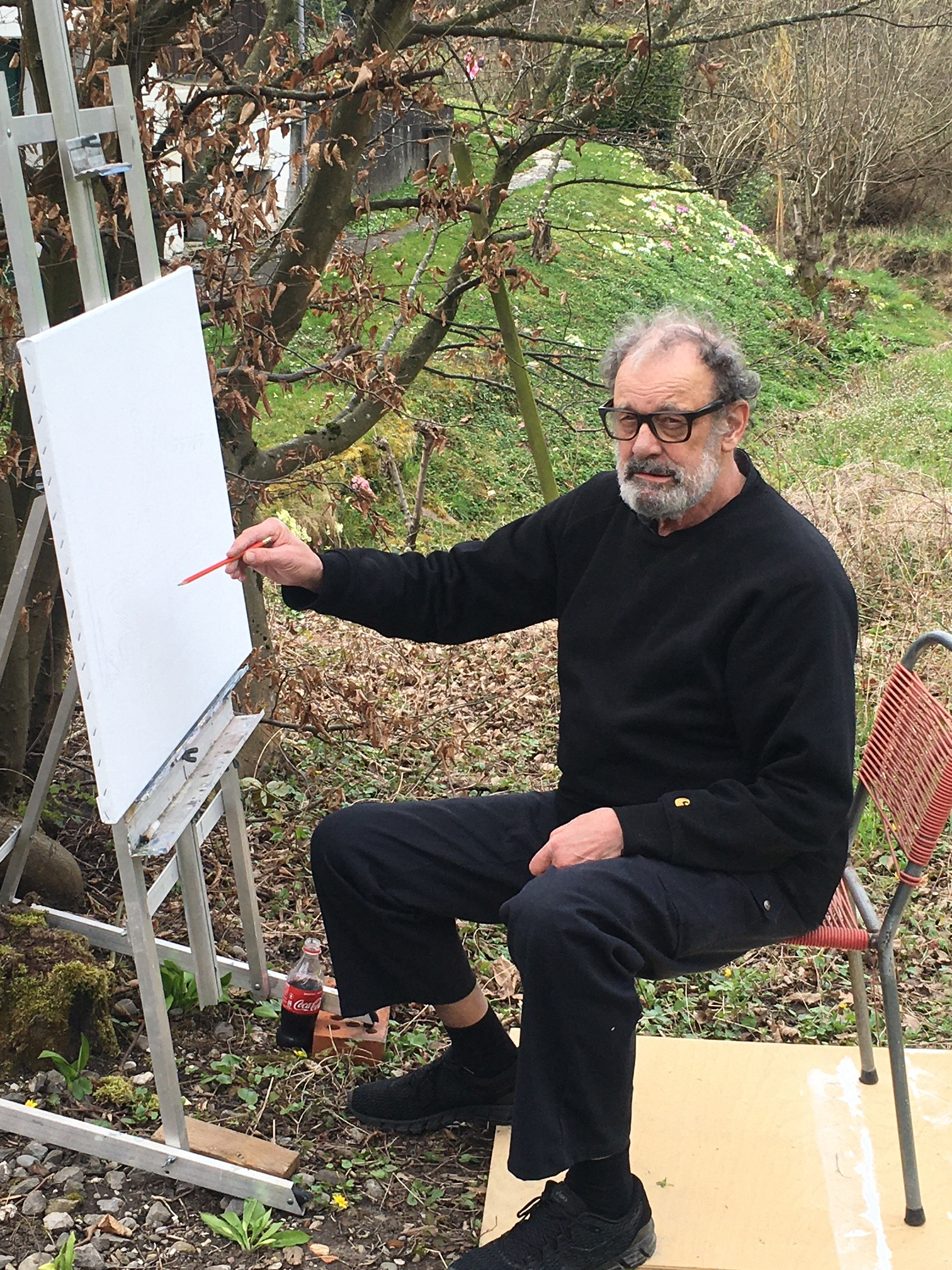

Anton Bruhin in his Zurich studio.

