Cover of the Attica Book, illustration by Antonio Frasconi.

Man I’m back again,

Why — — — ? Is it because I’m a society child that

Is not going to play your petty games with

Time and Freedom.

D. Cusic, “Man I’m Back Again,” Attica Book

In 1972, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), in partnership with the organization Artists and Writers Protest Against the War in Vietnam, published the culmination of their swift response to the September 1971 rebellion at Attica State Prison—the Attica Book. The publication featured black-and-white reproductions of works commissioned from forty-eight artists affiliated with these organizations and their allies. This robust set of ruminations on the event ranged from images of suffering and isolation (Vivian Browne, Mary Frank, and Benny Andrews) to sparse abstract works on paper (Irving Petlin and Jack Sonenberg) and clustered prints indicating bars, chains, and crowds (Melvin Edwards and Jacob Lawrence). One collage work by Rudolf Baranik makes use of the type of blurred aerial footage that suffused the media’s coverage of the rebellion. A collection of texts by incarcerated writers, mostly poems, was assembled in a separate section at the center of the volume. These writings had been produced in BECC’s Arts Exchange program—organized first at the Manhattan House of Detention just weeks after Attica—which hosted art and writing classes in prisons and jails across the state. 1 The practice of Arts Exchange and the publication of Attica Book sought to provide a forum for an artistic response to the uprising as a material gesture of support, by forging coalitions between artist organizations and between artists and incarcerated people.

Faith Ringgold, United States of Attica, as reproduced in the Attica Book, 1972.

The Attica Book

The book opens with the artist Faith Ringgold’s poster United States of Attica, 1972, a map of the U.S. populated with the artist’s small block lettering that gathers counter-histories of scaled violence, from small incidents at the county level (a 1936 strike in northwestern Arkansas, a KKK conspiracy in Philadelphia, Mississippi, in 1964) to world-historical events (the bombing of Nagasaki, the Korean War), into long lists written on states and in the map’s ocean areas. Dedicated to the men who struggled and died at Attica, Ringgold’s most widely distributed poster places the uprising in the context of five hundred years of American counterrevolution, urging the viewer to write in “whatever you find lacking,” foreseeing that even its own detailed compilation would inevitably be incomplete. Placing Attica at the center as the inheritor of the work’s alternative historical survey, United States of Attica frames legacies of racialized confinement and resistance, from Wounded Knee to Vietnam, as the true background of the uprising. In turn, Attica Book contextualizes its own intervention by beginning with Ringgold’s poster, memorializing the dead and elucidating its own coalitional politics as part of a long and varied history of opposition.

Upon closer inspection, the history of postwar art in America contains a similar counternarrative if we begin with Attica and the art marshaled in response to it. In his preface to the book, artist and BECC leader Benny Andrews emphasizes the publication’s formal heterogeneity, its “wide stylistic spectrum, from expressionist outcry to laconic conceptual incision.” 2 The opposition he invokes, between the figurative expressionism of his own practice and experiments in dematerialization of other contributors, is pointed—responding to the institutional galvanization of minimalism, conceptualism, and performance, and their artificial segregation from more traditional media, particularly painting. In many ways the Attica Book can be considered a rejoinder to the BECC’s own boycott of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s “Contemporary Black Artists in America” exhibition in Spring 1971, which began as a protest about black representation within museum leadership and became a story about a false division between politically engaged painting (by Andrews and Vincent Smith) and abstract, formally innovative, and supposedly autonomous work. 3 Instead, the Attica Book proposed a united artistic front—decisively in opposition to segregation by form or style—around a driving purpose, which in this case meant memorializing the uprising in as many different idioms as possible and raising money through book sales for the BECC’s arts in prison programs. In Andrew’s words, the Attica Book was “a collage of indignation, witnessing the communality of America’s artists speaking for a shared truth,” a communality that transcended the kinds of institutional divisions then involved in defining, in particular, the parameters of minimal and conceptual art. 4 In a 1973 letter to Artforum— written in response to MoMA refusing to sell the Attica Book in its bookstore—Andrews, Baranik, Petlin, and BECC co-chair Cliff Joseph went so far as to define the volume as a periodizing statement on art of the time, an “art event as well as a statement of conscience,” which unified contemporary art circa 1971 in its full formal breadth and orientation toward the era’s pressing social crises, from Attica to Mỹ Lai. 5

