Paul Simon and I’ve got a problem.” Abel chides him to the director—“And this was after I told him you wanted him to keep the clowning down.” After an oration touching on housing, schooling, and Ronald Reagan, Cuffie eases into an impromptu sermon, sliding between speech and song: Thank God for the plum, and the prune. And thank God for the pig . . . Let’s give pigs a chance, man. Thank God for hibernation, reincarnation. Thank God for still crazy after all these years.

City Arts

This brief profile, showing Cuffie at work outside the Village Voice office, comes from an episode of the half-hour culture roundup City Arts, which aired weekly on New York’s Channel Thirteen. In this clip—made on the occasion of Cuffie’s inclusion in the Art on the Edge booth at the 1998 Outsider Art Fair—Artforum contributor Jennifer Borum describes what it means to consider his work in this category: “These are not career artists, they’re not trying to make a career. Curtis Cuffie makes things because he has to make things.”

Cuffie is profiled alongside embroiderer Raymond Materson, who speaks about serving a fifteen year sentence for armed robbery, and Ralph Fasanella, a working-class painter and union organizer who, like Cuffie, spent time as a truck driver before committing to his art full-time. Tina White, the director of Art on the Edge and one of Cuffie’s earliest institutional supporters, describes him as an environmental artist whose “constructions are meant to be outdoors and free.” She views it as her task to find the elements that can work indoors as standalone pieces, to be preserved or sold on his behalf. Cuffie is not interviewed, but shown gathering materials and adjusting his work in a red patterned bathrobe, tulle scarf, white headwrap, and respirator. A man on the street stands beside him and offers his thoughts: “People come and take stuff. It’s something that they would have seen in the garbage and never appreciated, until they see the way he displays it, then they take it. Ain’t that crazy?”

Text by Ciarán Finlayson