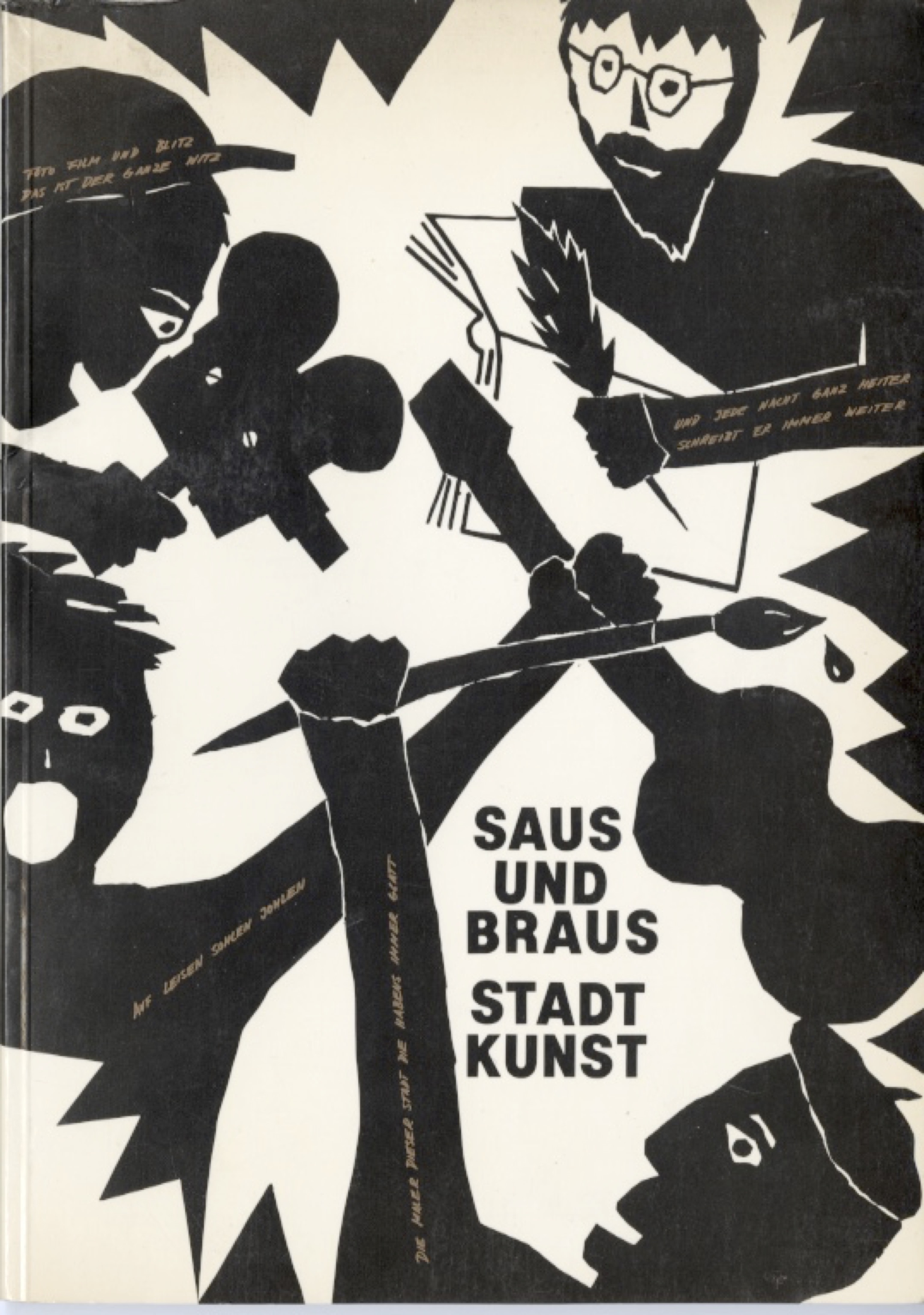

HANS ULRICH OBRIST: Perhaps it would be interesting to start at the beginning. The first time I saw your work was in connection with Bice Curiger’s exhibition “Saus und Braus” (Living the high life). It was before my time—I was only twelve years old when the exhibition took place—but at fifteen I obtained the catalog. Yet there must have been earlier works, from the ’70s and so on. How did it all begin? How did you come to art, or how did it come to you? Was there some kind of sudden awakening or epiphany—a specific experience?

ANTON BRUHIN: At an early age I was allowed to play in my father’s office, even with the typewriter. I took an interest in the letters. At first it was their essential shapes, with these tips or bellies and everything else that letters have. And then came drawing and writing and maybe singing little songs, as a child does. It could be that I pursued this a little more intensely than the average person, but there was no predetermined reason—an upbringing in art, for example. For my family, the highest form of art was a Bible with illustrations by Rembrandt, Titian, and others. That was more or less it.

HUO: What did your parents do?

AB: Father was a miller; mother, a housewife. She liked to decorate everything: wall covers made of burlap and felt, beautiful little pictures, a wonderful case for badminton rackets with a zipper and felt shuttlecock on it, and so on. That was the joy of creating.

I grew up in the country, in the March District in the canton of Schwyz—not exactly a musical area. Father played first violin in the Tuggen Orchesterverein (Tuggen orchestral society), but otherwise it was a desert: Art was and is highly suspect.

My parents collected my childhood drawings, however, and dated them on the back. This was a form of recognition for me, and I still thank my deceased parents today for mustering this attention to my little works. That was instrumental.

HUO: Were there any significant early encounters with works—or with heroes?

AB: In 1954, my parents built a house. We moved in; then furnishings, such as carpets and the like, followed piece by piece. Among them was a pair of oil paintings. One day, an artist with a mustache, beret, and Gauloises arrived in a Döschwo (Citroén 2CV). He brought a few paintings with him—landscapes, a little better than true kitsch: reedlands, boats in the harbor, etc. He stuck them here and there on the walls. As a five-year-old, I touched the canvas with my fingertips to see if the paint had dried yet. This would have been the divine spark that set me on the path. That was when I first consciously realized, “I want that, too: Döschwo, stache, beret, Gauloises, and all.”

HUO: You attended the Zürch Kunstgewerbeschule relatively early on. Is that where you met David Weiss?

AB: I hadn’t encountered David yet at the Zürch Kunstgewerbeschule; that happened a little later. I was in the same class as Walter Pfeiffer and the late Christian Rothacher, an artist from Aargau. He made beautiful things. For example, he painted a night train on a neon tube. That was only in the second year of the new Class F+F (Form und Farbe).

HUO: Was he part of the scene around Hugo Suter? All of a sudden there was this movement in Aargau in the ’60s.

AB: There were a few of them in Aargau: Hugo Suter, Max Matter, and Heiner Kielholz, the quietest of all of them and arguably the most profound.

HUO: Art schools don’t really work, as a general rule. One can’t teach art. On the other hand, sometimes there are such fruitful communities as the Black Mountain College. The Zürch Kunstgewerbeschule, or so we often read, seems to have been a very interesting environment in the ’60s. There was something in the air. How would you describe it?

AB: It was the era of Pop, Beat—a time of transition. You waited for the latest Beatles or Stones album to be released, then you ran out and bought the record. That’s how it was, at least in the West. At the Zürch Kunstgewerbeschule, I spent a year in the preliminary course, which was still somewhat tame and old-fashioned. But I saw interesting-looking students in the corridors, and they were all from Class F+F, so I took that class the next year. Serge Stauffer and Hansjörg Mattmüller were the two teachers, and they were excellent; I felt I learned more that year than in my entire time as a student.