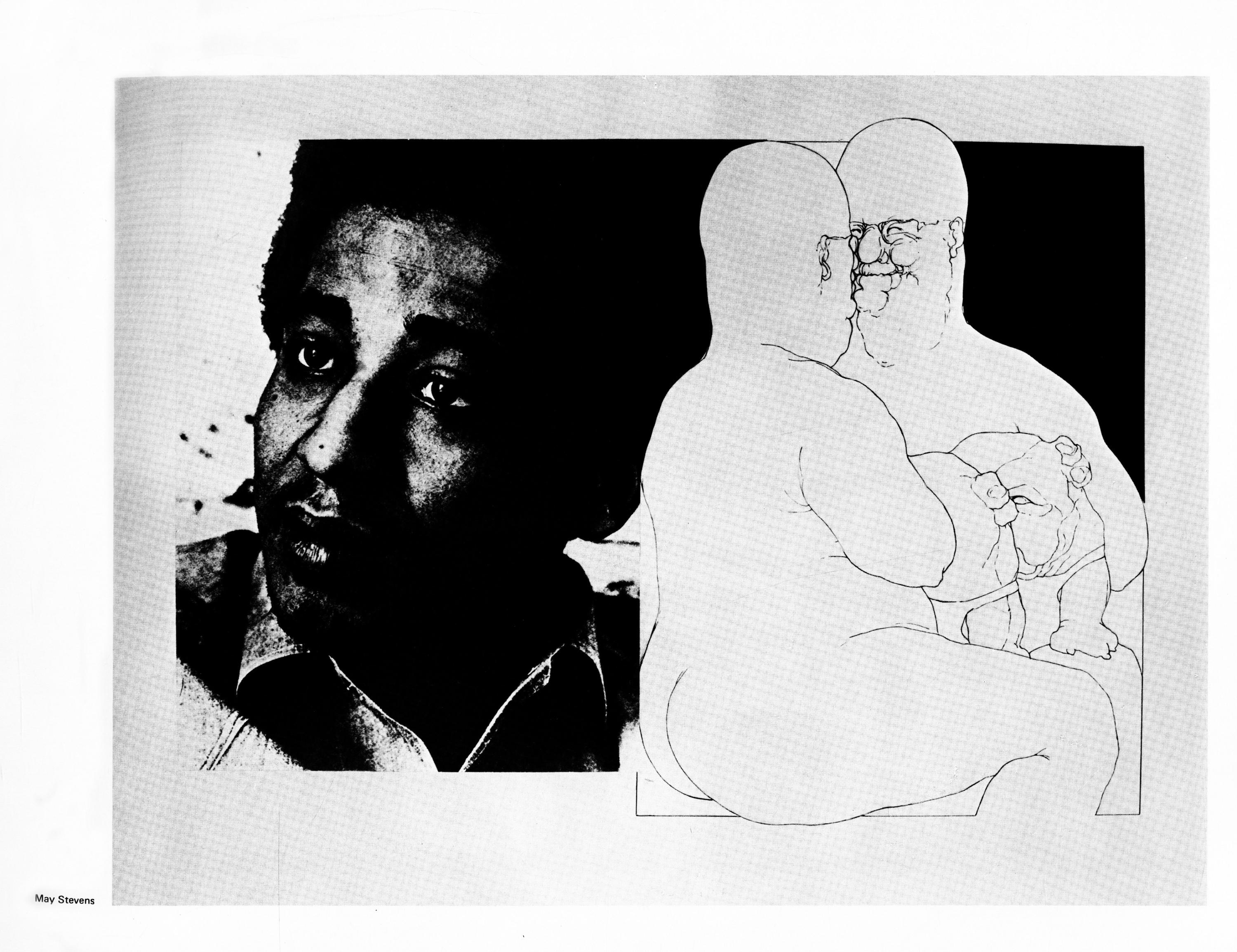

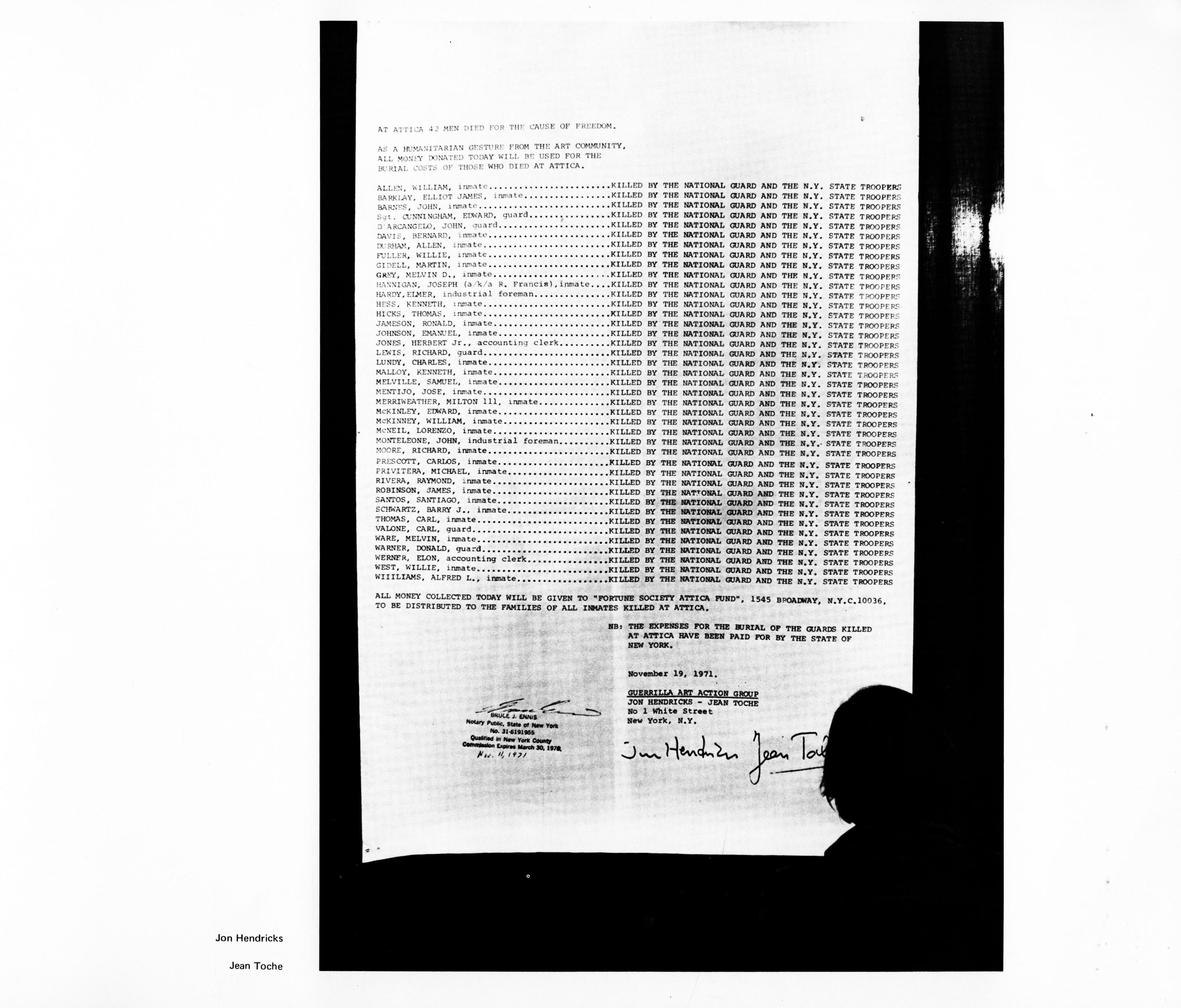

Attica Book’s “collage of indignation” did not posit formal difference as inconsequential, however. Instead, it sought to show, through a tight succession of grainy reproductions, how contrasting media offered distinct capacities within the project’s overarching response to the massacre. Works by Alice Neel and Bette Lang memorializing unknown prisoners in solemn portraits contrasted with John Dobbs’s effigies of cops and Patricia Mainardi’s sinister portrait of Rockefeller. Some contributions paid tribute to specific visionaries, such as a strange collage for George Jackson by May Stevens, which overlaid a photograph of the revolutionary with a pencil sketch of a nude, round white man facing his own reflection. The Guerilla Art Action Group (Jon Hendricks and Jean Toche) presented a characteristically conceptual piece: they produced a document, stamped by a New York State notary, which listed the names of the imprisoned men who had died at Attica. Requesting money for their burial expenses, which went to the Fortune Society’s Attica Fund, the work reminds readers that the state had already covered funeral costs for families of the murdered guards. The conceit of the Attica Book is that the bloom of new art practices in the 1960s and ’70s—from “expressionist outcry to conceptual incision”—provided an arsenal useful for responding to Attica as a layered crisis, not only the events of September 9–13, 1971, but the expansion of the prison at large. 6

Scene from a Mobilization for Youth coffee house storefront, 1962. MFY News Bulletin, Fall 1963, Vol 1. No 2, Henry Street Settlement Records, Social Welfare History Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries. Courtesy Henry Street Settlement.

Attica’s Foundations: Art, Welfare, and the Carceral State

This real capacity to confront the crisis however, exemplified by the Attica Book and the BECC’s tangible efforts on the ground in New York’s prisons and jails, was inseparable from art’s actual involvement in carceral expansion. A decade before the Attica rebellion, in the early 1960s, the last robust welfare program in the U.S., the “War on Poverty,” began to corral subjects for innovative forms of penal processing. The extensive cultural programming that acted as a draw to these new forms of social spending was integrated with, and oftentimes executed by, artists and musicians already known to histories of advanced art in the early-to-mid 1960s. Specifically, welfare programs mimicked the social forms of various avant-garde institutions—coffee houses, Beat cafes, jazz outposts—as a way of integrating into Lower Manhattan and Harlem, key sites of cultural activity that were crowded with some of the poorest communities in the country.

The exchange was understandable. These welfare programs funded things like the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School (BART/S), the Puerto Rican Traveling Theater, and dances by choreographers such as Percival Borde and Pearl Primus. They installed temporary public sculpture by Judson-affiliated artists Peter Forakis and Mark di Suvero, and murals by the color field painter Betty Blayton. Spearheaded by the poet and playwright Amiri Baraka and the writer Larry Neal, the BART/S in particular organized a rich swath of events and exhibitions in its short life span, showcasing several artists included in the Attica Book, such as Romare Bearden and the painter Vincent DaCosta Smith. The BART/S used its federal money for parades down 125th Street led by Sun Ra and Albert Ayler’s quartet, and collaborations with musicians including Milford Graves and Giuseppi Logan, Ornette Coleman, Pharoah Sanders, Marion Brown, J.C. Moses, and many others. 7 In turn, the shows led people to the state programs to which these organizations were attached. The Attica Book is one product of this largely untold history, evident in its view of a manifold contemporary art, the politics of its collectivity (and the connections between artists forged by these institutions), and its precondition for existing (exploding prison populations and the dire conditions that attended them). The BECC’s Arts Exchange was initially funded by the New York State Council on the Arts, a Rockefeller initiative and product of the cultural policy that bloomed during the War on Poverty era.

Advanced art’s particular intimacy with the carceral in this era, whether in opposition to it or as its unwitting handmaiden, is the subject of this text, which aims to rearticulate the emergence of minimalism within the historical conjuncture that produced the Attica Book. In the early 1960s, minimal structures repeatedly invoked the experience of confinement and made the prison a motif, effectively registering the expansion of incarceration into civil society and everyday life for specific groups of people. For a clear image of the genre’s driving interest in control, think of Robert Morris’s claustrophobic Passageway, 1961, and with it, the viewer’s confrontation, and therefore potential transgression of, her own impounding. Minimalism’s uncanny ability to describe the experience of enclosure, is due, in part, to its inhabitation of the same space and time as a critical moment of carceral invention (Lower Manhattan in the early 1960s), and, in a material sense, its overlap with this activity. 8

While the federal War on Poverty briefly reduced the poverty rate to its lowest level since records began, it also created a new bureaucratic infrastructure that fused social welfare and policing. 9 The War on Poverty saw an unprecedented infusion of federal funds into what were essentially NGOs (namely, publicly funded organizations governed by appointed experts) placed strategically in communities undergoing divestment, from historically agricultural and mining areas to former industrial urban cores, such as Lower Manhattan. New York City, the so called “laboratory” for the War on Poverty’s “new social welfare” experiments, was the location of the very first programs of this kind prior to their national rollout in 1964. An early anti-poverty organization, Mobilization for Youth (MFY), opened on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1962. Its programs—developed with area artists, social workers, and a team of social scientists affiliated with Columbia University—served as blueprints for national War on Poverty programs through the early 1970s. It was entwined with Lower Manhattan’s art system, and utilized it—its rhetoric, social spaces, agents, and emergent art forms—to procure the participation of its target demographic: poor black and Puerto Rican teenagers and their families.

The intersecting social processes that justified MFY’s intervention in the neighborhood also seeded the carceral crisis that bloomed into the conditions the Attica Liberation Front confronted roughly a decade later. These are the well-trod social coordinates uniting postwar industrial restructuring with automation and its attendant demographic change that are largely omitted in histories of art of this period. 10 MFY’s service area was produced by the decline of light industry in Lower Manhattan since the late 1940s, when the small factories that had once employed its population began shutting down. These closures dovetailed with increased migration from the U.S. South and the Caribbean caused by shifts away from traditional farming labor in both regions. 11 Migrant populations of black and brown economic refugees in formerly industrial cities were the War on Poverty’s primary object and source of anxiety over the political uprisings that came to pass later in the decade, during the so-called “hot summers” of the mid-to-late 1960s. These rebellions, from Harlem in 1964 (the same year Johnson declared a “war on poverty”) to Watts in 1965, and Chicago in 1966 (as well as a host of underrecognized uprisings including those in Tampa, Cincinnati, and Atlanta, all in 1967) drove but also changed the course of the poverty war, thoroughly reorienting it around social control. 12 Earlier, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, black and Puerto Rican workers in these areas, excluded from what was left of unionized employment in the construction trades, for example, and meagerly supported by the poor quality of existing social services (when they weren’t outright withheld) administered by discriminatory Irish- and Italian-American political machines in city government, withstood acute immiseration. This scene was intensified by general divestment from former industrial areas at the municipal and state levels: depleting school resources, housing stock, and public health facilities.

The historian Elizabeth Hinton’s book on the War on Poverty effectively illustrates how mass incarceration developed out of the War’s new infrastructures of “patrol, surveillance and confinement.” 13 Programs like MFY provided novel pathways for the state to enter into segregated and impoverished areas, increasing its overall capacity for surveillance—in number of sites and scope—giving police and the federal government “new channels of supervision” over marginalized communities, and setting policy precedent for the swelling of parole and probation infrastructure throughout the 1970s and ’80s. 14 Both major anti-poverty organizations in NYC (MFY in Lower Manhattan, and HARYOU-ACT in Harlem) opened youth centers, drug rehabilitation centers, and legal and social service clinics, which at times partnered with law enforcement. In this way, needed social services were bound to repressive institutions that referred people for arrest and rehabilitated the image of the police—setting up summer sports games between officers and local children, for example. 15 The entire infrastructure of the poverty war created new cartographies of race, poverty, and assumed criminality, literally drawing incredibly detailed, block-by-block boundaries around their “service areas,” which were patrolled with renewed purpose and attention. 16 These extended methods of penalization outside the prison accelerated mass incarceration and laid the groundwork for the more well-known welfare to prison pipeline today. 17