It was a time of awakening and economic boom. Of course, every generation has the feeling that they invented something new, but back then a few things really did come about which hadn’t existed till then. Flower Power, drugs, “turn on, tune in, drop out.” People met on the Zurich “Riviera” to let their hair grow. Everything was steadily trending up; one didn’t have to worry about anything. One could always find a job with a decent salary in a pinch.

This soon changed. At the time, in the West, Pop Art was the order of the day—the latest dominant art movement. Then it began to split into Op Art, Land Art, Conceptual Art, and all that followed. This eclectic era continues to this day.

HUO: How would you describe Stauffer’s influence? I’m told he was a Duchamp expert, had engaged with poetry, and brought together a wide variety of art forms. He was often described to me as something of a Renaissance figure …

AB: … defined by universality, yes, by totality. It was 1965; I was quite young. I was simply interested in cool products: beautiful paintings and exciting art. I didn’t understand this holistic aspect of Serge Stauffer at the time; I didn’t ask myself questions about it. No, it was just Serge. In conversation, he always gave you the feeling you were on an equal footing. I thought he was brilliant and humane. He wouldn’t get harsh when someone came to him with weird pubertal problems, as I was used to from other teachers.

Rudolf Frauenfelder, whose preliminary course I attended the year before, also addressed us students as equals and, like Stauffer, encouraged perpetual learning. Frauenfelder knew how to guide us toward both unexpected perspectives and fundamental explanations, and he did so largely outside of the established canon, with a radical lack of arrogance. Serge opened up remote sites of discovery for us and allowed us to recognize the strangeness of the banal.

HUO: How did you arrive at your first works—or, when did your student days come to an end? Put another way: If someone were to make an index of all your work—a catalogue raisonné—what would be first on the list?

AB: The transition from a playing child to a still-playing teenager was seamless. The conscious stage—“I too want to become a painter”—came by touching a painting with my fingertip, as I mentioned. The childlike motive was probably to imitate that painter like one monkey imitates another.

Or—not quite. Rather, I would say: It was less an imitation than a wish. An “I, too” wish. Not “to act like” someone, but “to be, as well.”

As for when and where exactly was the moment when I said to myself, “Now it’s the real deal; till now it had just been student work”? I don’t remember such a point. The feeling that I was seriously doing something—making art—was there very early on, at the latest in the Zürch Kunstgewerbeschule.

I still have drawings from childhood and works I made as a student. The former I would have to search for, but my works from school are around. I don’t think there’s anything great there.

But this question of inflection points makes me think about the primacy of Pop Art at Class F+F. After Malevich’s black square and Duchamp’s bottle rack, a point of no return was reached. The world was divided into before and after.

I wanted to paint and was irritated that we weren’t allowed to. The aim was to achieve an “industrial” surface. If it smelled like turpentine, it was scoffed at. Above all, you weren’t allowed to use brushes—the closest you could get was spray paint. Recognizable craftsmanship was frowned upon. This preoccupied me at the time with philosophical intensity. I came back from summer vacation with two, three small plein air landscapes, and I could already see how my fellow students would react: “Oh, here he comes again with all that stuff …” Not that I wasn’t also interested in Pop. But it should be said that if someone was painting Pop Art in 1965, that was still considered painting—and therefore passé. This contradiction didn’t seem to matter to my contemporaries.

Soon, though, I realized that every generation thinks they’ve invented “it,” but there were advanced civilizations in the middle of Africa that were making bronze heads centuries ago that are almost photorealistic. There was an exhibition in Kunsthaus Zurich, “The Art of Black Africa,” in 1970 or ’71, with all this centuries-old work that looked extremely modern …

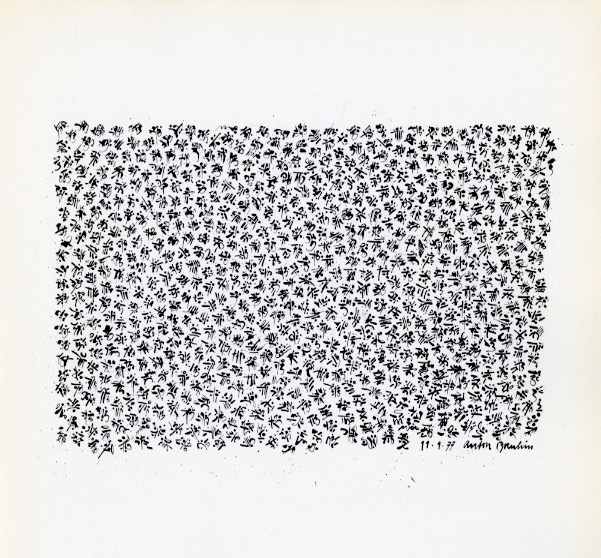

HUO: The question of what is number one in your catalogue raisonné is also the question of when your first inventions emerged. I’m familiar with your early series of calligraphic all-over drawings from 1977, which were shown at the Galerie Kornfeld. This was a discovery—a moment when you found a language.

AB: Yes, it was a discovery. With those calligraphic sheets, I was considering Henri Michaux, who drew on beautiful paper at the scale of about 50 × 70 centimeters.

HUO: So Michaux was the one who inspired these sheets?

AB: In a sense. It was more about text. I was more concerned with textures, and with the essentiality of writing, of letters themselves, that I experienced as a child. Later, I began an apprenticeship as a typesetter, so I dealt with typography for a long time. The calligraphy aspect came from school, where I was drawing and drawing. Although I painted a few pictures during my school days and then put them aside, I only became a painter in the ’80s, when the Neuen Wilden (New Fauves) came along. Actually, I had wanted to save painting for old age.

HUO: [Laughs.] When suddenly everyone was painting?

AB: For once, I wasn’t anti-cyclical. Normally I like to be a bit of a maverick. But I don’t do everything just in relation to the environment and others; rather, I have an autonomous need and drive.

HUO: Let’s come back to the reference to writing, to typography, to the typewriter, and then to Michaux, écriture automatique, and your calligraphy. How did your self-published books come about?

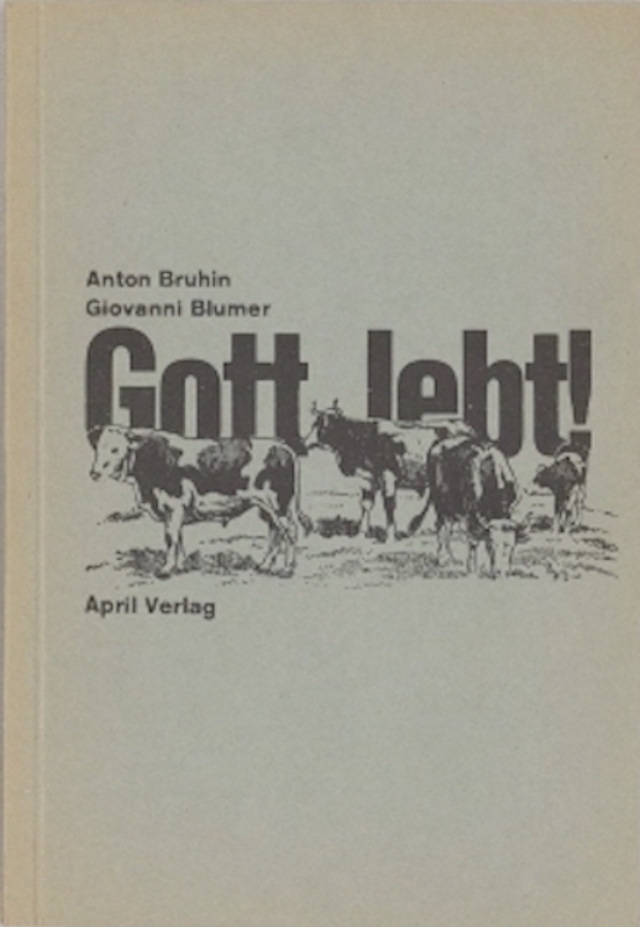

AB: The April Verlag work came out of the same interest in text and textures. I was always interested in making little magazines. As for the little books, I wanted to play editor.

HUO: Could you say something about the content of your first book?

AB: The first book was Gott lebt! (God lives!). It was all anecdotes. I spent a winter in Ticino with Giovanni Blumer, an homme de lettres. With Blumer I started playing with phrases like, “God was sitting in front of a restaurant drinking Pernod.” Or, “God went to see the movie The Bible and said ‘The book was better.’” Was I reckoning with my faith? [Laughs.] I don’t know. But strictly speaking, Rosengarten und Regenbogen (Rose garden and rainbow) was the very first book. It had mirrors on the cover and a marbled jacket, inspired by the classic design of Insel Verlag. It was set directly from the typecase, without a manuscript—as in, it wasn’t first conceived, then set and printed, but conceived during the setting itself: One letter follows the next; words and lines pile up to form a page. I find Rosengarten und Regenbogen to be absolutely hollow in terms of content. For me it was more about making a book; the text itself was filler material. In Dieter Roth’s Selten gehörte Musik (Rarely heard music), the point is that time comes to an end when the record is full. “Time must go, go, go, go, go …” There is no content; the content is nothing. And I actually feel like I’m caught in the act when you talk to me about content; there hardly is any.

HUO: It occurs to me that when I mention your name to people in the experimental music scene, they call you “a music guru”; when I tell Kenneth Goldsmith about you, he says you’re “a poetry guru”; and when I talk to artists, they say, yes, “an art guru.” It’s very rare for someone to make a contribution in all these fields. Was this always the case?

AB: Yes, absolutely, it was always like that. Drawing and painting, making music and writing texts. I don’t mix the disciplines. I’m conventional when it comes to categories; it’s part of my natural disposition. At the time, I suffered a bit from the fact that I was said to be doing a little bit of every discipline, but nothing clever. In 1975, the [Swiss newspaper] Neue Zürcher Zeitung still saw me as a “Proteus type” who could be tailored to fit any circumstance; a few years later, Woody Allen presented a vivid version of such a regrettable chameleon in Zelig (1983). I internalized the feeling that I hadn’t figured it out yet. But I couldn’t change myself to satisfy social expectations.

Now, though, I have a modest comparison for myself: Agriculturally speaking, I don’t practice monoculture. Rather, I produce wood, pork, vegetables, etc.

HUO: In the ’80s, painting resurfaced. You say that was the first time you weren’t anti-cyclical. How can one describe your painting? It’s not photo painting; it’s not Pop; it’s a very specific form of realism.

AB: I don’t concern myself with questions of style. It is figurative painting, and I do it live, by sight. I need to paint my immediate view; I don’t paint from photos or preliminary sketches.

HUO: Never? I mean, with preparatory drawings or photographs?

AB: Only to organize the composition. Otherwise it’s always plein air, always by sight. I look at the view as a score. I don’t impose; I interpret. Like a musician, I stick to the musical text. That is the main craft aspect.

I don’t deal with art questions, but I bring the hay under the roof. Whether it becomes art or not? Whether the spirit blows or not? It does, but when it wants to. One can’t just say: Today I am a little more or less full of spirit than yesterday.

In the Hirslanden Klinik, there are panoramas of the Hungarian landscape from the incredibly hot summer of 2003. You can feel a store of warmth and bliss radiating back from the pictures. The pursuit of happiness, the production of comprehensible feelings of happiness, to be experienced through the work of art—that is the most important thing to me.