MFY’s Community Relations Division for example worked extensively with the New York Police Department’s Ninth Precinct (located on Fifth Street and Second Avenue) to develop a slew of “police–community relations” initiatives, which included lectures and discussion groups between police and neighborhood residents. 18 One proposed program included the opening of a “little station house” in a neighborhood storefront that would provide “a more informal and less overwhelming environment for interaction between the police and local citizens.” 19 It is this kind of granular programming that invigorated exchange between an evolving and expanding carceral state and the poor. It is worth noting that, like any complex reform operation, MFY had radical strains and struggled under the weight of its central contradiction—offering its constituents emancipatory tools, art among them, while advancing an apparatus of social control. Dissident social workers and artists in the program collaborated with area residents on rent strikes and school boycotts and redirected federal resources towards grassroots leadership whenever they could. The activist group Mobilization for Mothers, which publicly agitated to win more resources for Lower East Side Schools, and for their desegregation, was formed in MFY’s storefronts, and is considered a precedent for the welfare rights movement. 20 The poet Hettie Cohen, Amiri Baraka’s first wife, was among MFY’s employees, as were the dancer Rod Rodgers, the filmmaker Roberta Hodes, and likely many others who remain uncredited in the program’s archives.

MFY’s art and culture program sought a collaboration with the poor that, like the BECC’s later Prison Exchange Program, placed art as a figure of liberation in dialectic with control. In the case of the BECC, the group had to abide by corrections policy benchmarks in order to offer art and writing programs in prisons and jails throughout the state, feeding into debate about the management of the rising prison population. 21 This was a compromise it knowingly accepted in order to offer self-expression as a tool of emancipation. Throughout the decade prior, MFY’s arts program emerged from the Black Arts Movement’s commitment to radical pedagogy, which the playwright Woodie King Jr. (director of MFY Cultural Arts division) discussed as the Movement’s largely unrecognized foundation. 22

The organization trained legions of young artists, filmmakers, writers, and dancers. Yet it also facilitated what can only be described as art-led surveillance and enclosure of targeted groups. For example, MFY ran a “coffee house” program that mimicked the bohemian outposts then flooding the East Village from the West and the Tenth Street artist colony just to the north. Bucking welfare tradition, the coffeehouses provided “a new kind of space for youth in trouble, symbolic of the style and mood” of the area. 23 Press releases emphasized the area’s bohemia directly: “one imaginative program involves the cooperative establishment—with area teenagers—of cool and jazzy area Coffee Shops”. 24 One coffeehouse instituted a “Spanish ‘Living Theater’ workshop,” and social workers posing as “informed bartenders” served pop behind its makeshift bar. 25 Such references to the Living Theater, which, in 1962, operated out of a nearby Union Square theater space, and the coffeehouses serving Lower Manhattan’s art world, underscore the utility of advanced art for MFY’s reinvention of welfare procedure. 26

In these coffeehouses teenagers formed bands and put on plays, but perhaps most importantly they hung around and spent time under the watchful eye of MFY social workers. It was the long duration afforded by art’s social autonomy, specifically the collapse between work and life that afforded extended hours in coffee shops and institutions, including the nearby Cedar Tavern and the Five Spot, which proved a useful model for MFY’s honing of an innovative medium for supervision. This medium—from the “little precinct” to its coffee houses—created new kinds of space and extended time for interaction between community members and state agents, whether actual police or social workers. I am not so much positing a causal or quantitative relationship here, particularly between any of these individual actors, so much as I am noting how uniquely facilitating the social institutions of advanced art were—in their radically extended timeframes and informal, socially generative spaces—to the kinds of surveillance and supervision practiced at MFY. It is striking how much more time and conversation—interactions between people and the state—the coffeehouses would have offered in contrast to the forced dialogue format at the “little precinct” or the delimited hours of a baseball game.