My nature is not to wallow in the abysses of humanity. I am not here to mull over problems, but to provide solutions. When I meet people and they ask me, “What is your painting like?”, I say, “It’s nice.” In the past, you weren’t allowed to say that.

HUO: Wow. I didn’t know that all your landscapes—the mountain landscapes, the Hungarian landscapes, and also the cityscapes—emerged en plein air.

AB: Yes. It is so that the immediate, what I experience, can be recovered in the work: the freshness, the gust of wind through the leaves, the temperature of the light. The mood: calm or the commotion, lurking or arrival.

The work has an art historical position that it assumes, but I can’t say what it is. I give all the space to intuition. I don’t assert any approach. I’m just looking for: What is it? If the journey is the destination, then I’ve arrived, right from the start.

HUO: A good sentence.

AB: I mean exactly that. With each work, I set out in earnest from the beginning; I don’t just keep building the foundation for later on. I risk being a bit slow on the uptick, but it’s worth it.

HUO: And then there are all of your experiments with the trümpi …

AB: The trümpi is another story in itself. In 1967 or ’68, I heard and saw it for the first time on the Zurich “Riviera,” and that was it for me. Of course, that was also a major moment for psychedelic music. Around 1965, Robert Moog’s first commercial synthesizer, the Mini-Moog, came onto the market, and that was very influential.

But I realized the trümpi is also a synthesizer: In both, you filter out the overtones. You only subtract, and you don’t need to add anything; it works right away. The instrument was a bolt from the blue. And it struck.

HUO: You have a whole collection of trümpi, yes?

AB: I have over a thousand. [Points.] Here are all the trümpi. Here are the international ones, all the different provenances …

HUO: Sorted by geographical origin?

AB: Yes. Here are the international ones, and here are my concert instruments: my trümpi by Zoltán Szilágyi, my Stradivarius from Hungary. If you have a chromatic set of every model over two and a half octaves, pretty quickly you have a few hundred.

HUO: How do you create scores? In your album deux pipes (2010), there are not only drawings, but also scores with umlauts, diphthongs, vowels—almost like poems.

AB: The answer requires basic knowledge of the trümpi’s acoustic properties: The spring of the harp produces a single undertone. Its overtones can be filtered out through different positions of the mouth cavity, thus suppressing the other partial tones. An open, large oral cavity, as in the pronunciation of the letter “o,” produces low overtones. A small, tapered oral cavity, like when pronouncing the vowel “i,” renders the highest overtones. All overtone sounds and melodies are formed exclusively by the mouth organs: tongue, palate, teeth. They don’t come from the vocal cords. For overtone melodies, the prevailing notation will do; for phonetic and tonal subtleties, I don’t know of any written system. In “Trümpi and Speech” on deux pipes, the sounds are based exclusively on vowels, umlauts, diphthongs, in which case the score can be transcribed in the alphabetic writing system. These arrangements of letters almost automatically take on a poetic charge.

HUO: Your experience of music with the trümpi leads us to the poems. How did you come to writing?

AB: In secondary school I first heard a palindrome that fascinated me, so I began to pick out letters of my own, like “SAU AUS USA” (son of a bitch from the USA). As soon as I was at the Zürch Kunstgewerbeschule, we were introduced to the work of Ernst Jandl; Anastasia Bitzos gave a lecture about it. That was impressive. Jandl is immortal. Emmett Williams too.

HUO: Williams told me about this performance of yours in Zurich in 1996, where the trümpi popped up …

AB: Yes, with Marlene Frei. The collaboration with Marlene Frei came about organically. Emmett had a performance in the hall of the Museum of Decorative Arts, Out of Africa. He sat down at a table, took something flat and black out of his pocket and began to inflate it slowly. It soon became clear it was a plastic gorilla. It gradually filled with Emmett’s breath and straightened out, bit by bit, until it was firm, sitting on the table at eye level with Emmett. After pausing for a moment, Emmett slowly let the air out of the gorilla, and the ape gradually collapsed. It took a while for the plastic to flatten so it could be folded neatly back into the bag.

Emmett invited me to appear on stage at a certain point in his performance and play two or three pieces on the trümpi—concurrent with, but unconnected to, his act—and then to leave the stage again. The ape made such a big impression on me that the next day I made the monkey skull titled Schematoid. The day after I built a skull with wooden sticks: half-ape, half–prehistoric man. I thought of Lucy, as in the fossil, and I dedicated the object to Emmett Williams.

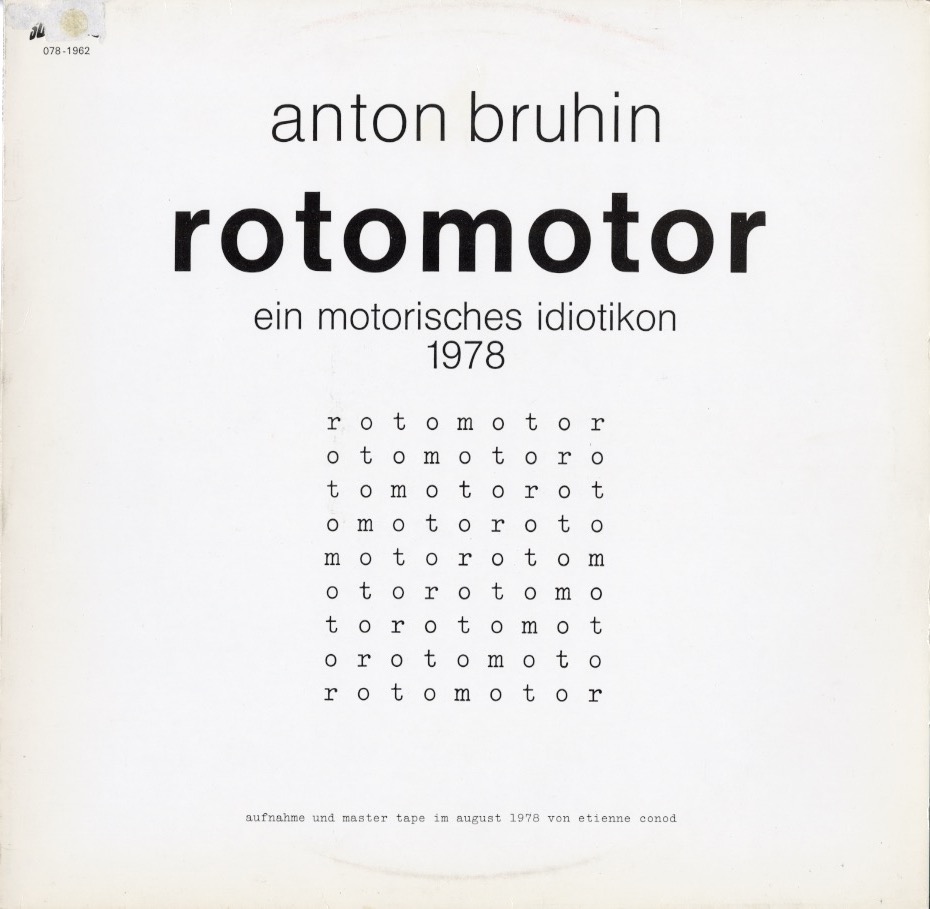

HUO: But—to return to the poems—rotomotor (1978) fascinates me very much. I’ve heard it over and over again—both the High German version and the Swiss German version on the internet. rotomotor reminds me of the work of the Oulipo writers in France …

AB: Yes. It’s a dictionary where the words are not arranged alphabetically, but according to their phonetic neighborhood and their letter sequence. Each word differs from the next by just a single letter, which is added, removed, or replaced by another. I wasn’t thinking of Oulipo, though; I just learned that such word series were a popular parlor game in England at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

HUO: Then we have your mirror poems—palindromes. Your first book of mirror poems is from ten years ago. Was there a connection to André Thomkins?

AB: Actually, I didn’t get to know Thomkins until art school. Even then, I didn’t get started on mirror poems until much later. I tried for years, but I couldn’t get beyond “Gras-Sarg” (grass casket) or “Marktkram”(market stuff)—not a word, nothing. It was only in 1991, after Thomkins’s death, that I managed my first palindrome, which I wrote by hand. Then, in 2000, I typed up my existing manuscripts, and that triggered a torrent of palindromes. After that, I started using a computer.

For a long time I thought I had invented the nonsense palindrome “Planetoid Idiotenalp,” but Thomkins had beaten me to it. Someone from Berlin came across “Retsinakanister” (can of retsina), without knowing I’d also come up with this word. But it’s stupid to wonder who was first after the fact.

HUO: Are there any projects that were too big or too small to be realized? Self-censored projects, forgotten projects, projects that were too expensive, lost competitions? I’m very interested in the whole category of the unrealized.

AB: Am I supposed to sing the praises of unhatched eggs? I’ll boast when the time comes. In any case, I’ve had enough input that I could now be locked in a cage with a computer and a pencil for life and I would certainly never get bored.

HUO: How has the computer changed your work? It seems to have played a role in your drawings for the last few years; how did that start?

AB: With copy and paste, drag and drop, and such functions. It’s great—you only have to draw a pixel figuration once, and then you can multiply and mirror it.

HUO: But that’s the next stage—the pixels were first. How did you get started with pixels?

AB: Oh, that was before the computer. I was interested in music boxes and carousel organs that are played with punch card leporellos. Digital control systems were used long before electronic computers; you’d turn them on or off pneumatically, or mechanically, and later also optically. Automated looms had existed long before that too. The first computers used punch cards for graphical conversions. Before digital pixels on a liquid crystal screen, there were physical analogs: small units of function, organized into an array.

HUO: How important are pre-digital technologies for you, compared to digital ones?

AB: The Kreuzstich—embroidery with cross-stitches—is at least as important as the digital pixels. For me, it’s about reducing information. How few pixels do you need to make a figure legible? Such minimalist architectures have existed for thousands of years, in archaic textile patterns from Central American, African, or Slavic peoples, ceramics, mosaics …

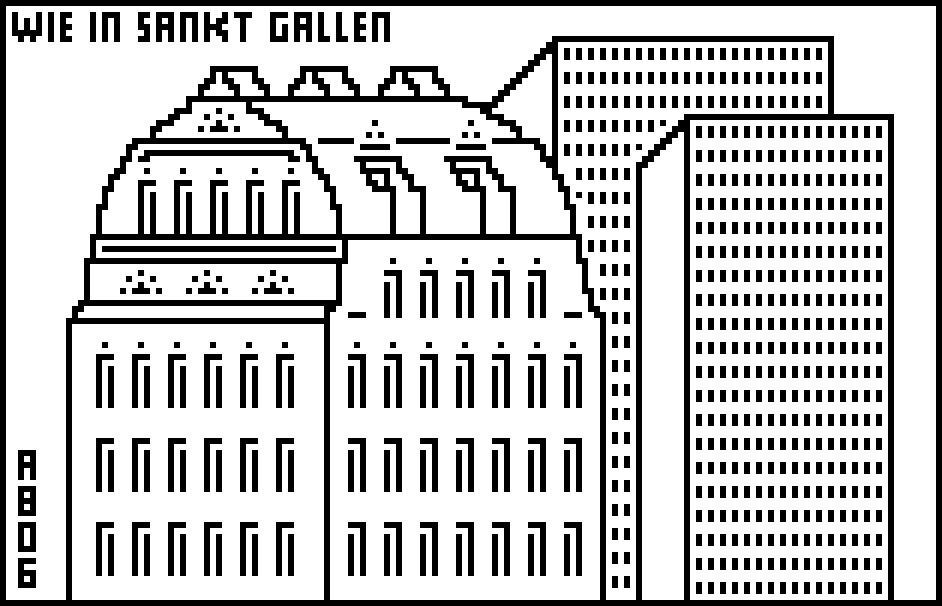

HUO: Sometimes your pixel images deal with generic motifs, but some are of cities; I saw St. Gallen, for example.