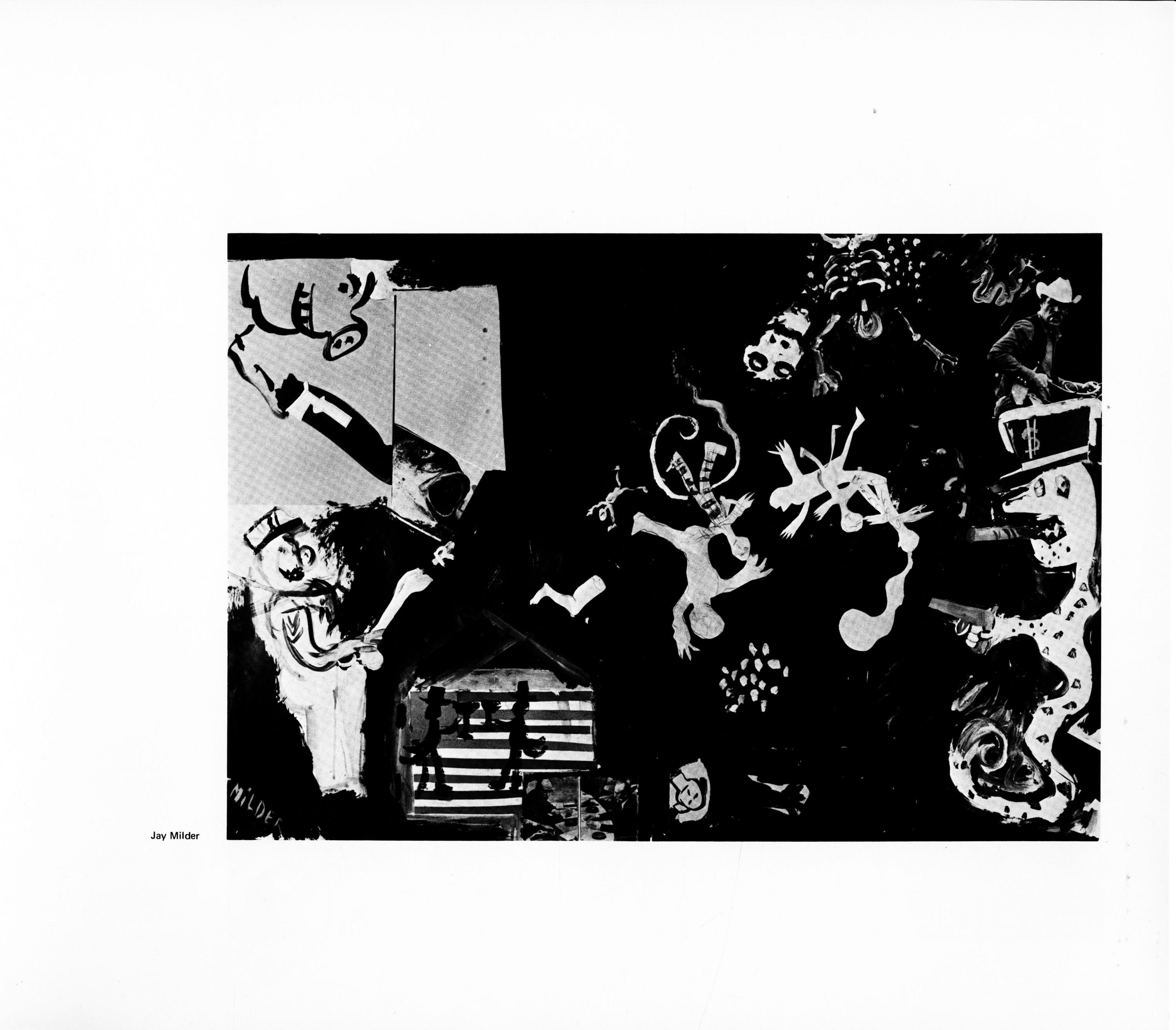

That one artist who worked for MFY, the painter Jay Milder, later contributed to the Attica Book, empirically testifies to the short circuits between Lower Manhattan’s art system and federal anti-poverty work and offers a case study of carceral technique after 1960. Milder was a painting instructor within MFY’s Cultural Arts division where I’m sure his teaching was well intentioned, if not meaningful. Without speculating about the motivations of particular individuals, this linkage allows an alternate reading of the Attica Books’s art, not only in relation to the uprising but to the broad expansion of the prison system tangible by 1971.

Milder’s collage-painting combines muddy profiles of cops, cowboys, and politicians with their photographic correlatives, cut from cigarette ads and newspaper reports of official proceedings (the clip at the bottom center left is likely a hearing relevant to Attica, but the reproduction is too small and grainy to identify). Surface texture—opaque planes of rich black, sections of congealed paint, and papery dry corners—fasten a scene of chaotic bodily action. The prevalence of limb-like shapes—bent legs and femur bones, outstretched arms, a pointed gun, a stiff cigar—generate the sense of quickened movement in a dark space. Violence is repeatedly presented and revoked. It is clear in the gun, in the invocation of a group beating, and then suspended in the cyclical marks that indicate a celestial world, a surrealist fish, and icons of masks or heads that transcend straightforward narration of the uprising. This rumination on the problematic of representing the actual events of the occupation’s four days—in time, appearance, and historical construction—constitute Milder’s contribution.

Concomitantly, the work’s most bloated profiles—an evil pig, police officers armed with bones, toasting cowboys behind uneven bars—chafe against the artist’s role within MFY’s punitive function. Milder was in the Rhino Horn Group with Andrews, a group of “figurative expressionist” painters who remained committed to realism as Left societal denunciation. 27 Recalling the BECC’s Whitney protest, the problem with this kind of realism, perhaps, was less an idea about its retrograde approach and more its futility when responding to the actual dynamics of social capture circa 1971. Milder’s caricatures suggest that penal structure appeared as direct repression, when it was rather the daily march of supervisory protocols—fanned out into the world—that created the crowded conditions at Attica. In contrast to the trope of state violence offered in Milder’s contribution to the book, minimalist structures evinced a new, unitary capacity to index the experience of carceral expansion and contend with the proximity of art and state evident in MFY’s history.

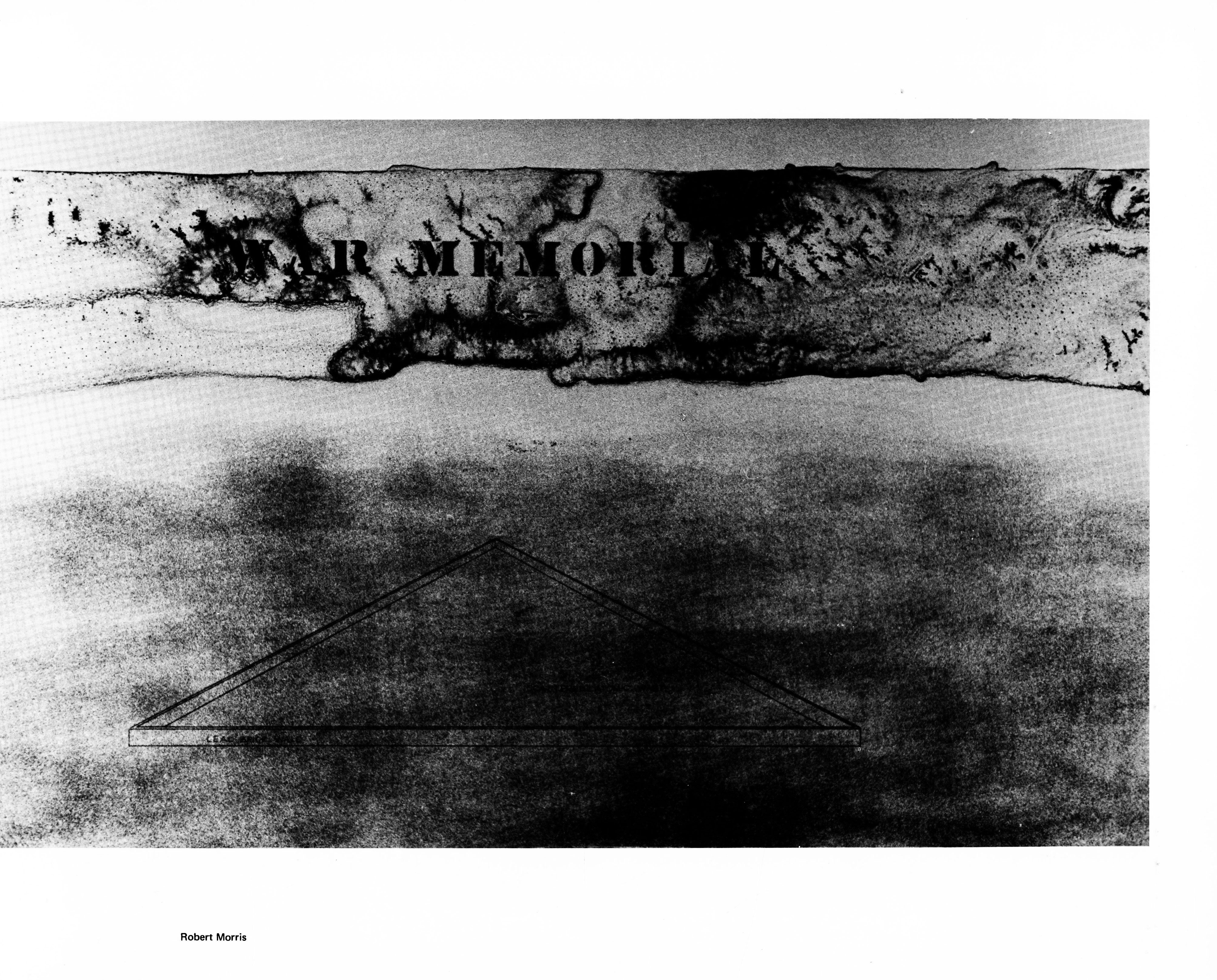

Robert Morris, untitled contribution to the Attica Book, undated.