AB: In my silkscreen print series, Hice for Weiss (2012), the subject was houses. I was supposed to make a logo for the company Projekt Interim. I delivered the pixel building quickly; within half a year, I had produced more than a thousand additional drawings.

HUO: How did you start assigning them to places—Rome, St. Gallen, etc.?

AB: They’re more “ideal landscapes” than real places. That’s why I title them with “As in …” I have As in Rome, As in St. Gallen, As at Lake Walen, As in Belgium, etc. In Goethe’s time, people practiced “copy and paste” when rendering landscapes; they would include a bit of Greece here, a Roman ruin there. They collaged scenes from real or invented motifs.

HUO: I like that. Landscape as copy and paste.

AB: It’s nothing new in the West.

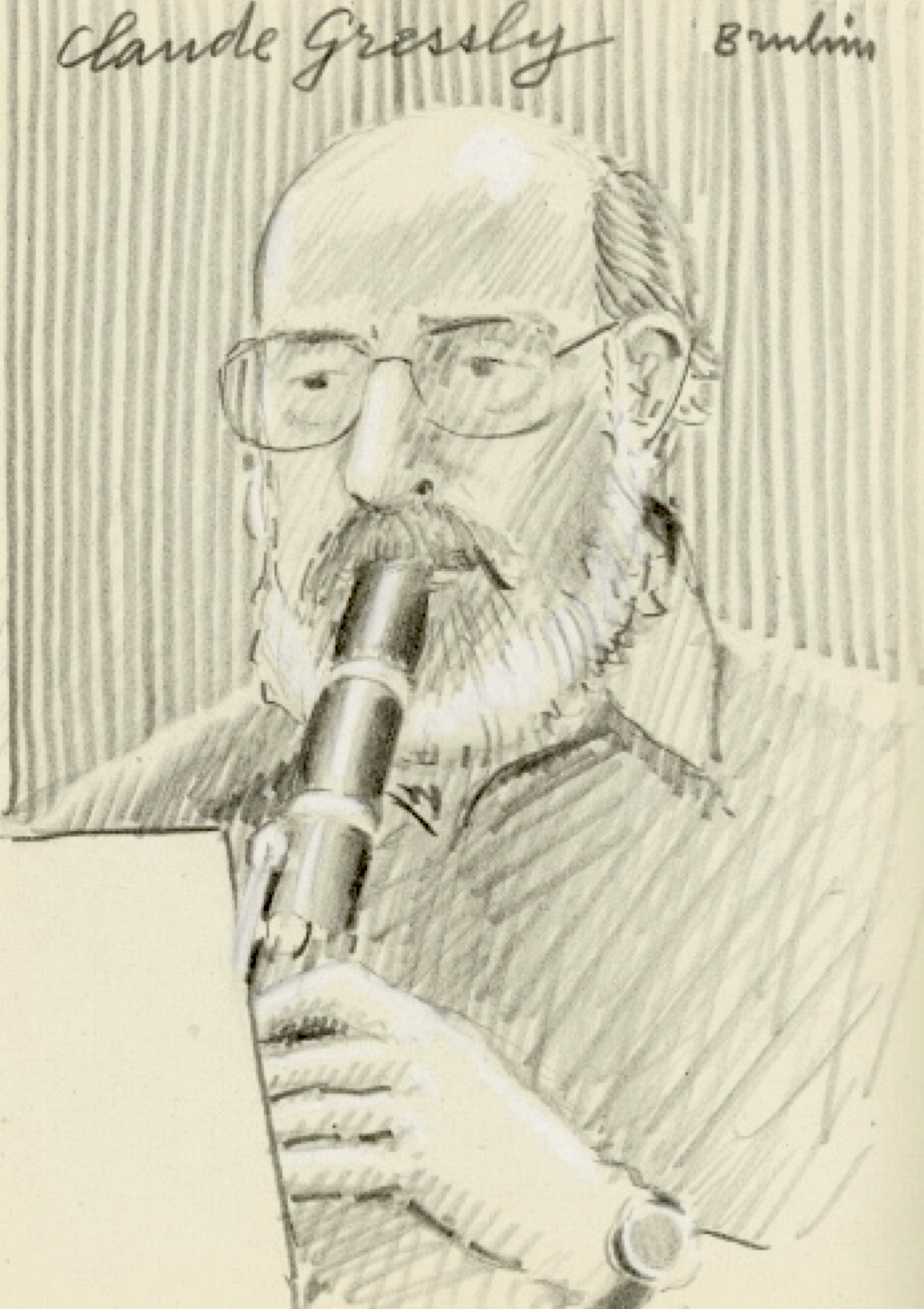

HUO: I see a drawing of Ländler [folk music from Austria, Switzerland, and Germany among other places] musicians on the wall here. We first met in the early ’90s, when we made this book with Kasper König about public art. Peter Fischli and David Weiss suggested that I include your Ländler musicians; and we ended up including several pages of them. I also first learned from Fischli/Weiss that you are a legend in the Ländlermusik world. How did it all begin with Ländlermusik?

AB: My father played the violin in the Tuggen church orchestra, as well as ad hoc for weddings and dances. I took violin lessons for about eighteen months and was able to play along on occasion. Later, Jimi Hendrix became more important to me, but I never scrapped the Ländler music. I didn’t practice it anymore, but when I heard a beautiful Ländler on the radio, I pressed record on the cassette player.

Later, I was advised to perform with my aging father again. So in the mid-eighties we resumed playing violin as a duo. We traveled around to different venues, and at some point, I found a cassette on the sale rack of a Migros checkout at Limmatplatz. It had both violin and trümpi on it, which had been rare in Swiss music since the Second World War. It was a real find. This older, deeply authentic Ländler—rarely heard, and even then only in a few remote valleys—just lying there, overlooked, at the checkout!

With my interest rekindled, I attended as many folk music concerts as I could—in and around Zurich, in the inner and outer canton of Schwyz, with excursions to Appenzell, the Basel area, and the Bernese Highlands. I wanted to get to know the literature so I could broaden my repertoire. I did this for a few years.

The music in pubs and halls usually lasted from early evening until midnight, often till two o’clock or later. What was I supposed to do with my hands that whole time? It made sense to start drawing the musicians. And anyway, they hunker at the front of the stage the whole evening, staying relatively still, so it was both pleasurable and practical. I drew with an H2 pencil in A5 books, on recycled paper with a dull chamois tone. Mostly I heightened the drawings with white wax chalk. Then, more and more, guests and musicians wanted to see the booklet. It was like a little dog that immediately becomes a conversation starter.

Eventually the trio Götterspass (Patrick Frey, Beat Schlatter, and Enzo Esposito) requested a poster in the style of these live portraits. So I drew them in the same sketchbook, but treated them a little differently, skewing more toward caricature than portrait. It made for a nice poster. That’s how I found acceptance in the scene.

HUO: We’re talking about portraits, and here in your studio, we’re surrounded by your portraits. It seems to me that the portrait has played an important role for you from the very start.

AB: When I took up painting in the late ’70s and early ’80s, right away I started with portraits—the most difficult discipline. That takes nerve. The self-portraits from 1981–83 were a good start, since I was always available as a model, and photographic likeness was not my primary concern. Self-portraits mainly served as a pretext for filling up a canvas.

In a classic portrait commission for a third party, however, photographic or perceived resemblance is at the fore. Put it this way: No sooner does a newborn see the blazing light of this world than the face and scent of the mother are indelibly imprinted. The recognition of faces, the registration of the slightest physiognomic movement, is rooted in our first instincts.

The same applies to the representation of automobiles, incidentally: the slightest deviation, and the image won’t turn out.

Portraiture is undoubtedly the most demanding genre of painting. It was an invigorating challenge for me. But it was good for me to be ambitious. After I overcame the hurdle of portraiture, landscapes and other subjects came more easily.

HUO: What would your advice be for young artists, musicians, poets, writers or Ländler musicians?

AB: This is not advice, I suppose, but a hint: In the beginning was the preface. Always start texts with the first letter, or music with the first note …

HUO: Have we forgotten anything?

AB: I had a great experience with rotomotor. In 1998 I played trümpi in a stage play in Tokyo. Before the performance, the whole rotomotor was played in the foyer, in the hall as it slowly filled, and in the artists’ dressing rooms. Nobody understood a word but me—but it still worked! Even people who didn’t understand the text played it and heard it and thought it was good. People in Japan know me from the noise scene, and they were surprised that I play trümpi, totally astonished.

HUO: Wow.

AB: I work across various disciplines, but they all come from one source. The impression of a colorful, unmanageable mixture may be confusing at first glance, but on closer inspection, it becomes clear that everything has the same esprit. They are connected—not through mimicry or masquerade, but through a straightforward shared philosophy of making: Content follows at the foot of form.

HUO: Could one use the term Gesamtkunstwerk?

AB: A somewhat overtaxed term, but definitely applicable here. At least, it doesn’t seem out of place.

HUO: Are you interested in bringing all these dimensions together, either in a book or an exhibition? So far it has always been very scattered, in a sort of anarchic underground logic. Has there ever been this kind of consolidation?

AB: That’s exactly what happened with the guys at the Hacienda gallery in Zurich; my music, my books and a cross-section of my visual works were exhibited.

HUO: One last subject: I’ve been told again and again about your Happenings. You held actions starting in the late ’60s, until, as you said, you withdrew in the ’90s.

AB: I devoted the ’90s primarily to the trümpi. Making art was on the back burner.

HUO: Peter Fischli told me about your actions in Bellevue. I want to know more about these Happenings. It sounds like almost a kind of Fluxus, like Emmett Williams.

AB: I was, without pressing the Fluxus button, always “Fluxable.” I “am” not Fluxus, but I have a connection to it. Fluxus is preceded by a long series of related innovations. Tomfoolery in the Middle Ages, Till Eulenspiegel, Hieronymus Bosch, Mannerism, Baroque literature, English nonsense, Karl Valentin, Dada, aspects of surrealism, Yves Klein; these “absurd” actions had been around for centuries. Then came Happenings and Fluxus, and I grew up with that in art school.

There was an open-air exhibition at Bellevue, where I showed ink drawings and did a thing with fire on the lawn. It was somewhere between a Happening and Land art. The first big Happening I did was in the late ’60s, early ’70s, in the Mattenhof gravel quarry. There was a circular runway for model airplanes there. I positioned five drummers around it and lit the circle on fire using sawdust and gasoline. There was just one small poster, a notice at a restaurant, but that was enough. An audience showed up, in any case.

On other occasions, I put up hectographed A6 flyers. At the time, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung came out three times a day, and the newspapers lay in open boxes, so I put a flyer in each one. Or on Thursdays, when the trash was out for collection, I stuck flyers on the garbage bags, even though they would disappear in half an hour. I’d attract attention with a small print run: information—with little loss.

HUO: Little loss. That’s the motto.

AB: Nolens volens. That’s how it happened.