Carceral Minimalism

The minimalist structure famously inaugurated a form of embodied viewership— “theatrical” in Michael Fried’s parlance, phenomenological in Robert Morris’s—or a viewership which placed the emphasis on the spectator’s literal time, space, and body in relation to a contentless form. 28 According to an influential reading by Anna Chave, minimalist sculpture’s engagement of the spectator was forged through its penchant for domination, exemplified in works such as Tony Smith’s imposing Die, 1962, and Richard Serra’s work more generally— artistic responses to the “brutality” of the decade (Vietnam, Watts, etc.). The genre has also been critically interpreted as engaging the subjective experience of social control in capitalism through the regimentation of time. 29 In this vein, many works—in the early 1960s, alongside MFY as well as in the decades later—reflect on imprisonment directly. Morris’s prototypical Box with the Sound of its Own Making, 1961, in which a metallic construction soundtrack emanates from a mute cube that is closed on all sides, thematized internment and acted out the construction of circumscription and isolation in real time. The critic Carter Ratcliff’s minor interpretation of the work takes on new significance in light of the alternate history at issue here. He wrote: “the thoroughness with which the recording is boxed in joins with the isolated persistence of its sound to symbolize an escape proof situation.” 30 Ratcliff also termed Morris’s “reductive modernism” an “imprisoned art” and Morris the “administrator of confining possibilities.” 31 Certainly this is a subsidiary history of minimalism, but a persistent one nonetheless, which takes on new significance in light of the Attica Book’s instigation of an alternate history. Other minimalist approaches to confinement in this period include Simone Forti’s series of dance constructions modeled on caged animals in the late 1960s, based on fieldwork at the Rome zoo and “dedicated to understanding captivity,” Morris’s devastating mesh cage from 1967, and Bruce Nauman’s “Corridor” ongoing series, begun in 1967. 32 Thematically, there are Yvonne Rainer’s Film About a Woman Who . . . (1974), which pivots on a scene about Angela Davis’s love letters to an imprisoned George Jackson, Serra’s video piece Prisoner’s Dilemma, 1974, and Anna Halprin’s production New Time Shuffle at Soledad State Prison in 1970. In the later ’70s and ’80s, that which had been left oblique previously was being named in works such as Morris’s In the Realm of the Carceral, 1978, a group of black ink drawings, and Peter Halley’s Apartment House/Prison, 1981, a series of paintings showing cells and conduit systems, which the artist described as a counterpoint to Judd’s work and that of others from that earlier generation. 33 Tony Conrad’s Women in Prison, 1982–83, which reflects on the trope of incarceration in popular cinema, began with the installation of a prison cell replica in his studio. Mike Kelley and Tony Oursler occupied the cell as actors in an unfinished “jail movie” filmed over some six hours. 34 In a sense, Women in Prison proposes the penitentiary as an inevitable point of inquiry for the experiments in immersive experience that characterize Conrad’s earlier career with the Theater of Eternal Music/the Dream Syndicate, such as La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s “eternal” sound and light installation the Dream House, 1969–.

Presiding critical explanations for this kind of practice rest on the idea that they reflect the economic restructuring attendant to this period, and usually train their attention only on white-collar work. Many of these works (not all) have been usefully explained by “deskilling,” a process of artistic simplification (sometimes taking the form of outsourcing or delegation) that has been likened to automation. Other arguments have understood conceptualism in particular as furthering an aesthetic of “administration” in line with the rise of management and service-based work. What I am proposing here—what Attica Book requests—is a history from the underside which connects the art of this period with the surplus populations generated by this same industrial change. Accordingly, those imprisoned are another referent of the art of this period, and the prison is a sector of society that intersects with it alongside management, real estate, and the various markets associated with art.

The question—and it is a wholly speculative proposition; a conjecture, even—becomes whether MFY learned to deploy time not only from the social world of advanced art (downtown coffeehouses), but from its most advanced practitioners as well. MFY was a hinge between duration as a mode of carcerality (including surveillance and custodianship), the social world of advanced art, and, perhaps, experimentation with an emphasis on extended spectatorship in the artwork of this period. As we have seen, MFY glossed Lower Manhattan’s avant-garde quite generally: the loose group caught in its policy language potentially included anyone associated with downtown. I am going to interpret MFY’s reference to the Living Theater, however, as functionally (if not consciously) a citation of a broader artistic avant-garde that expanded the possible sites and temporalities in which art could take place. 35 For example, the cohort around the Living Theater’s post-theatrical practice—which included Morris, John Cage, and Andy Warhol—was one devoted to innovating the parameters of aesthetic experience through duration; an idea that has appeared in criticism of this milieu since its inception. In 1967, Michael Fried lamented that the period’s intermedia experiments generated “a mundane spatial expanse, with no discernable bounds, which continued for an ‘endless or indefinite duration.’” 36 That this “indefinite” time was also being generated at MFY would be a merely parallel observation if not for the organization’s express citation of advanced art in its programmatic structure. Minimalism’s early replication of unnamed, indirect, and omnipresent forms of control—and later, its more direct emphasis on the prison—is given a new history through the story of its emergence from MFY’s site and period. In this narration, minimal structures furnish an immanent critique of the prison as permeating the world, and are equipped with this special ability through the genre’s early historical exchange with MFY’s history.

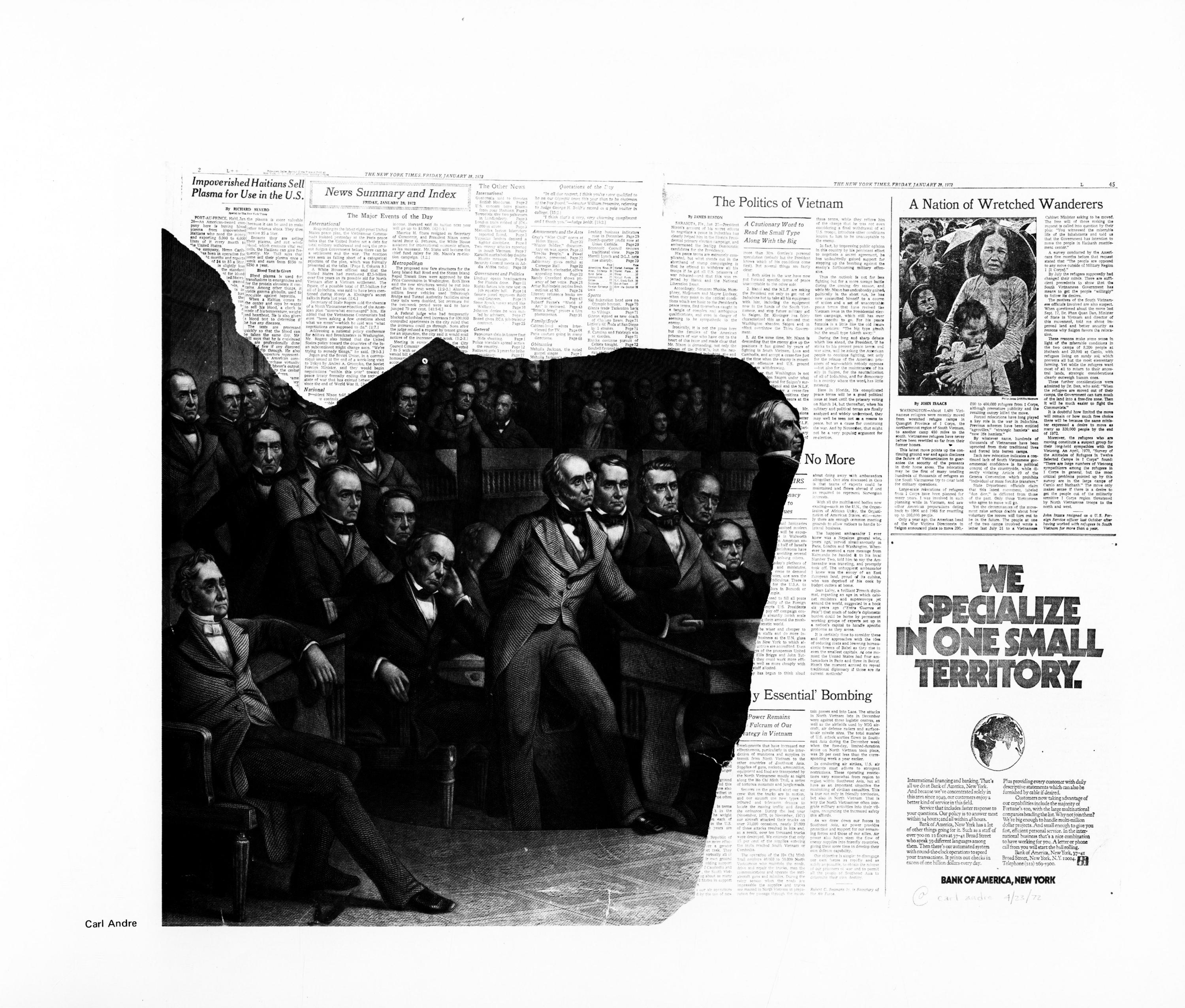

Interestingly, the Attica Book contributors most associated with minimalism, Morris and Carl Andre, did not contribute minimalist specimens. Rather, they both used the parameters of what has been usefully termed a “reductive modernism” (in contradistinction to Milder’s expressionism) to connect the events at Attica to broader features of U.S. imperialism. Andre created an uncharacteristic collage, in marked contrast to the floor sculptures of standard construction units for which he was becoming well known in the early 1970s. The central image is a ripped section of the Robert Whitechurch print The United States Senate, A.D. 1850, 1855, that commemorated the Senate hearing on the Compromise of 1850, passed that year to quell tensions between slave and free states in the Western territories. Under the Compromise, slavery was abolished in Washington D.C. and California was established as a free state, but the Fugitive Slave Act was passed, providing recourse for the legal recapture of escaped people regardless of the legality of slavery in the state. Andre excised the print’s central action, Kentucky statesman Henry Clay arguing in favor of the Compromise, and focuses attention on the body language of the senator spectators, their authoritative contemplation. This section is placed over a single newspaper page, juxtaposing the senatorial postures with articles on bombings in Vietnam, starvation in Haiti, and a Bank of America ad, which announces its territory as the entire globe. The collage roughly layers found print materials in the manner of the simply laid bricks of works like Equivalent V, 1969, suggesting a critique of mass media alongside the clear linkage between war, the global financial system, and its origins in the forcible acquisition of land. Andre’s conceptual argumentation foregrounds corporate frontiership as the contemporary inheritance of the Fugitive Slave Act. In one reading, the work privileges the acquisition of territory over the racialization of labor in the history of American capitalism; in another, it proposes slavery as the basis of global U.S. reach and landed order.

Morris’s lithograph, on the other hand, features a banner of foreboding ink wash swarming the top third of the page. Its topographical surface cuts against the larger static background, its texture reading as cloud, land, or ocean floor. Over this wavering banner is stamped: war memorial. The print is part of the “War Memorial Portfolio,” an understudied series comprised of similar prints addressing nuclear waste and chemical weapons. Suspended in the space below is a finely drawn triangle, its tip pointing away from the viewer. The shape has a slight depth, like a monument cut into and resting in land, prefiguring Maya Lin’s sharply forked Vietnam Veterans Memorial by a decade. Its three-dimensionality is slight, maybe a few inches deep. The study is reminiscent of much of Morris’s production from around this period, such as the trigonal labyrinth structures forcing participant-viewers into their sharp tips. This model, however, specifies what it memorializes. Inside the shape, in small, stamped letters that nearly recede from view: scattered atomic waste. On its outside wall, at the left corner: lead brick wale, referring to a raised ridge of a nautical vessel, a horizontal support used for internal bracing in construction and excavation, and to skin welts formed by lashing. The latter phrase triangulates the labor of building, to the ship and the whip. Forced migration and labor—slavery—are bound with contemporary violence, domestic and imperial. Like other works in the book, Morris’s drawing asserts the undeniable connection of Attica and Vietnam as interior and exterior manifestations of the same state brutality. He asks when the American war started, contending that it began in the Middle Passage, against those in the hold of the ship, their shivery space held together by a wale.

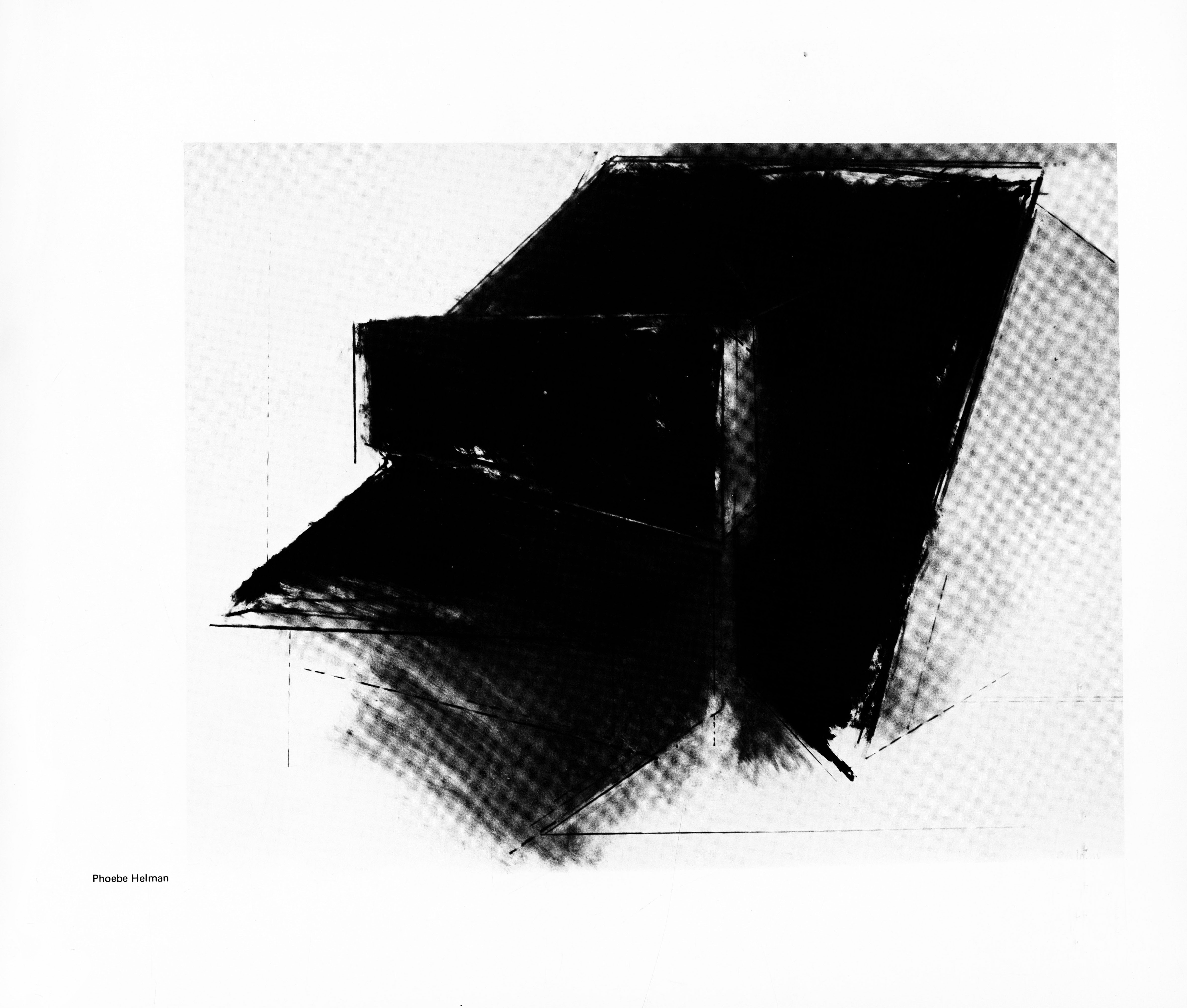

Phoebe Helman, untitled contribution to the Attica Book, undated.

“To prisoner poets and writers:” Attica Book’s collaboration

As we have seen, the art of this period fed carceral experimentation. In turn, a decade later the Attica Book made use of minimalism’s blank gestalt, propelling its particular capabilities—around presence and the overlapping structures of social and material phenomena—toward new critical genealogies. Attica Book’s united front, Andrews’s “collage of indignation” in its multivalent antagonism, also allowed the brute minimal form to place itself in tense conversation with Attica. I end with a work by the artist Phoebe Helman, which attests to the forceful capacity of minimal form to speak to carceral experience, an ability that I have tried to show was forged in the specific historical moment of their overlap. The drawing is in charcoal or black oil pastel over pencil, showing a hulking monolith cut with several angular sides. Its front quadrangle serves as an unsettling foyer into the larger death star. The ground beneath the edifice evaporates, however, as the lines that delineate its cubistic body exit into the thin space beneath it. It has no feasible foundation, its threat empty. A drawing, not a model, the sketch exaggerates the penal architecture of realized works of minimal sculpture, offering instead a dramatization of the prison which is more allegory than perceptual trick (contra Morris’s corridors and labyrinths.) The piece can be used as an illustration of Attica survivors’ descriptions of their environment:

Attica Prison—walls 30 feet high, 2 feet thick, 12 feet into the ground. Attica—guntowered and gated. Attica—where barred cubicles 6′×9′×7′ press down heavy upon the bodies and souls of men forced, like beasts, to pace the floors of this nation’s hidden concentration camps. 37

Helman’s cavernous complex contains these images, offering the approximation of such brutal measurements in place of anguished figures or historical extracts. The reliance on content in Andre’s collaged material and Morris’s use of text, betray an uneasy sense of solidarity with Attica, in their anxious labeling of an anti-carceral stance. In doing so, they shied away from minimalism’s intimacy with incarceration, instead securely marking correct, historically critical, analyses of the crisis. For two artists who generally made work of indeterminate, often contradictory meaning, their contributions are notably pointed. By contrast, Helman’s structure silently presents a hovering cavern, its blockish volume a testament to how form bears on the mind and body; its weight remembered like the gates, gun towers, and barred cubicles recounted by Attica’s inmates. In this, Helman’s drawing frankly presents minimalism’s specific ability to represent prison as too multidimensional, too accurate, to retain a comfortable distance or sense of critical separation. Instead, the drawing announces, and uses, the form’s involvement with prison (as architectural site, phenomenological metaphor, and horrendous lore) to present a compacted, resonant image of incarceration, perhaps as a realization of a caged perspective, the point of view of one entering its jaws. The Attica Book sets Helman’s drawing beside writings by Attica prisoners, a formal correspondence that encapsulates the book’s attempt to depart from the policy strictures of organizations like MFY and its offshoots in the 1970s and ’80s. While the BECC was a product of this history, it accepted its own complicity in order to produce another role for art vis-à-vis prison: as a formidable partner in the politics of its representation.